Life is good

Or is it? Do our waking moments contain more pain than pleasure?

The philosopher David Benatar believes that life is not worth living. He doesn’t recommend that we kill ourselves, but he does advocate antinatalism—the view that it’s wrong to create new people. (For more on Benatar, check out this New Yorker profile by Joshua Rothman.) In a twist on this, the philosopher Thomas Metzinger has proposed “digital antinatalism”—the view that we shouldn’t create artificial sentient beings because it would increase the amount of suffering in the world.

I find this antinatalism an interesting view, in large part because I find it so implausible. I enjoy my life and don’t look forward to it ending. I am glad to have played a role in creating other sentient beings (my sons). I’m not sure how I feel about creating artificial people, but I find the idea of a Star Trek-like future with trillions of humans spreading across the universe to be appealing. I’m a natalist.

But maybe I’m wrong. I’m reading Benatar’s book The Human Predicament with pleasure—he’s a clear and thoughtful writer with an occasional flash of dry wit.

Benatar makes several arguments in his book (including the claim that death is also a terrible thing), but I want to focus here on the claim that I find most provocative, which is that

there is much more bad than good even for the luckiest humans.

To make his case, Benatar starts by discussing how much physical unpleasantness even the best of lives has

Even in good health, much of every day is spent in discomfort. Within hours, we become thirsty and hungry. … When we can access food and beverage and thus succeed in warding off hunger and thirst for a while, we then come to feel the discomfort of distended bladders and bowels. … We also spend much of our time in thermal discomfort—feeling either too hot or too cold. Unless one naps at the first sign of weariness, one spends quite a bit of the day feeling tired. Indeed, many people wake up tired and spend the day in that state. … Itches and allergies are common. Minor illnesses like colds are suffered by almost everybody. … Many women of reproductive years suffer regular menstrual pains and menopausal women suffer hot flashes. … Conditions such as nausea, hypoglycemia, seizures, and chronic pain are widespread.

Then, he turns to a list of more psychological negatives, including the following.

We encounter inefficiency, stupidity, evil, Byzantine bureaucracies, and other obstacles that can take thousands of hours to overcome—if they can be overcome at all. Many important aspirations are unfulfilled. Millions of people seek jobs but remain unemployed. Of those who have jobs, many are dissatisfied with them, or even loathe them. Even those who enjoy their work may have professional aspirations that remain unfulfilled. Most people yearn for close and rewarding personal relationships, not least with a lifelong partner or spouse. For some, this desire is never fulfilled. For others, it temporarily is, but then they find that the relationship is trying and stultifying, or their partner betrays them or becomes exploitative or abusive.

He has a lot more to say about the miseries of everyday life. And then he writes, vividly and sympathetically, about those who are particularly unfortunate.

there is an atrociously diverse range of harms that people suffer at the hands of other humans, including being betrayed, humiliated, shamed, denigrated, maligned, beaten, assaulted, raped, kidnapped, abducted, tortured, and murdered.

He continues, describing the suffering of those with terrible burns, cancer, locked-in syndrome, and major depression.

It’s easy, though, to imagine a counterpart to Benatar’s miserable descriptions—one that focuses on the good stuff. It would begin with how life contains all sorts of physical pleasures, such as delicious food, hot baths, good coffee, good whiskey, good sex, and so on. (Your own list may vary.) Then there are the psychological positives of a life well lived—the many ways to love and be loved, the satisfaction of interesting work, the pleasure of spending time with good friends, the joy of getting lost in a good book or movie, and on and on and on.

Benatar is well aware that life contains these good things. But he maintains that the negatives carry more weight. This is in part because pain is longer-lasting than pleasure.

the most intense pleasures are short-lived, whereas the worst pains can be much more enduring. Orgasms, for example, pass quickly. Gastronomic pleasures last a bit longer, but even if the pleasure of good food is protracted, it lasts no more than a few hours. Severe pains can endure for days, months, and years. Indeed, pleasures in general—not just the most sublime of them—tend to be shorter-lived than pains. Chronic pain is rampant, but there is no such thing as chronic pleasure

He adds that pain is also more intense and asks rhetorically.

Would you trade five minutes of the worst pain imaginable for five minutes of the greatest pleasure?

I certainly wouldn’t. And I agree more generally about the pain/pleasure asymmetry. There is no pleasurable mirror image of a long period of horrific torture or severe depression.

In the end, though, the balance of pain and pleasure that people experience seems like an empirical question. Yes, the negatives have the potential to be far worse than the positives are good, and, yes, there are some people in situations where the negatives are so terrible that they would be better off dead. But it’s an open question how things will shake out for the average person, let alone for “the luckiest humans.”

Right now, as I type this in my study, I am a little hungry, and my leg aches from an old injury. There is an email I just received that angers me, and I’m trying not to think about it. But I feel refreshed after a good night's sleep; it’s fun to work through Benatar’s interesting work; and I’m drinking good coffee. For me right now, the positives outweigh the negatives. Life is good.

I’m not unusual here. Pollsters and social scientists often ask people how they think about their lives, and no matter how you phrase the question, most people say that they are happy (see the preface of my book The Sweet Spot for a review). When asked to rate their lives on a scale of one (“the worst possible life for you”) to ten (“the best possible life for you”), a strong majority of people describe their lives as far above the midpoint; when asked to choose from a list of descriptors, a strong majority of people describe themselves as “rather happy” or “very happy.”

Doesn’t this settle the issue?

Benatar is not convinced. He says most people are just wrong:

people are very unreliable judges of the quality of their own lives.

He summarizes some well-known psychological processes that can lead us to overestimate how good our lives are. These include a general optimism bias, the process of habituation (if we experience something long enough, we tend not to notice it), and a tendency to think in comparative terms, judging our situation based on our perception of how others are doing. As a result of this comparative mode of judgment,

bad features of all human lives are substantially overlooked in judging the quality of one’s life. Because these features of one’s life are no worse than those of other humans, we tend to omit them in reaching a judgment about the quality of our own life.

For instance, when asked how good my life is, I don’t consider the discomfort of having to pee sometimes, because everyone suffers from that. So I think my life is better than it is. As Benatar puts it,

The fact that we fail to notice how bad human life is does not detract from the arguments I have given that there is much more bad than good.

Benatar is making a distinction here between what he calls “subjective assessment” (how we think our lives are) and “objective wellbeing” (how our lives really are). He admits that they relate to one another—

a positive subjective assessment [can improve] one’s objective wellbeing.

—but for him, in the end, it’s objective well-being that counts. And, whether we know it or not, objectively we are all doing badly.

This argument puzzled me when I first read it. Can we be wrong about being happy, about having a good life?

But I’ve come to agree with Benatar. Consider this dialogue:

—I hate it when we bring the whole family over to your parents over the holidays.

—Do you? You do complain a lot. But you seem to have the best time—swimming in the lake with the kids, going for ice cream, snoozing in the hammock. Honestly, I never see you smile and laugh so much as when we take these holiday trips.

Or this one:

—That was a great dinner with the Joneses. Can’t wait to do it again.

—Really? You didn’t seem very happy. You were scowling the whole time, you drank a lot and tried to pick a fight with Stella. And you hardly ate your rigatoni.

These dialogues seem plausible to me. We can be wrong about how happy we were during some period of our lives, perhaps due to problems with memory, or because we attend to some things but not others, or because we have too-high or too-low expectations.

Maybe this is true for how we think of our lives as a whole. Benatar suggests that we fail to appreciate just how bad things are in part because our expectations are so low.

Most humans have accommodated to the human condition and thus fail to notice just how bad it is. Their expectations and evaluations are rooted in this unfortunate baseline. Longevity, for example, is judged relative to the longest actual human lifespans and not relative to an ideal standard. The same is true of knowledge, understanding, moral goodness, and aesthetic appreciation. Similarly, we expect recovery to take longer than injury, and thus we judge the quality of human life off that baseline, even though it is an appalling fact of life that the odds are stacked against us in this and other ways.

If things became better, we’d look back and see how miserable we once were.

So I agree with Benatar that we can be mistaken about the overall value of a particular event or even an entire life. But what about the pleasure or pain of an experience that we are currently having? Can we be wrong about that?

Imagine that it’s a hot day, and you jump into a cool pool. At first, you gasp and shiver, but gradually you acclimatize, and soon, it feels just right. You then float around, thinking happy thoughts, and then someone walks to the edge of the pool and you have the following conversation:

—How’s the water?

—Terrific! It was freezing when I entered the pool, but the water warmed up and now I feel great.

—Uhm, you’re mixed up. Nothing warmed up. It’s really the same temperature. You just got used to it.

This is a sensible response. Objective temperature and subjective experience of temperature are different things, and you got them confused.

But suppose the conversation went like this instead.

—How’s the water?

—Terrific! It was unpleasant when I entered the pool, but now I feel great.

—Uhm, you’re mixed up. You just got used to it. It’s really still unpleasant.

Huh? This is not a reasonable response. The experience is pleasant. This pleasantness is due to the psychological processes of habituation—getting used to things—but this doesn’t make it any less real.

We can be skeptical about how we assess our lives as a whole, then, but our judgments of pain or pleasure are more reliable. So let’s ask about them.

1. Experience Sampling

Fortunately, psychologists don’t only ask about happiness and life satisfaction, they also use a method called “experience sampling” to capture the hedonic value of everyday life. You can ask people at random moments (using an iPhone app, for instance) what their experience is like. This method isn’t entirely immune from the sort of biases that Benatar worries about, but it’s a purer reflection of how our lives actually are.

One recent study was done by Yoobin Park, Amie M. Gordon, and Wendy Berry Mendes. They drew on over 130,000 daily reports taken from over 14,000 individuals. Among other measures, they asked their subjects, at random times, “How are you feeling right now?” Subjects were given four options.

Positive and low-activated: calm, relaxed …

Positive and high-activated: energized, alert …

Negative and low-activated: bored, tired …

Negative and high-activated: nervous, afraid …

For a detailed description of the results by age, check out the graph below, but the gist is that, on average, people reported positive emotions, usually of the low-key sort, more than 70% of the time.

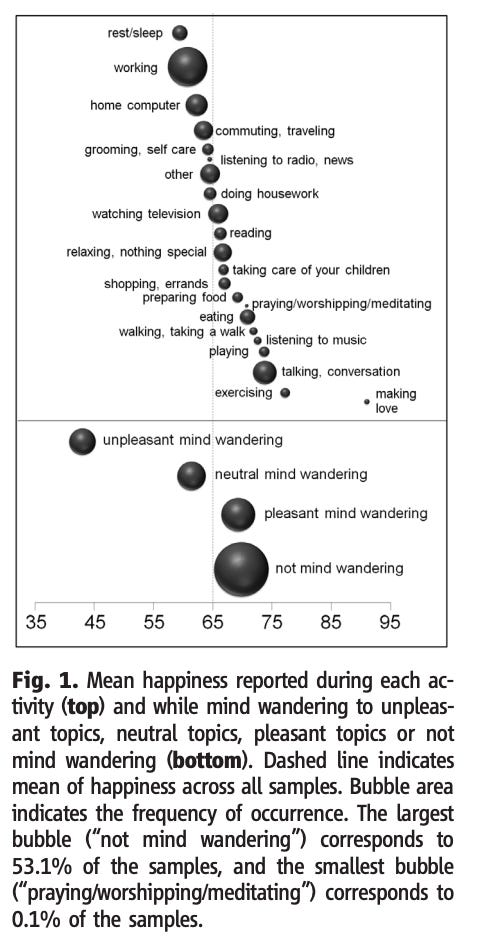

Or consider this 2010 study by Matthew A. Killingworth and Daniel T. Gilbert—a little gem of a paper that took up one page in the journal Science.

They asked people, at random times, how happy they were, and asked them as well what they were doing. The results are below. Their main finding—check out their title—is that people tended to be relatively unhappy when they were mind wandering. But for the purposes here, the important thing is that except for the category “unpleasant mind wandering”, all of the daily activities were above the midpoint (50 on a scale from 0 to 100). As you can see from the vertical line going up from the middle of the graph, the average happiness is 65.

I’d be interested to hear if there are exceptions to this, but as far as know, these results are typical—experience sampling studies find that, on average, life is good.

2. The Button

Some people think Benatar’s worry can be quickly dismissed; you don’t need to look at data. If life is bad, wouldn’t we want to kill ourselves? Most of us don’t, so life must be better than non-existence.

This is not a convincing argument. There are other reasons why we wouldn’t choose suicide even if our lives are miserable. Perhaps we don’t want to cause terrible grief to those who love us, or we believe things will eventually get better, or we think the afterlife will be worse. There’s also an instinctive aversion to self-destruction. Thomas Metzinger puts it like this:

I claim that our deepest cognitive bias is “existence bias”, which means that we will simply do almost anything to prolong our own existence. For us, sustaining one’s existence is the default goal in almost every case of uncertainty, even if it may violate rationality constraints, simply because it is a biological imperative that has been burned into our nervous systems over millennia.

But what about temporary periods of unconsciousness? There is nothing aversive about this—there is no biological imperative against brief naps.

Sometimes such unconsciousness would be welcome. I was recently on a five-hour flight to Las Vegas. The internet didn’t work, there were no movies, I was in an uncomfortable seat, and I didn’t feel like working or reading. I just wanted the flight to be over. Life wasn’t good and if I could fall asleep, I would be happy to.

What if we had access to a button that we could press to strip away our consciousness for certain fixed periods? Because sleeping isn’t always practical, imagine that during these periods, we would talk and act exactly as we normally would and we would later remember everything that happened. But we’d be zombified, unconscious, on auto-pilot. Presumably, we would hit the button when the negatives of life outweigh the positives, such as when undergoing a painful dentist procedure, fixing an overflowing toilet, or attending a faculty meeting.

How often would we hit the button? I did a Twitter poll.

To my surprise, most people would largely stay away from the button—only about one in nine would use it more than half the time. Most of the time, then, for most of the people who responded to my poll, life is good enough to stick around for.1

Two caveats:

To best engage with Benatar’s argument, I’ve been assuming here that the way to assess a life, to see whether it is worth living, is to think about the balance of pleasure and pain. But this isn’t my own view. In The Sweet Spot, I argue that

there is more to a life well lived, such as how meaningful it is and how morally good it is. So, while pleasure and pain obviously matter, I’m not a psychological hedonist.

It’s a fair objection to say that the Experience Sampling studies, and certainly my own Twitter polls, assess the lives of the relatively fortunate. There isn’t much data from those who are very poor, in prison, suffering from terrible chronic illnesses, and so on. And so when thinking about how much pleasure the average human experiences, these methods likely give us estimates that are too high.

Still, we have learned something. The evidence does not support Benatar’s claim that

there is much more bad than good even for the luckiest humans.

Instead, it turns out that even for the average psychology subject or someone who follows me on Twitter, life is more good than bad. Whew!

I wonder if pleasure and pain belong in the same equation. After all, Pandora's box didn't contain all the evils of the world, plus pleasure. Actually, on refection there might be a voice in my head ready to argue that pleasure was one of the evils...

I'm probably too dismissive of antinatalism: I tend to lump it into the 'pointless rhetorical flourish' bin, along with certain brands of 'longtermism' and 'hard determinism'.

I used to work in a classy bookshop and the most heavily shoplifted sections were cooking and philosophy. Cooking was right by the front entrance and the books were on the expensive side. What was philosophy's excuse? Readers skilled at justifying their actions, was my feeling.

I did give some thought to the ethics of having a child, before my daughter was born. I back-and-forthed for a couple of weeks, weighing the evils of the world and its imminent collapse into barbarism. In the end, like the Greeks, I found in favour of hope. I couldn't honestly say that my situation was worse than that of my ancestors, for whom the prospect of raiders on horseback, sweeping over the hills killing and burning everything they encountered, was very real. I'm glad they rolled the dice. I hope my decedents will be too.

...on the other hand, maybe I'm just stealing philosophy books.

It’s weird logical fallacy to conflate pain/suffering with the moral equivalent of bad. The idea you could slot our experiences in one of two boxes, always, is just silly. Life is complex and messy — a continuum of sadness and joy and everything in between.