Three intriguing findings about pleasure and happiness

As someone who recently wrote a book reviewing all of psychology (Psych—now in paperback!), I hear from a lot of people who think my field is bullshit.

Sometimes, the skeptics don’t know much about the kind of research psychologists do. They reject psychology because of something they heard from an internet guru like Andrew Tate or because they had a bad experience with a psychiatrist. Sometimes, their skepticism has a religious source; they are convinced that everything worth knowing about the mind is already in the Bible, the Talmud, or the Koran.

But sometimes, the skeptics know a lot about psychology. They may believe that the replication crisis shows that you can’t trust anything that comes out of a psychology lab, that traditional psychological research has been superseded by neuroscience or computational modeling, or that the humanities provide us with a richer understanding of how the mind works. These are concerns worth taking seriously.

Still, I’m bullish on psychology and psychological research. In my post Psychology is OK, I list ten robust findings that psychologists have discovered (or at least substantially built upon) in the last few decades, most of which are of interest to non-specialists. Here they are again.

Babies have a surprisingly sophisticated understanding of the physical and social world before their first birthday.

Our conscious experience of the world is sharply limited; if our attention is elsewhere, we often fail to see what’s right in front of our noses. Check out this classic demo.

Memory is not an accurate recording, and despite what many of us think, our recollection of the past is highly distorted. False memories are not difficult to implant, and if you think you have an accurate memory of something that happened a year ago, you are almost certainly wrong.

Perception is a complex inferential process; what you see is influenced by your unconscious expectations of how the world works. As a vivid example, developed by Edward Abelson, B looks lighter than A because it’s in shadow, we have an unconscious assumption that shadows darken objects, so the mind “corrects” for the extra darkness. If you cover up the rest of the scene, isolating the two squares, you’ll see that A and B are the same color.

All sorts of psychological traits are heritable to a strong degree—not just the obvious ones, such as intelligence, but also surprising ones, like how religious you are.

Many sex differences are culture-specific, but others, such as differences in desire for sexual variety, are universal, showing up everywhere in the world.

We overestimate the likelihood of infrequent but conspicuous events, such as plane crashes and shark attacks.

There is a universal list of things and experiences that frighten people regardless of where they have been raised, such as snakes, spiders, darkness, and heights. This suggests that our fears have been shaped by natural selection.

There are universal features of physical attractiveness—such as facial symmetry—and even babies prefer to look at faces with these features.

Studies of people from dozens of different countries find that, as we pass middle age, we get more agreeable, more conscientious, and less neurotic.

I want to continue this theme here and give concrete examples of psychological studies that impress me and that I hope will impress you. I’ll zoom in on three papers on happiness and pleasure—a topic everyone is interested in. After reading about these findings, you’ll be bullish about psychology too.

1.

George Loewenstein, “Anticipation and the Valuation of Delayed Consumption,” Economic Journal 97 (1987): 666–84.

This is a technical article with math that goes over my head, but the idea is clever, and the findings are neat.1

Suppose you could kiss your favorite movie star. You could do it only once, but it could be any time you wanted. Would you pay more to get the kiss right away instead of waiting a bit? If you would pay more to wait, when is the optimal time?

When should you want the kiss? In theory, this seems to be a no-brainer. If you were asked this question in an introductory class in economics, the answer your professor would probably look for is: Right now. Everyone knows that a dollar now is worth more than a dollar later. Who knows what could happen in the future? You could die; the movie star could die; you could lose interest in kissing; the mysterious offer might go away. If you were in an Intro Psych class, “Right now” is again the best answer. Our minds have evolved to appreciate the economists’ insight about the value of a bird in the hand. So, we are temporally greedy; we often choose one marshmallow now rather than two marshmallows in the future.

Loewenstein finds that it’s more complicated. The graph below shows how much people will pay to get a certain positive outcome (like a kiss) or avoid a certain negative outcome (like an electric shock). This is calculated as a proportion of how much they would pay to get it or avoid it immediately.

As you can see, people prefer to get the kiss after a delay of a few days—they will pay more to get it in three days than to get it in three hours or twenty-four hours. But they don’t want to wait too long— they pay more for a kiss in three days than in one year and would rather have it now than in ten years.

The same preference for a delay shows up when you ask the question in another way with a different positive experience. Given the options below, 84% of subjects prefer Option B, waiting until next weekend for the fancy French meal.

What about a painful experience? Go back to the graph and look at “Shock” and you’ll see that people would rather have the shock sooner than later, which goes against the textbook view that you should want to put off bad experiences for as long as possible. (This is for the same reasons you should want to have good experiences right away—most of all, delay raises the odds that the experience won’t happen, which is bad for good experiences and good for bad experiences.)

What’s going on here, argues Loewenstein, is the pleasure of anticipation and the pain of dread. It’s fun to hold back on the kiss, imagining what it will be like. It’s unpleasant to have to worry about the shock; we’d rather get it over with.

Like any good study, the findings raise all kinds of questions. Why is three days the optimal time to wait for a kiss? (Why not three hours or one year?) Why do financial gains and losses (Gain $4, Lose $4, and Lose $1000) follow the more expected pattern where we prefer to get the good thing right away and put off the bad thing for as long as possible? Do people from different societies tend to differ in the pleasure they get from anticipation and the pain they get from dread?

2.

Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert, “A wandering mind is an unhappy mind,” Science 330 (2010), 932.

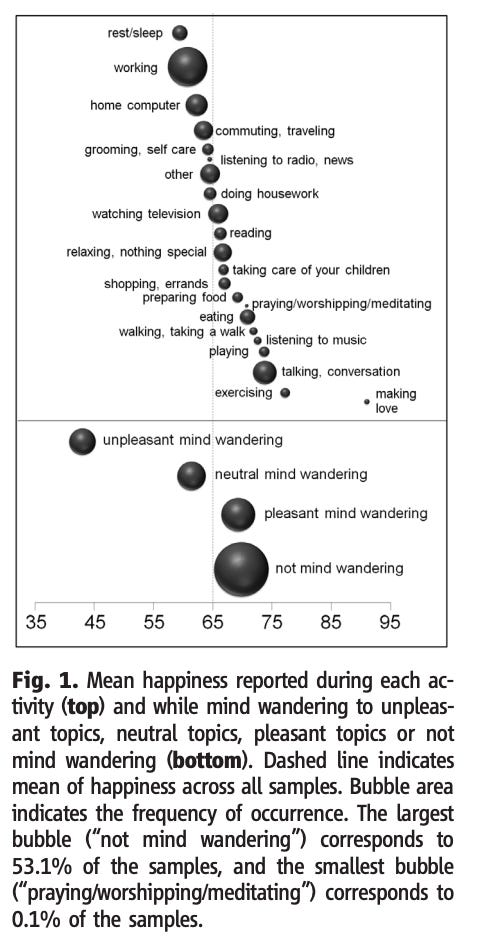

In this one-page paper published in Science, Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert report a study that used an “experience sampling” method—an iPhone app that pestered their subjects at random parts of the day. When it went off, they had to answer a happiness question (“How are you feeling right now?”), an activity question (“What are you doing right now?” with a menu of twenty-two everyday activities), and a mind-wandering question (“Are you thinking of something other than what you’re currently doing?”).

This figure summarizes the results.

I mentioned this paper a few weeks ago in a post called Life is Good, where I cited one of its findings: Taking all their responses together, the average rating is 65 on a scale from 0 to 100. Most experiences fall on the happy side of the scale. This, along with other findings I discuss, supports the conclusion that life is, for the most part, worth living.

Two other cool findings emerged from this study, as well.

First, people’s minds wandered a lot. About half the time, the average person is thinking about something other than what they are doing.

And second, mind-wandering isn’t that much fun. People tended to be less happy when their minds were elsewhere. This is surprising, especially considering how much mind-wandering is voluntary. Apparently, when we can think about whatever we want, we often go to dark places. This lure of negative thoughts strikes me as a fascinating and unintuitive fact about the mind, so much so that I wrote a good part of a book about it.

3.

Redelmeier, Donald A., Joel Katz, and Daniel Kahneman. "Memories of colonoscopy: a randomized trial." Pain 104.1-2 (2003): 187-194.

Imagine it’s the mid-1990s, and you’re going to the hospital for a colonoscopy. Back then, this was a painful procedure, so much so that people often refused to return for a follow-up. You have agreed to be part of a study, but you won’t find out what it’s about until the procedure ends. Before the procedure begins, you are given a hand-held device to record how much pain you are experiencing every 60 seconds.

Half of the subjects in this study get a normal colonoscopy. The other half—imagine that you are in that group—gets something extra:

Modified care consisted of a non-pharmacologic intervention … To do so, the tip of the colonoscope was allowed to rest in the rectum for up to 3 min prior to removal (no suction, inflation, or added anaesthetic).

That’s right—your procedure would have an additional unnecessary period of discomfort. This seems sadistic, but here’s the logic (my emphasis):

The goal was to minimize the level of pain during the final minutes of the procedure and thereby allow the patient to retain a more positive memory of the experience. … Thus, modified care lengthened the duration of the procedure but resulted in final moments that were less painful. Our hypothesis was that the intervention might lessen patients’ memory of the pain of colonoscopy and allow individuals to retain a more favorable (less unfavorable) impression of the experience.

And this is exactly what they found.

In agreement with theory, adding a short interval of minimal discomfort to the final moments of the procedure caused patients to retain a more favorable (less aversive) overall memory of the experience. The intervention caused about a 10% relative decrease in the overall memory of pain, a 10% relative increase in the number of patients who returned for follow-up, and suggested that more effective interventions are needed in practice.

When we look back on our experiences, endings matter. An experience that ends less painfully is recalled as better than one that ends with more pain—even if this first procedure involves additional mild pain.

Other experiments reveal duration neglect—the length of an experience has little effect on how we remember it. In reality, two enjoyable weeks of vacation contain more pleasure than one enjoyable week of vacation. But we remember them as identical—That was a fun vacation. Or consider our memories of negative experiences. Imagine being in a cramped middle seat of the plane, with no in-flight entertainment, nothing to read, and your neighbor at the window constantly getting up to pee. Which is worse, doing this for four hours or eight hours? This is not a hard question, I hope, but when you think back on the experience, you will tend to remember the four-hour experience and the eight-hour experience as equally negative—What an awful flight.

This research shows us something important: There is a big difference between the pleasure and pain we experience and our recollection of this pleasure and pain. If you want to maximize the actual pleasure of your life, stay for two weeks at the Caribbean resort, but if you just want to have a good memory of the trip, save your money and come home after a few days. If you want the least unpleasant experience of a 1990-style colonoscopy, make sure they stop the minute it’s over; if you want a better memory of it, opt for some extra mild discomfort at the end.

Should you live your life to maximize the experience of pleasure and minimize the experience of pain, or should you plan things so that the memories of your life are as pleasant as possible? I’ve talked to enough people to know that many see this as a no-brainer—but they don’t agree on which answer is the obvious one.

(I have my own views here, and I’ll discuss them in another post.)

Some of the summaries below are adopted, with edits, from my books The Sweet Spot and Psych.

What about making a habit of spending more time remembering happy/meaningful events? Seems more actionable than trying to engineer experiences. So much of our plans can be out of our hands.

And if that sounds like an obvious idea it’s not one I had heard about until recently. Up until then I thought one’s only options during spare time were rumination, worrying, distraction or focusing on the present.

There’s also the possibility of imagining nice things that never actually happened 😎

"The pleasure of anticipation" reminds me of your lottery post.

Anticipation of travel gives lots of pleasure. One study suggests more pleasure than the trip itself:

https://adarose.com/blogs/news/vacation-anticipation-always-plan-for-your-next-trip#:~:text=According%20to%20a%20study%20from,and%20months%20before%20the%20trip.