Implicit bias: All your questions answered

Including: Are we all racist?

Even if you’re not a psychologist, I bet you’ve heard of implicit bias. In 2016, Hilary Clinton mentioned it in a debate with Donald Trump, saying, "Implicit bias is a problem for everyone." Five years later, Merrick Garland was questioned as part of his confirmation hearing for becoming Attorney General, and one of the senators asked him about this about implicit bias.

Does that mean I'm a racist no matter what I do or what I think? I'm a racist but I don't know I'm a racist?"

Garland responded.

Implicit bias just means that every human being has biases. That’s part of what it means to be a human being. And the point of examining our implicit biases is to bring our conscious mind up to our unconscious mind and to know when we’re behaving in a stereotyped way. Everybody has stereotypes. It’s not possible to go through life without working through stereotypes. And implicit biases are the ones that we don’t recognize in our behavior. That doesn’t make you racist, no.

Is he right?

Well, let’s get into it. Many people think implicit bias is woke nonsense, non-replicable junk that has been promoted to support the far-left agendas of social psychologists. They’re wrong. Some social psychologists are weirdly dogmatic about the topic, endorsing claims about implicit bias that go way beyond what the studies show, and smearing their critics as racist. They’re wrong too. A recent analysis of Intro Psych textbooks found that most of them get a lot wrong about implicit bias, and don’t get me started on what you’ll read in the popular press.

Good thing I’m here to clear things up.1

What are explicit beliefs and attitudes?

These are the beliefs and attitudes we have and know we have. I believe that the Dutch tend to be taller than the Japanese. I believe that, at least in North America, men are more likely than women to be structural engineers and Jews tend to vote for Democrats. And I know I believe these things.

Explicit attitudes are much the same as explicit beliefs, except they involve evaluations, not facts. I might admire one group and be afraid of another. Beliefs and attitudes often work together—you might not like a group (an attitude) because you think they are awful (a belief).

When the beliefs and attitudes are about human groups, like these, we call them stereotypes. Some are true; some are false; some are positive; some are negative.

How do we measure explicit beliefs and attitudes?

Usually just by asking.

Of course, we are sometimes shy about talking about certain beliefs and attitudes because they are taboo. Depending on your social circle, you might be comfortable expressing your (fully explicit) negative beliefs and bad attitudes toward police officers, journalists, or white women—but if you had negative beliefs and bad attitudes toward Asians, Jews, or Black women you might keep them to yourself.

Still, people do tend to be more honest in anonymous polls and questionnaires, and psychologists, sociologists, and other social scientists are able to explore how beliefs and attitudes about these groups vary over space and time. For instance, here is data between 1933 and 2000 about the extent to which white respondents say that Black people possess certain negative traits.

And here is an indirect measure of attitude—whether white people would vote for a qualified Black person to be president:

The historical trend in belief and attitude is obvious. People used to be a lot more (explicitly) racist than they are now.

Now, you might worry that people lie even in these anonymous polls (maybe they worry that they aren’t so anonymous after all). If so, then the historical change reflects people’s discomfort in expressing certain beliefs and attitudes, not a shift in beliefs and attitudes themselves. This might be part of it. But, still, the idea that these are real shifts in beliefs and attitudes does have independent support. For instance, both times he was elected president, Obama did just as well with white voters as previous Democratic candidates such as Clinton.

What are associations?

If you have two experiences close together in time and space, they will become connected in your mind—thoughts of one will elicit thoughts of the other. The whine of the dentist's drill makes me anxious because of my previous bad experiences at the dentist's office. Pavlov’s dog salivates at the sound of the metronome because of its previous association with meat powder; Skinner’s rat darts toward the side of the maze that was previously associated with a delicious treat. If you say “John, Paul, George”, I’ll think “Ringo”; play the Canadian national anthem, I expect a hockey game to begin. My friend and fellow podcast host David Pizarro (more about him later) hears the distinct hiss of the HBO intro, and feels a flash of joy, because it used to mean that The Sopranos was about to come on.

Some scholars think that forming associations is all the brain does. This was the position, centuries ago, of philosophers such as John Locke and David Hume. It was the view of the behaviorists, who saw all learning as the association of different stimuli (classical conditioning) or the association between behaviors and rewards or punishments (operant conditioning). And it’s the view held by many cognitive scientists these days, who see “deep learning” as the foundation of all of mental life—we are nothing more and nothing less than a powerful statistical learning machine, adept at discovering patterns in the environment. Brains are association machines.

I don’t buy this extreme view—there are a lot of non-associationist mental processes such as our capacity for mathematical and logical reasoning. But I don’t doubt the power of associations.

What are implicit biases?

They are the associations that we have with human groups, often with some sort of positive or negative feelings. Some examples are associating elderly people with incompetence, men with violence, women with nurturance, and Jews with finance.

Do such associations often align with explicit beliefs and attitudes?

Yes, they often do.

If I repeatedly eat delicious food at a certain restaurant, I’ll develop a positive association with that restaurant, and I’ll also come to believe (explicitly) that it’s a good restaurant and come to evaluate it (explicitly) in a positive way—5 stars! If I go to a new country and people are rude and my experiences are unpleasant, I will have bad associations with the people there and negative beliefs and attitudes.

Do such associations always align with explicit beliefs and attitudes?

Here’s where it gets interesting. No—they don’t.

A simple example that doesn’t involve human groups is acquired phobias. You have a terrible experience on a plane and now you’re afraid of flying. You have a bad association with planes and air travel. You might know perfectly well that planes are safe—even as your hands sweat at the thought of getting into one. (You might even seek treatment for your aviophobia—which only makes sense if you appreciate that the fear is irrational; it doesn’t match your considered beliefs.)

As an example with human groups, consider dentists. My experience with dentists has been unpleasant, and I think it’s fair to say that I have a negative association with them. (I flinch a bit when I see them with their white coats and little mirrors.) But, explicitly, I have absolutely nothing against dentists.

Can associations be involuntary?

Yes, see the examples above. Nobody wants to have a phobia.

When it comes to associations with groups, the civil rights leader Jesse Jackson provides a poignant illustration:

There is nothing more painful to me at this stage in my life than to walk down the street and hear footsteps... then turn around and see somebody white and feel relieved.

This is a negative association that Jackson wishes he didn’t have.

Can we control the associations we form?

To a large extent, no. You experience what you experience. If a cookie has a certain smell, you’ll associate that smell with the cookie. Pavlov’s dogs couldn’t opt out of associating the sound of the metronome with the smell and taste of the meat powder. Given my experiences, there’s nothing much I can do about the negative associations I have with dentists.

But sometimes yes. We do have some control over our environments, over what gets into our heads. There are people on Twitter who like to post videos of Black people committing crimes. If I choose to spend a lot of time watching these videos, certain associations between race and crime will strengthen in my mind. That’s my choice. On the flip side, someone who wants to develop a positive association—between women and science, say—can do the opposite, and work to expose themselves to contexts where they see women scientists.

Are associations unconscious?

It depends on what you mean by unconscious. Are they hidden in the recesses of your mind—like your wish to sleep with one of your parents and kill the other—only extracted through the skills of a trained Freudian psychoanalyst? No.2

However, they are not accessible in the same way as explicit beliefs and attitudes. Sometimes you are only aware of having an association when it’s triggered. The most famous literary example is from Swann’s Way, the first book of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, where the narrator talks about the flood of memory after biting into a madeleine dipped in tea.

No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory—this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me it was me. . . . The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it. And all from my cup of tea.

The association here was triggered by taste. Just thinking about madeleines (or apparently, just looking at them) doesn’t elicit this explosion of pleasure and memory.

Less dramatically, I sometimes have the experience of seeing someone I know, or hearing their voice, and then having certain feelings arise (such as simple warmth), but I couldn’t know that this is what I would feel before the association was triggered. This can be true as well with the associations we have with human groups.

Can you give a simple demonstration of the power of these associations when it comes to human groups?

Sure. Check out this riddle:

A father and son are in a car accident. The father dies. The son is rushed to the hospital, he’s about to get an operation, and the surgeon says, “I can’t operate—that boy is my son!” How is this possible?

Answer:

The surgeon is the boy’s mother.

Well, duh. When I first heard the riddle, it was a real head-scratcher, but that was a while ago, and I would have thought it would no longer work now. Everyone knows that women can be surgeons.

So I thought. Then I read a study published in 2021 that found that only about a third of college students who had never heard this riddle before gave that answer. The majority of students were either stumped or gave other answers.

the surgeon was a stepfather

the surgeon was an adoptive father

the surgeon was a second father in a same-sex marriage.

“It could be a dream and not reality,”

“While the son was in the operating room he died, and when he saw the surgeon, it was his dad’s ghost.”

“The ‘father’ killed could be a priest, because priests are referred to as ‘fathers’ and members of the church are ‘sons.’”

Presumably, it’s not that university students in the twenty-first century are unaware that surgeons can be women. It’s just that they have an association between surgeons and men, so much so that when they thought of a surgeon, they thought of a man, and entertained outlandish alternatives consistent with this association.

This illustrates the duality between our explicit views (“Women can be surgeons”) and our associations (“Surgeons are men”). And it also illustrates the power of these associations.

How can we explore the associations we have with human groups?

The most popular method was developed by the psychologists Anthony Greenwald and Mahzarin Banaji, with their first article published in 1988. This is the Implicit Associations Test—the IAT. (For a good empirical and theoretical overview, check out their book Blindspot)

To see how it works, you can go here and try it for yourself. Here’s what will happen, using the example of flowers and bugs. You’ll look at your screen as either pictures or words pop up. The pictures are of either flowers or bugs, and the words are either positive (like “good”) or negative (like “bad”). Then, for one set of trials, you will be asked to press one key for either a flower or a positive word and another key for either a bug or a negative word. For another set of trials, it’s reversed: one key for a flower or a negative word and another key for a bug or a positive word. The logic here is that if you have a positive association with flowers and a negative one with bugs, then performance on flower-positive/bug-negative trials will be quicker and have fewer errors than flower-negative/ bug-positive. And this is just what happens.

Want more details? (Is there a phrase meaning the opposite of “tl;dr”?) Here is a longer description, from here:

What is the main finding of IAT studies?

These studies have been done with millions of people and have found that people have negative associations on the basis of race, age, sexual orientation, body weight, disability, and other factors. These effects are present even when questions about explicit attitudes find no bias and are often (but not always) present in subjects who belong to the group that is less favored. The elderly, for instance, tend to have negative associations with the elderly and positive associations with the young.

Have we discovered anything interesting with these methods?

Yes, lots.

One is that our associations have changed over time. In one study, Tessa Charlesworth and Mahzarin Banaji used online data from 4.4 million IATs from 2007 to 2016, focusing on associations regarding sexual orientation, race, skin tone, age, disability, and body weight. They also looked at explicit judgments along these dimensions, asking people to rate on a scale their agreement with statements such as “I strongly prefer young people to old people.”

Looking at explicit attitudes, they found that people have become less biased over time for all of them. The results with associations were more subtle. There was a decline in negative associations in the domains of race, skin tone, and sexual orientation. But there is less of a decline for age and disability and a worsening of associations in the domain of body weight, suggesting that, on an implicit level, we’ve become harsher to those who deviate from “ideal” bodies.

The IAT can also be used to explore the relative strength of different biases. In a study done in 2012, the researchers explored racial bias, using the standard racial IAT, and also explored political bias, using a new IAT that looked at the associations between the symbols of Democrats and Republicans and positive words (Wonderful, Best, Superb, Excellent) and negative words (Terrible, Awful, Worst, Horrible). They found that for the racial IAT, white people favored white people, and Black people favored Black people; in the political IAT, Democrats favored Democrats and Republicans favored Republicans. No surprise. But the extent of the bias was much stronger for politics than for race.

According to the IAT, who gets the most positive associations?

Women. Both men and women have warm and positive feelings toward women, more so than towards any of the usual groups that are studied. There is also a powerful anti-male bias.3

Do implicit associations make a difference in the real world?

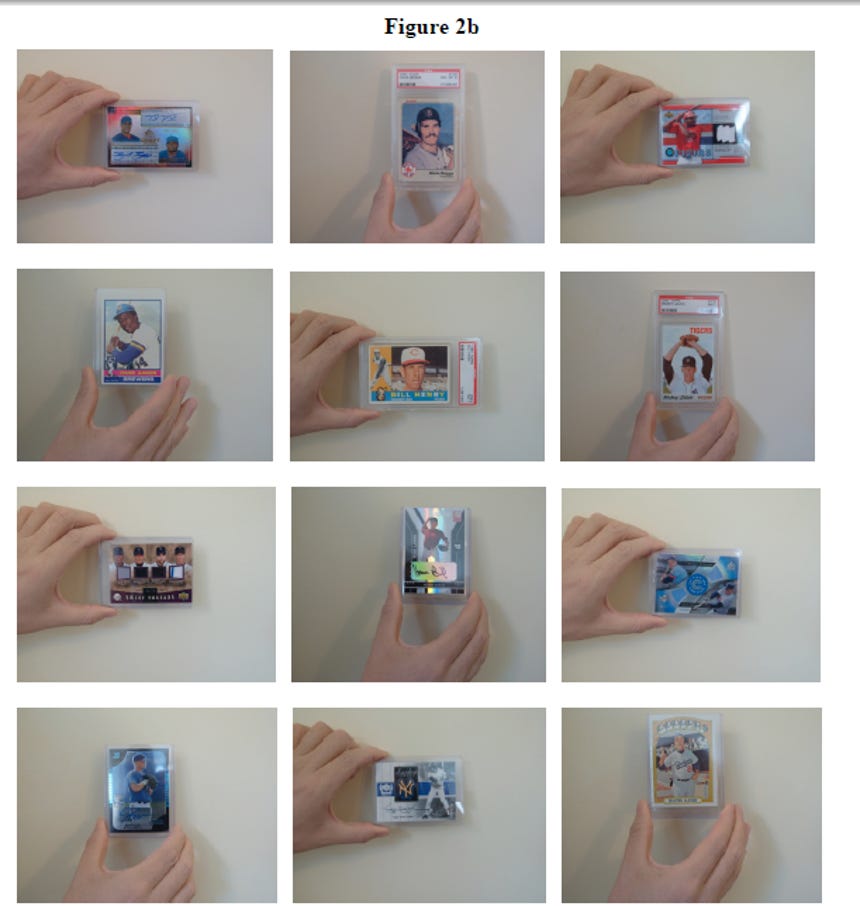

Yes. Here’s a typical study, in which psychologists put baseball cards up for sale on eBay. Sometimes the cards were held by a dark-skinned hand and sometimes they were held by a light-skinned hand, as shown in the figures below. This has an effect: People’s maximum bids dropped about 20 percent for the darker hands.

Now this study doesn’t prove implicit bias. It could be the product of explicit bias on the part of the buyers. Some might have an explicit belief that Black sellers are untrustworthy or an explicit attitude of dislike toward Black sellers that makes them less willing to deal with them. But I bet that some of the bidders in this study have no wish to be biased; in fact, they don’t even know that the study is about race (the hands were interspersed across multiple trials.)

The same influence of positive and negative associations likely occurs in more high-stakes situations, such as when judging job candidates.

Is the IAT a useful test that can find out who is racist?

No.

Before talking about why, you might want to first look at this clip below, from the show “Lie to Me”. This is one of the worst manglings of psychological science I’ve ever seen; it’s worth watching because of its terribleness.

First, there is no racial bias test that involves measuring how fast you are at associating positive words with Barack Obama.

Second, the use of this sort of test to identify whether specific people are racist is a bad idea. And it’s a bad idea that’s caught on—the IAT is sometimes used for exactly this purpose, as in certain diversity training programs. The problem is that the test is too noisy. If you do the IAT online and don’t like how it turned out, take it again—your score will change, sometimes by a lot. Some psychological tests, such as IQ tests or the “Big Five” personality tests, have pretty strong test-retest correlations (reliability); but the IAT has lousy reliability. Your score on the same test taken at different times can vary wildly, so, while there are generalizations that hold across people (you will probably always have some sort of anti-elderly bias), the IAT is not precise enough to use as a measure of how one individual differ from another.

Does implicit bias mean that we are all, in general, racist?

As a reminder, here’s what Garland said:

Implicit bias just means that every human being has biases. That’s part of what it means to be a human being. And the point of examining our implicit biases is to bring our conscious mind up to our unconscious mind and to know when we’re behaving in a stereotyped way. Everybody has stereotypes. It’s not possible to go through life without working through stereotypes. And implicit biases are the ones that we don’t recognize in our behavior. That doesn’t make you racist, no.

I think he’s exactly right. My answer is: No.

I know that people use words like “racist” in all sorts of ways. You might think, as Ibram X. Kendi has argued, that if you are not explicitly anti-racist (which requires activism and engagement with critical race theory), you are thereby racist. Under this definition, most people are racist and would be racist regardless of what their IAT shows. You might also believe that having negative associations with a racial group is sufficient to make one qualify as a racist—and, so, again, just about everyone is racist to some extent or another.

But I side with Garland. I’m not going to try to work through a precise definition, but I think we should retain the meaning of “racist” (and “racism”) in such a way that it’s a bad thing to be racist. We should want racists to change their ways; we should disapprove of racism, and try to fight it within ourselves and others. If someone could respond to the accusation “You’re a racist” with “Of course I am. So are you and so is everybody else.”, well, we’ve lost a useful way to talk about an important issue.

But don’t our implicit biases mean that we carry in our heads actual dislike, even hatred, towards certain groups? Not necessarily. In an interesting series of studies, researchers at Yale explored this issue, hypothesizing that

one reason why White Americans associate African Americans with negativity is that they associate them with oppression, maltreatment, and victimization. Such, negative, yet egalitarian associations could lead many White Americans to associate African Americans with “Bad” on implicit measures of prejudice.

In support of this, they find that people who associate Black people with oppression—hardly the same as hating Black people!—are particularly likely to have negative associations with Black people when tested on the IAT. Do we really want to say that believing that a group suffers from oppression makes one racist towards that group?

The researchers followed up with an experiment: People were taught about novel groups, which were called Noffians and Fasties. Some people were told that the Noffians were oppressed and the Fasties were privileged, and some groups were told the opposite. Then they were given an IAT. As predicted, subjects had negative associations with Noffians in the condition where they were told that they were oppressed. But plainly they themselves didn’t have bad feelings about this imaginary group; they were just responding to what they were told. This sort of thing likely happens with real-world implicit biases.

So what should we do about our implicit biases?

There is often a dichotomy between how we believe we should act and how we actually act. The first arises through reflection and is our considered view as to how we should treat people. The second is influenced by all sorts of less rational forces, including all the associations we carry around in our heads.

For some people, there is no clash at all. If informed that they are bidding more for a baseball card held by a white hand than for one held by a Black hand, they will shrug and say that this is fine. But many of us are at war with ourselves—and we should be.

For one thing, many of our associations are inaccurate. We might be good statistical learners, but the associations we form are often based on idiosyncratic personal experiences and on the sort of media we are exposed to. Garbage in, garbage out. If all you know about Italian Americans is from The Sopranos and the Godfather movies, you don’t have an accurate picture of the world. So too if the associations you have with Jewish people are from your high school reading of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice.

Or try this. Think of the typical American college student. Get an image in your head. Done?

If you thought of a man—and many do—your associations are seriously out of date. For every man in college, there are two women.

Also, in at least some cases, we don’t want to be swayed by our associations with human groups. We want to be fair. People tend to have positive associations with their own racial group, even more positive ones with members of their own political party, and with women. But when choosing who to hire for a job, or who to give an award to, many of us don’t want these associations to influence our decisions.

You might think that the solution here is to try hard not to fall prey to our implicit biases. Perhaps learning about and thinking about our biases can help us overcome them, just through force of will. Unfortunately, the evidence suggests otherwise. We are good at self-justification. We make choices that are shaped by implicit bias and convince ourselves that we are fair and impartial.

My own view is that we do better when we construct procedures that override the biases we don’t want to have. If you’re choosing who to hire and you’re worried about being swayed by your associations, set up a system designed to override them, such as starting the process with the explicit goal of considering candidates from groups that there is a history of bias against. Or set up the system in such a way that you don’t have any distracting information about the people you are judging, as in blind auditions. These are very different solutions—and people have strong views about which is preferable—but the impetus is the same, to engineer processes to eradicate bias where we think that bias is wrong.

This is how moral progress happens more generally. We don’t typically become better merely through good intentions and force of will, just as we don’t usually give up smoking just by wanting to and trying hard. But we are smart critters, and we can use our intelligence to manage our information and constrain our options, allowing our better selves to overcome those biases and appetites that we understand we would be better off without.

Is that enough?

I have a podcast with David Pizarro called Psych, and in one of the episodes (you can listen here), we discuss implicit bias. We cover much of the material above (though it’s not the same—David has a different take on some of these issues than I do). And then we get to the question of what should do to combat implicit bias. I gave my take on overriding our gut feelings.

And then David says something I’m still mulling over, and so I’ll give him the last word here.

Yes, there is virtue in making systemic structural changes for the sake of equity. And if it comes to my own views and my own prejudices, sure, I can't will my way into being less prejudiced.

But what I can do is build relationships with people who are members of the groups that I might have a slightly negative implicit bias against. I think in my own life one thing that has been a salve for my own racism, for my own prejudices, is to connect with certain people and actually love those people and actually care for those people. And then I feel my prejudices kind of simmering away. And I think that this way I become a better person.

So you don't like Mexicans? Go make friends with people who are Mexican. In this way, you will become a better person because you will have exposed yourself to and made yourself care about and love people who you might not have connected to otherwise.

I look at it like this: If you want to stop poverty, the best thing probably to do is to donate to one of many charities. If you're an attorney and you make $500 an hour, work hard and make more money and give it to charity. Sure. But if you want to change yourself, you should volunteer to help out people in your community and actually spend some time with them, I think this will make a change in your life and probably in the lives of those people that would never have come about with a more cold, rational, systemic change. How's that?

Some of this is based on the bias chapter of my book Psych, but most of it is different and I actually end up disagreeing slightly with the conclusions I drew in the book.

Wait, forget about implicit bias for a second. Was Freud right here—are there really unconscious beliefs and desires of that sort? Mental states that are so forbidden that they are somehow locked off from consciousness? That’s a good question, but definitely one for another day.

Note, however, that this is a generalization about men and women in general. One might also ask about the associations we form with intersectional categories, such as young Black women or elderly Hispanic men, and here things get considerably more complicated.

Fascinating, thank you

Hi Paul. I reject the reasonableness of defining an "association" as a bias. Indeed, defining "bias" is pretty tricky. Sometimes, it is mere preference. Other times it is deviation from normative stat model. Yet other times it, it is some sort of systematic error. Yet other times, it is two people judging the same stimuli differently. Associations are none of these things. Associations may predict some of these things some of the time, but: 1. That is an empirical question each time; 2. If A (associations) predict B (preferences, behavior, judgments) then A and B must be different things. Put differently, I associate ham with cheese. To refer to this as any sort of bias (not that you did, but it is an association which you did state is a bias) strikes me as unjustified. Then you get the nasty downstream effects, where by A is amply demonstrated (association) and then simply presumed to constitute some sort of nasty bias (e.g., racial prejudice or stereotypes). Very motte (there is an association!) and bailey (look how racist they all are!).

It then goes downhill from there. Even when associations predict some outcome, it does not necessarily constitute the bailey. Say IAT scores predict discrim, r=.2 or so. This can occur because high racism iat scores correspond to racist behavior, 0 corresponds to egalitarian behavior and negative scores to anti-White behavior. Or it can occur because high "racism" IAT scores correspond to egalitarian behavior and ones near zero to anti-White behavior. For a real example, see Blanton et al 2009 JAP.