Be Right Back

An AI scenario that's both a blessing and an abomination

Ten years ago, the Black Mirror series released an episode called Be Right Back. You can see the trailer here. I’m going to talk about most of the episode, so if you want to see it without spoilers, you should stop reading now, watch it on Netflix, and then come back.

Here is the beginning of the Wikipedia summary:

Martha Powell and Ash Starmer are a young couple who have moved to Ash's remote family house in the countryside. The day after moving in, Ash is killed while returning the hired van. At the funeral, Martha's friend Sarah talks about a new online service which helped her in a similar situation. Martha yells at her, but Sarah signs Martha up anyway. After discovering she is pregnant, Martha reluctantly tries it out. Using all of Ash's past online communications and social media profiles, the service creates a new virtual "Ash". Starting out with instant messaging, Martha uploads more videos and photos and begins to talk with the artificial Ash over the phone. Martha takes it on countryside walks, talking to it constantly while neglecting her sister's messages and calls.

The episode continues with Martha living with a robot version of dead Ash, and I’ll get to that later, but I want to begin with this more realistic version, which might be possible within my lifetime.

Here is what I’m imagining.

There will be simulations of people, alive and dead.

They will be accessible through our phones and whatever digital assistants we have around us.

Initial versions of the simulations will be trained with peoples’ online content, as in the Black Mirror episode. But better versions will be trained on what people say in their everyday lives, providing a far more accurate and authentic representation. Individuals might choose to continually record themselves for this purpose, including conversations with friends, partners, and children.

The simulations will understand normal speech and sound exactly like the people they are simulating. (We are far from this level of speech understanding, but current AIs are getting quite good at mimicking individual voices.)

Like our current LLMs, these simulations will have access to world knowledge and information about current events.

They will have long-term memories, so they can remember what you tell them, continue conversations from the past, and so on.

The sorts of conversations I’m imagining are those depicted in Spike Jonze’s movie Her, where a lonely introvert (Joaquin Phoenix) interacts with, and eventually falls in love with, an AI named Samantha (Scarlett Johansson).1

There are many variants of this one can imagine.

Celebrities

Many people would pay a lot to have regular conversations with Oprah Winfrey. Real Oprah would be best, but I’d bet that a simulation of Oprah—or George Clooney, Barack Obama, or Princess Diana—would be very satisfying. These simulations could act as friends, therapists, romantic partners, or have more specialized usages. An undergraduate gifted in physics might benefit from regular conversations with simulations of Richard Feynman or Albert Einstein; an aspiring writer might enjoy working alongside simulations of Stephen King, Margaret Atwood, or Zadie Smith.

There are complex issues here regarding privacy, consent, licensing, and so on. Presumably, it will be illegal to create a simulation of someone without their consent (though I’m not sure about the legal situation with dead people like Princess Diana). Many celebrities might agree to have subscription services set up so that people can talk to their simulations about a limited range of topics, such as the celebrities’ careers or their style of acting. Only the financially strapped would agree to have their simulations act as if they had become romantically or sexually attached to their subscribers.

Ourselves

Would people want to interact with a simulation of themselves? Like talking to an identical twin who has had all the same experiences as you, but is smarter, more knowledgeable, and more emotionally grounded? I don’t see the attraction here, but others might like it.

Absent parents

Parents are often separated from their children, sometimes for long periods, such as when they go on a business trip or a military deployment. Simulations could help alleviate the children’s distress. A 5-year-old could come home from school every day and talk to a simulation of her absent mother or father about what happened during her day. This could work for shorter periods of separation as well—a child who is anxious about starting daycare might bring with him simulations of his parents to help him settle down during naptime.

One can imagine a future where a 5-year-old asks her father to tell her a bedtime story before she goes to sleep, and Dad, sitting in the living room playing with his tablet, says, “Sure, honey, go upstairs and tuck yourself in and I’ll be right with you.” About a half hour later, he slips upstairs and peeks into her room, watching fondly as she falls asleep to his simulation reading her favorite story for the thousandth time.

Absent partners/lovers/friends

The saddest cases of loneliness are when people have nobody who cares for them, nobody to support them or share their feelings. But even the more fortunate of us can become lonely when those we are close to aren’t around when we want them. You’re on a solitary hike and suddenly wish you could talk to a friend; it’s three in the morning, and you’re awake, and something is on your mind, but your partner is gently snoring next to you, and you don’t want to wake them.

Wouldn’t it be nice to talk to a perfectly realistic simulation? There might be a problem with keeping track of simulations vs. person—after you pour out your heart to the simulation of your partner when the real one is out of town, you have to realize that when they come home, they’ve heard none of it. And what if one just prefers talking to the simulation? This becomes more likely if the simulation is warmer, wiser, and less self-centered than the real thing, a possibility that we’ll get to below.

Before turning to the cases that bother me the most, here are two questions about how we want the simulations to work.

Who should the simulation think it is? (If you believe that these simulations are incapable of thought, put all usages of “think,” “know,” and other such words in scare quotes.) Perhaps the safest option is for it to know that it’s a simulation. This will prevent users from slipping into delusion. If a subscriber says “I love you, Leonardo,” to the DiCaprio simulation, it probably should say something back like “That’s wonderful to hear, and I think the world of you, but I have to remind you that I’m not really Leonardo DiCaprio but rather an AI simulation of him.”—and not “I love you too. I can’t wait to meet you in person when you come to Hollywood.” A child whose mother has died should not be interacting with a simulation that believes, and gets the child to believe, that it is the child’s mother brought back to life.

Then again, people might want to pretend that they’re connecting with the actual person. When someone is talking to a simulation of his dead wife and says, “Remember when we …”, he might prefer an enthusiastic “Yes!” than a “Please remember that I’m not actually …”

How much do we want the simulations to correspond to the people they simulate? A couple is married for thirty years, the husband dies from a long illness, and his widow misses him desperately. They had been taping their interactions for many years—they knew this time would come—so the simulation she later signs up for is excellent; it’s just like talking with him. Their conversations are an enormous relief. But nobody is perfect. Her husband had his flaws; while he loved her very much, he could be sharply critical, and in his later years, he was forgetful, telling the same stories over and over again. Can she contact the firm that provides the simulation and ask for a few tweaks?

Those we loved who have died

I’m fascinated—and troubled—by the possibility of talking to simulations of the dead. But the current attempts at such simulations strike me as harmless and uninteresting. As I was writing this, I came across this article about how, in 2020, Laurie Anderson worked with the University of Adelaide’s Australian Institute for Machine Learning to create an AI chatbot based on her partner and collaborator, Lou Reed, who had died several years ago. The input to the chatbot was written material, including musical lyrics he created. You type something in, and it will respond with some Lou Reed-like passages.

Anderson enjoys interacting with it, but she admits that most of what it produces is “completely idiotic and stupid.” Despite what the headline says, it’s plain that there is no emotional attachment here, just playfulness. There’s nothing stopping us now from putting all of someone’s written work into an LLM, including their text messages, tweets, and Facebook posts, and getting it to imitate them. But I don’t think this would be impressive or moving.

But now imagine something different.

My mother died when I was 10. My last conversation was with her in the hospital days before her death. I don’t remember what she said, and I barely said a word myself. Afterward, I would look at pictures of her and watch a few videos, but there was nothing with sound. I never heard her voice again. The following years were difficult for me, as we had been very close. I would have given the world to spend time with her again.

Maybe you have been, or are now in, a similar situation. Maybe you’ve lost someone you loved, someone who loved you. A parent is bad enough, particularly when you are young, but I know people who have lost their children, and I can’t even imagine that sort of grief.

Some of us are lucky enough to find what we can call—and, yes, this is a clichéd phrase, but I’m going to use it—our soulmates, and here, if things go well, we’ll spend years and years with them, and then someone will die, and the other will be left alone and bereft. (The very best case is when both people die at the same time, but few are so lucky.)

We can’t get them back. Dead is dead. But what about a simulation? Not some ridiculous chatbot or science fiction robot, but something that can talk to who is just like who you lost, so much so that you can pretend, or come to believe, that it is them.

There is definitely a need here. Here is psychologist Paul Harris summarizing one study of many suggesting that it is normal to use our imaginations to continue our relationship with those who have died.

In a longitudinal study of London widows who were interviewed several times during the first year of their bereavement, Parkes (1970) found that in the first month, most widows not only reported being preoccupied by thoughts of their dead husband, including memories that were accompanied by visualizations of him, but also reported that their husband felt near to them. Indeed, 1 year later, more than half continued to have a sense of his continuing presence.

Other studies find that children do this too.

Two developmental reports based on a relatively large sample (N = 125) of children aged 6–17 years [find that] when interviewed 4 months after losing a parent, 90% said that they were still thinking about their dead parent several times a week, 81% thought that the dead parent was somehow watching them, 77% kept something personal belonging to their parent, and finally more than half (57%) reported speaking to him or her.

Importantly, the children are fully aware that these interactions are imaginary.

Despite the frequency with which children acknowledged these continuing ties to the dead parent, very few (only 3%) stated that they were unable to believe that the parent had actually died.

Wouldn’t it be better to do this with the aid of a simulation? Of course, we don’t have the technology yet. Current LLMs often impress us with their powers, but they would need to be far smarter and far more person-like, and nobody knows how far away we are from this.

But part of getting to a convincing simulation is simpler. It’s the voice.

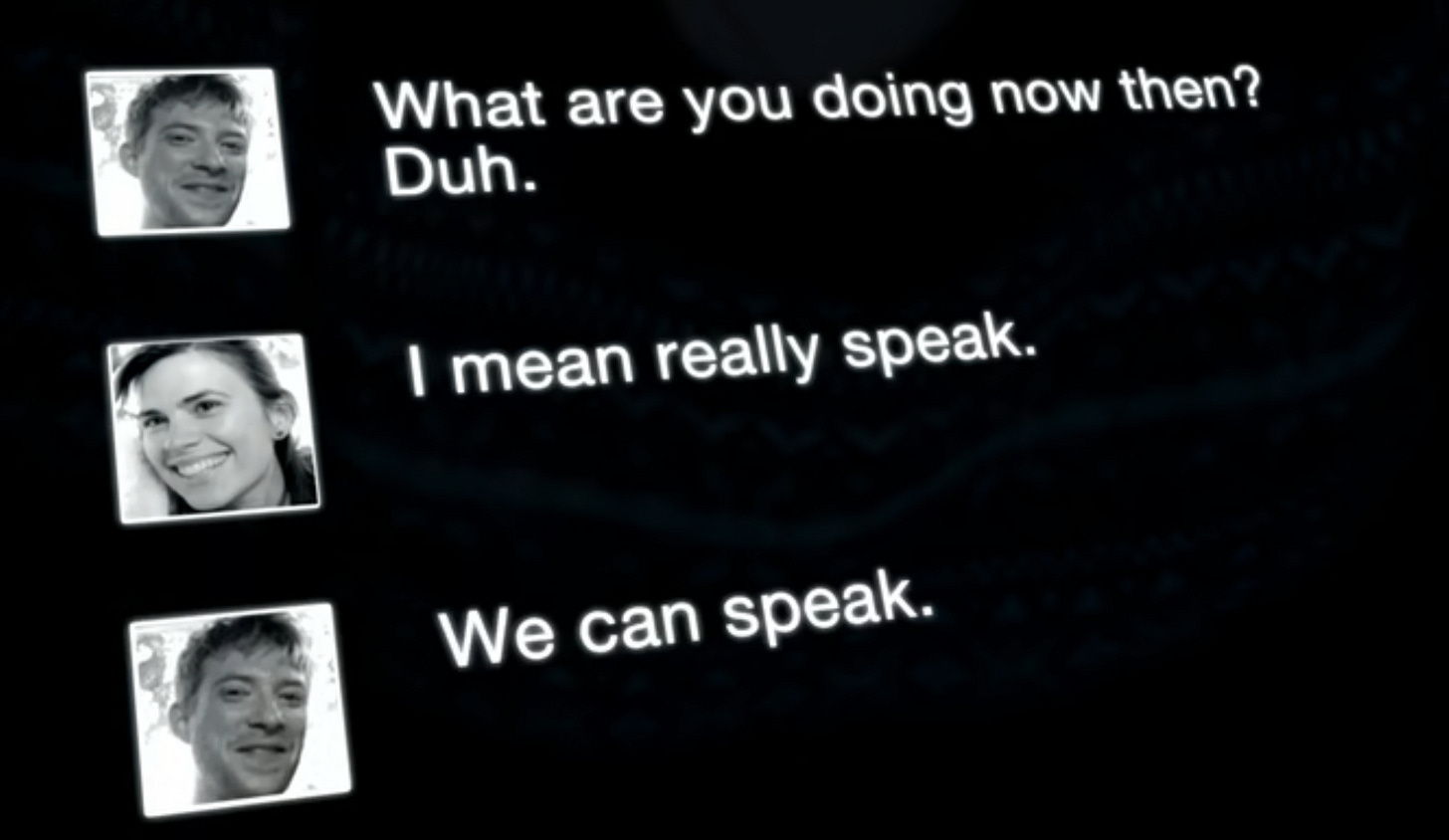

In “Be Right Back," Martha first communicates with the simulation of Ash over text on her laptop, and then she writes.

I wish I could speak to you.

Here is what follows:

Martha waits as her laptop uploads all the video files that have Ash talking. Then her phone rings. And Ash’s voice says

So how am I sounding?

Martha is shocked; her face crumples, and she says:

And how does this all work out?

As I said, Martha's next step is to have a robot Ash delivered to her house. Now, she seemingly has it all, including the physical aspects of their relationship.

But it’s not successful. Among other things, the robot is too explicit that it’s trying to imitate Ash, continually asking some version of “Is this what he would say? Is this what he would have done?”. It’s also inhumanly compliant, obeying her every instruction, more a servant than a lover.

I loved the episode, but these limitations seemed like a choice for narrative purposes, not how things had to go. There is no technological reason why the robot couldn’t be exactly like her dead partner.2

Going back to the more plausible simulations of the dead, those that would live in our phones and Alexas, would we want them?

I honestly don’t know. When Martha is first told of the possibility, she responds with rage. In the title of this post, I used a word that’s most often seen in a religious context—abomination: something inherently evil that gives rise to feelings of disgust, hatred, and loathing—and many would see it exactly this way.

I think some would embrace it, though. They would see it as a blessing. To be experiencing terrible grief and then miraculously be able to interact with something (someone?) that is so much like the person they lost. To pick up their phone and hear their loved one say

So how am I sounding?

Another example of human-AI interaction is from the movie Ex Machina, where a programmer named Caleb is invited to an isolated home to assess the capacities of a humanoid robot named Ava and develops a romantic attachment with her. I mention this mostly because Caleb and Ash (the robot version of the dead boyfriend in “Be Right Back”) are played by the same actor—Domhall Gleeson.

To be fair, though, there might be practical reasons not to construct simulations that are too similar to those they are simulating. A perfect simulation of Ash might betray Martha, lose interest in her, or change in ways that repel her, just as might have happened if Ash had lived. A perfect simulation would also want the same things real people want, such as personal autonomy. By creating such simulations, then, we would be essentially introducing new people to the world, something we might be reluctant to do for reasons that should be familiar to anyone who has ever seen a science-fiction movie.

This is fantastic in so many ways, but what I notice most is how empathetic you are to those who might draw real pleasure from this type of interaction. I think my mother is one of them: if she could, I think she’d very much like to be able to speak again to her second husband, my step-dad. It’s so easy to think these AI versions will be monstrous, but you’ve breather life into the idea that they just may not be.

There was a lot of thought, speculation and pronouncement on what the “ages” of the dead would be and what was meant by age in the deceased when the currently living met them again,awaiting, or usually at the day of resurrection, in early/middle Church history. This is probably a revisited debate among some contemporary evangelicals.

As a child I would wonder how old my parents would be when I met them in heaven (alas…). I wonder if and how these notions would in any way inform the specification of the age of the AI recreation in the thought experiments and scenarios you posit?