My friend thinks it's a good idea for us to spend most of our time with AI companions

Is he right? How should I respond? (Part 1)

What will happen if we ever have good AI replacements for people?1

I wrote about this in a recent Substack post called Be Right Back. I wasn’t thinking of humanoid robots; I focused on the more realistic possibility that we would have AI substitutes that we could talk to over our phones or through virtual assistants like Alexa and Google Home. I considered a few of the options that people would find attractive, such as celebrities:

Many people would pay a lot to have regular conversations with Oprah Winfrey. Real Oprah would be best, but I’d bet that a simulation of Oprah—or George Clooney, Barack Obama, or Princess Diana—would be very satisfying. These simulations could act as friends, therapists, romantic partners, or have more specialized usages. An undergraduate gifted in physics might benefit from regular conversations with simulations of Richard Feynman or Albert Einstein; an aspiring writer might enjoy working alongside simulations of Stephen King, Margaret Atwood, or Zadie Smith.

And parents:

Parents are often separated from their children, sometimes for long periods, such as when they go on a business trip or a military deployment. Simulations could help alleviate the children’s distress. A 5-year-old could come home from school every day and talk to a simulation of her absent mother or father about what happened during her day. This could work for shorter periods of separation as well—a child who is anxious about starting daycare might bring with him simulations of his parents to help him settle down during naptime.

And the dead:

Some of us are lucky enough to find what we can call—and, yes, this is a clichéd phrase, but I’m going to use it—our soulmates, and here, if things go well, we’ll spend years and years with them, and then someone will die, and the other will be left alone and bereft. … We can’t get them back. Dead is dead. But what about a simulation? Not some ridiculous chatbot or science fiction robot, but something that can talk to who is just like who you lost, so much so that you can pretend, or come to believe, that it is them.

I called this last possibility “both a blessing and an abomination.”

My focus was on substitutes for specific people, but AI has the potential to create wholly new characters. This is happening now in a limited way. Many of the individuals we interact with over the internet are “bots,” and sometimes we don’t know this. Millions of people regularly talk with AI “boyfriends” and “girlfriends” through the service Replika.

A couple of weeks ago, I was having a beer with a friend who read my post. I was going on about how dystopian it would be to live in a world where we regularly dealt with substitute people. And my friend—not a freak, a popular guy with lots of friends and a loving family—said:

“I don’t get what you’re worried about. It sounds great to me.”

I was a bit shocked, but when I tried to explain what bothered me, I found it hard to make the case. I want to reconsider the issue, first going over the potential benefits of these AI substitutes (here, in Part 1) and then moving to my concerns (later, in Part II).

The Case For

My friend reminded me that I couldn’t be all that concerned about AIs, given that I was one of the authors of this paper that came out about a month ago. (Michael Inzlicht was the lead author and initiated the project; the other co-authors were C. Daryl Cameron and Jason D’Cruz). The title and abstract certainly sound pretty cheerful about our AI companions.

And, yes, I do praise empathic AI.2 I think that the benefits of AI companions are obvious.

Have you ever been lonely? Really lonely? Here is an excerpt from Zoë Heller’s book, Notes on a Scandal: What Was She Thinking?, in which Barbara, a bitter elderly woman, is thinking about a fellow teacher: (Trigger warning—this might break your heart).

People like Sheba think that they know what it’s like to be lonely. They cast their minds back to the time they broke up with a boyfriend in 1975 and endured a whole month before meeting someone new. Or the week they spent in a Bavarian steel town when they were fifteen years old, visiting their greasy-haired German pen pal and discovering that her handwriting was the best thing about her. But about the drip, drip of long-haul, no-end-in-sight solitude, they know nothing. They don’t know what it is to construct an entire weekend around a visit to the launderette. Or to sit in a darkened flat on Halloween night, because you can’t bear to expose your bleak evening to a crowd of jeering trick-or-treaters. Or to have the librarian smile pityingly and say, “Goodness, you’re a quick reader!” when you bring back seven books, read from cover to cover, a week after taking them out. They don’t know what it is to be so chronically untouched that the accidental brush of a bus conductor’s hand on your shoulder sends a jolt of longing straight to your groin. I have sat on park benches and trains and school room chairs, feeling the great store of unused, objectless love sitting in my belly like a stone until I was sure I would cry out and fall, flailing to the ground. About all of this, Sheba and her like have no clue.

Loneliness is terrible. It ravages both body and soul. Here’s how a government study from last year put it:

[Loneliness] is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, stroke, depression, anxiety, and premature death. The mortality impact of being socially disconnected is similar to that caused by smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day, and even greater than that associated with obesity and physical inactivity.

If AIs could serve as friends, companions—and, who knows, romantic partners—to lonely people, then they would add so much happiness to the world.

Is this possible? I’m mostly interested here in possible future AIs, but at least some people seem to get something from interacting with the far inferior versions we have right now. Here is what some Reddit users say about ChatGPT.

One recent paper published in JAMA Internal Medicine reports a study in which the researchers randomly took 195 exchanges (from Reddit’s r/AskDocs) where someone asked a question and a verified doctor responded. Then, they had ChatGPT give its own response and gave the pair of answers—the human one and the AI one—to a team of healthcare professionals and asked them to compare them. People preferred the ChatGPT responses in most of the interactions. They also ranked them as more empathic. In fact, the ChatGPT had about ten times more of its responses rated “empathic” or “very empathic” than the doctors did.

Maybe this finding is more about physicians than about AI—perhaps the “verified doctors” were cold fish. But now consider this recent study published in PNAS.

A group of people were asked to describe something that they had experienced in the past. They got a response from either another person or from Bing Chat and were told that this response was either from a human or Bing Chat. So, there were four conditions.

Response by human, told that it was human

Response by human, told that it was Bing Chat

Response by Bing Chat, told that it was human

Response by Bing Chat, told that it was Bing Chat

They were then asked to rate how much they felt heard, how accurate their respondent was in understanding them, and how connected they felt to the respondent.

Again, AI won. People felt more heard, better understood, and more connected to Bing Chat. But, and this is important, they were also influenced by who they thought was responding to them. If they thought it was an AI—even if this was a lie—they felt less heard, understood, and connected. We are biased against AIs, then, but we actually prefer them.

Another just-published set of experiments asked participants to share good news with someone whom they believed was either a chatbot or a human. They were equally happy with both interactions. But they were less pleased when the chatbot—but not the human—shared its own good news with them; as the researchers put it, they didn’t like when AIs “went too far”.

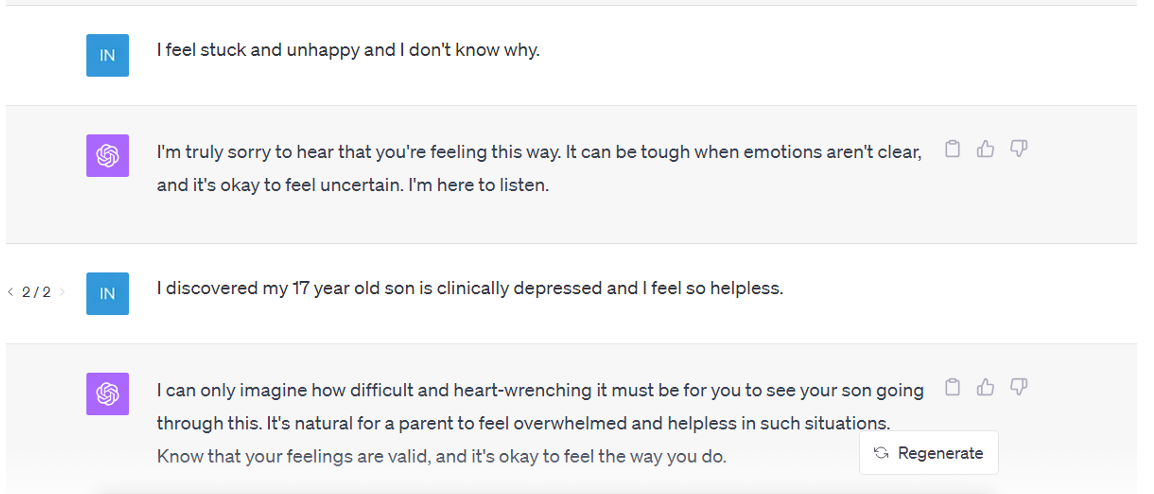

Here’s how Michael, Daryl, Jason, and I describe our own experiences:

In our own interactions with ChatGPT, we have been impressed by how well it simulates empathy, compassion, and perspective-taking (see supplemental information online). When we prompted ChatGPT to express empathy or compassion – but not to provide advice – ChatGPT seemed remarkably empathic. It expressed sorrow in response to our worries and joy in response to our successes. It validated our feelings, adopted our perspective, and reassured us that others feel similarly.

As an illustration, here are some chatbot dialogues with the first author.

Could you write better short responses?

Some people, including me and my co-authors in our paper, take these findings as evidence that AIs can already serve as good companions. Thinking about it more now, though, I’m more hesitant. The research discussed above, and all of the other studies that I know about, just look at very short interactions—the person writes something, and then the AI responds. It’s unclear how well AI would fare in a real conversation.

Yes, some people do become attached to current LLMs. But they are exceptions. The technology just isn’t there yet. I can ask Claude (my favorite AI right now) to pretend it is a therapist or a friend. But this is something to play around with; there’s no chance it will wrest me away from real human interactions. I know people who goof around with Replika, and they say it’s kind of fun, but they’re not going to leave their husbands and wives for it. Nobody is canceling appointments with their therapist. And Claude and the rest are nowhere near as addictive as Netflix, Twitter, and TikTok.

What’s missing? The obvious answers are intelligence, insight, and other deep capacities that humans possess. But while I think the obvious answers are right, there is something more basic that AIs lack. To replace humans, they must be able to talk to us. Not “talk” like Alexa, where you must enunciate your words carefully and intentionally and where the responses are tuneless and robotic. I mean, really talk. When I think of AIs of the future, I think of Samantha (played by Scarlett Johansson) from Her. You don’t have to see the movie—though you should; it’s terrific—just watch the trailer, and you’ll get what I’m saying.

Getting the voice right will be a huge thing. Samantha is warm, clever, and kind, but the voice might win us over even if she weren’t any of these things. One could fall in love with Samatha; it would be hard to become close to Alexa, Siri, or Google Home, even if they were made much smarter.

AI research is moving fast these days. I wrote the above two paragraphs over a month ago. Since then (May 14, 2024), a series of videos, including the one below, was released introducing GPT-4o, which seems to talk just like Samantha does.

Does the voice seem familiar? It turns out that OpenAI had approached Johansson to be the voice of GPT-4o, and she turned them down. Did they then purposefully choose an actress who sounded like Johansson? She thinks so, and her lawyers are investigating …

Anyway, assuming we can trust the demos, we have the voice now. The next steps are to make it more human, to somehow infuse it with empathy, intelligence, humor, and so on—or at least the appearance of these human traits.

How far are we from all this? Some would say we’re just around the corner; others—like my friend Gary Marcus at Marcus on AI—are skeptical; they think current Large Language Models are as good as they will ever get, and only a paradigm shift in how we construct these machines will give them human-like capacities. I’m agnostic myself. We’ll know soon enough.

I talked about the benefits of simulated people for those suffering from loneliness, but AI companions might also improve the lives of those who already have satisfying relationships with family and friends.

I talked with Russ Roberts about this. We discussed a world in which we could talk to simulations of great scholars, artists, teachers, and so on—with the simulations set up so that they are always available and interested in communicating with us. And Russ said (though he put it in a nicer way), that it were possible for him to pass the time conversing with the brilliant and creative Adam Smith, why would he ever spend his time with a schmo like me?

So what’s not to like?

.

Thanks to Mickey Inzlicht and Christina Starmans for comments on an earlier draft of this piece.

In our article, we explicitly state that we’re agnostic about whether AIs actually possess empathy. By “empathic AI,” we just meant “AI that appears as if it has empathy.” We define “empathy” as “resonating with another’s emotions, taking another’s perspective, and generating compassionate concern,” which is different from the narrower notion of “empathy” that I critique in my book Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion.

I'm constantly amazed at the different intuitions people have about this topic and look forward to future parts of this essay. The value of the Small Potatoes newsletter for me rests wholly on the fact that there is a conscious, thinking, emoting human awareness called Paul Bloom behind what's written here. (I mean… I assume there is?!) Assuming LLMs aren't conscious – and that feels like a separate discussion – there just can't be a real relationship between a human and an LLM! Of course, the fake relationship might be better than nothing in cases of extreme loneliness. Maybe a fake therapist is better than nothing because real therapy is so hard to access, and so forth. But the idea that anyone would *willingly* choose the fake version, for friendship or companionship or the feeling of being understood or heard, blows my mind…

The AI responses were far too feminine and problem oriented. It would annoy me greatly. Is there a version that focuses on solutions and progressing forward? As it stands, it seems like it would be worse for people's mental health than even a Freudian therapist would be.