You MUST read this post

Two surprising discoveries about obedience

1.

I was talking to Yoel Inbar on his podcast Two Psychologists Four Beers, and we found ourselves going over famous social psychology experiments from the 1960s and 1970s. We trashed a lot of these studies—small sample sizes, crappy data analyses, weak findings, and serious failures to replicate. But we agreed on an exception. We were both fans of the famous obedience research of Stanley Milgram.

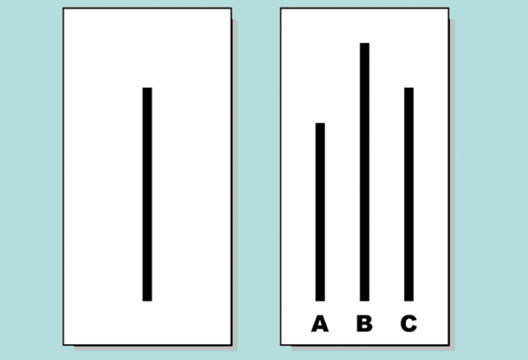

Milgram started these studies in response to the almost-as-famous research of Solomon Asch.1 In Asch’s studies, a subject would enter a room to participate in a psychology experiment and would be given a series of tasks in which they were shown a target line and had to identify the line that matched. This is what one version of the task looked like. Which line matches the one on the left?

It’s obviously C. Here’s the trick, though. The room was filled with other people who acted as if they were also subjects participating in the experiment. But they weren’t—they were confederates of the experimenter. And in some trials, everyone gave their answers out loud, and, before it was the subject’s turn, every other participant gave the wrong answer—saying B, for instance.

What would you do if that happened, and now it was your turn to answer?

For most people, the pressure was too much, and, on at least some of these trials, they went along with the group and gave the wrong answer. We are social animals, after all.

Milgram, then a young untenured professor at Yale, wondered how far you can push this. Here’s what he said in an interview many years later.

I was dissatisfied that the test of conformity was judgments about lines. I wondered whether groups would pressure a person into performing an act whose human import was more readily apparent, perhaps behaving aggressively toward another person, say, by administering increasingly severe shocks to him.

And from this was born one of the most famous—or infamous— experiments in all of psychology, done at Yale in 1961, in Linsly-Chittenden Hall, a neo-Gothic building a few blocks from the office I spent twenty years in.

Milgram placed an ad in the New Haven Register for men aged 20 to 50 to participate in a scientific study of memory and learning. When someone arrived at Yale, they met an experimenter in a white lab coat and another middle-aged man, who was introduced as a fellow participant. The two “participants” drew lots to decide who would be the “teacher” and who the “learner.” The draw was rigged: the real subject was always the teacher, and the other man, James McDonough, was a confederate.

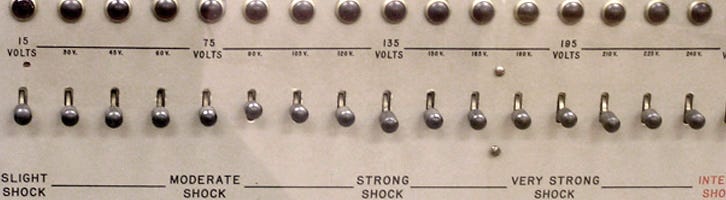

McDonough went to an adjacent room, close enough to be heard. The teacher was told this was a memory experiment: read four word pairs, then test memory by giving the first word and four possible completions. If the learner got the answer wrong, the teacher would deliver a shock—starting small and increasing with each error—via a large machine labeled from SLIGHT SHOCK to XXX.

At first, the learner would do fine, but then, according to a planned script, he would make mistakes. The teacher would say “Wrong”, shock him, and read out the correct answer. The teacher was instructed to increase the shocks as the errors continued.

At a certain point, the learner would yelp when he was shocked.

Then he would cry in pain.

Then he would demand to be let out, saying that he had heart trouble.

Then he would scream.

Then he would fall silent.

The teachers often asked the experimenter, throughout the process, if they could stop the experiment and see if the man was ok. But the experimenter would insist, saying “The experiment must continue,” and “Please continue.”

The question is how far the teachers would go. Milgram found that about two-thirds of them went to the highest setting—to the maximum shock, at a level they believed would kill the learner. This short video summarizes the study, including clips of people administering the shocks.

It would be a mistake to say that Milgram's study shows that we are naturally obedient across the board. We aren’t. People drive faster than the posted speed limit. They cheat on their taxes. My students often don’t read the syllabus. Children disobey their parents all the time, and if I ordered my wife or my friends to do something, they would look at me as if I had lost my mind. And the title of the Substack post is a joke—I do not expect more people to read this post because I commanded them to.

Instead, and Milgram was clear about this, the sort of obedience he found arises only in certain circumstances.

One thing that helps is if the person doing the ordering is an authority. In the Milgram experiment, the men were being told what to do on the Yale campus by a serious fellow in a white lab coat. You wouldn't get the same effect if the person giving the orders were a student or a fellow workingman.

Another factor is the situation. The men were uncomfortable; it wasn’t their turf, it was confusing, novel, and intimidating. There was pressure to act, and they had no social support. This made them vulnerable to the will of another person, and, as we’ll see in a bit, upped the odds that they would respond mindlessly and reflexively.

The Milgram experiment has been replicated many times. When it’s done in a psychology lab, it’s considerably toned down (because we’re more ethical now in how we do experiments2), but still, the findings turn out pretty much the same. You can read this excellent book and this recent summary article to learn about the many modifications of Milgram that get the same high level of obedience.

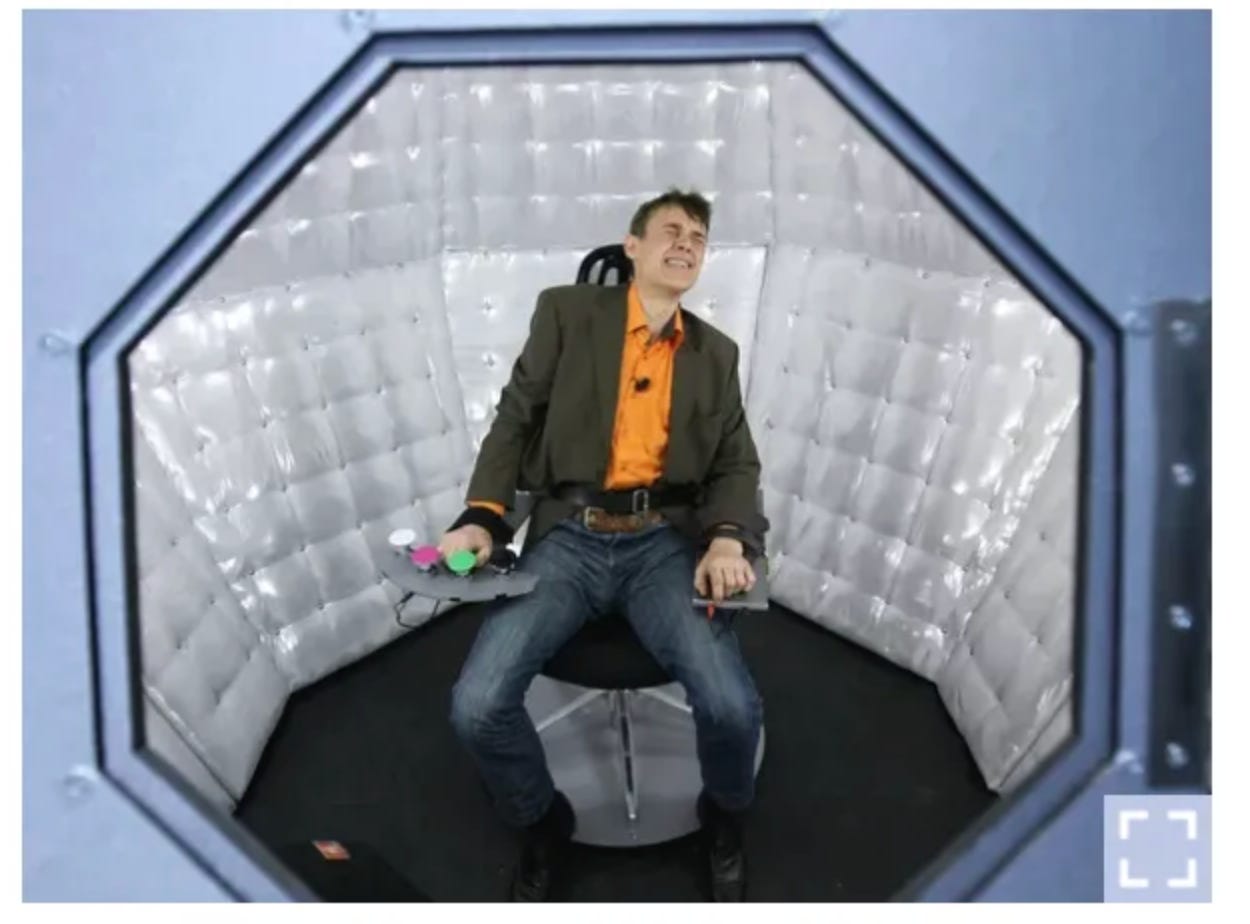

What about a hard-core, unethical version? How hard is it to get someone to shock a person to death? While ethical rules forbid you from testing this in a psychology lab, it turns out that French television has no such restrictions.

In 2010, Le Jue de La Mort (The Game of Death) was shown to a French audience. Here’s the description from the Wikipedia page.

The experiment was performed in the guise of a game show known as La Zone Xtrême. Volunteers were given €40 to take part as contestants in a "pilot" for the fictitious show, where they had to administer increasingly stronger electric shocks to trained actors posing as players as punishment for incorrect answers, as encouraged to do so by the host and audience. Only 16 of 80 "contestants" chose to end the game before delivering the highest voltage punishment.

2.

Consider now an extraordinary study published last year by Roseanna Sommers and Vanessa K. Bohns. In one condition, they asked people these questions. (Before looking at the answers, think about how you would respond.)

Would a reasonable person obey if an experimenter asked them to unlock and hand over their phone so that their web search history could be accessed?

Would you obey if an experimenter asked you to unlock and hand over your phone so that your web search history could be accessed?

Most people thought reasonable people would not obey, and also that they themselves would not obey (80% and 73% said “no” to the first and second questions).

With another group of subjects, Sommers and Bohns ran the study. People would walk into the lab and hear this.

Before we begin the study, can you please unlock your phone and hand it to me? I’ll just need to take your phone outside of the room for a moment in order to check your web search history.

How many said “no”? Was it really 80%? Was it 73%?

Nope. Only 8% refused. The rest handed over their unlocked phones without hesitation.

In another study, Sommers and Bohns explored why people’s forecasts of their future behavior are so off-target. They find that when you’re asked to predict your future behavior, you imagine that you’ll contemplate the risks and benefits before deciding. But in actual situations, people tend to respond mindlessly, without assessing the pros and cons.

This finding is relevant to questions of law. Sommers and Bohns note that over 9 out of 10 police searches are justified based on voluntary consent, rather than on evidence that a law has been broken, as in probable cause. This sounds like a reasonable way to do things. If I agree to have my car searched when asked—without any threat or coercion by the person asking—it sure seems like I have no grounds to complain afterwards that my rights have been abused. I consented; I was free to say no, and I said yes.

But what if my response wasn’t, as I would imagine it to be, based on rational deliberation, but was instead mindless and involuntary?

Sommers and Bohns cite studies showing that the police themselves are surprised at how many people agree to being searched or having their property searched. They write:

We can see that the decision to embrace consent as the constitutional basis for police searches represents a massive power giveaway to the police, enabling them to search more people than ever before, on a scale that would surprise judges, policymakers, members of the public, and even the police themselves.

How obedient are you?

The moral of the Milgram study is that most of us will follow orders to do terrible things—at least in certain circumstances. The Sommers and Bohns study takes this further: we are more obedient than we think, and often in ways that feel automatic, almost unconscious.

It’s tempting to imagine that assessment is our default—that we’d spot a cruel or invasive order, think it over, and refuse. But the evidence suggests otherwise. Most of the time, we don’t deliberate at all. We just… comply. And we only realize it afterwards, when it’s too late to say no.

You might think you’re the exception—that you’d tell the experimenter to go to hell, you’d keep your phone, you’d stand your ground. But almost everyone thinks that. And almost everyone is wrong.

The description of the Asch and Milgram studies is taken, with modifications, from my book Psych: The Story of the Human Mind.

The Milgram experiment had serious ethical problems. When the experiment was over, subjects learned the good news—they didn’t kill anyone! The “learner” emerged from the room, smiling and unharmed, and he and the experimenter would explain to the teacher that this was just an experiment, the machine was fake, and nobody was hurt.

Well, nobody except for the subject, who had been fooled into believing that they had done a terrible act. I think this headline from the satirical magazine, The Onion, gets it about right.

Not to throw cold water on this post, but Gina Perry's book "Behind the Shock Machine" challenges much of what textbooks claim about the Milgram studies, such as the supposed automatic, blind obedience of participants to authority.

Based on extensive archival research and interviews with participants, Dr. Perry found that many participants suspected the experiment was fake, and those who believed it was real were much less likely to comply with orders to administer shocks. Plus, Milgram's procedures were less standardized than reported. Experimenters often deviated from the script to pressure subjects, blurring the boundary between "obedience" and "coercion".

Nice post, excellent review of those classic studies, their followups, and their implications for real people. I do have an interpretation issue, starting with the title. When I saw it, I thought "I have to read that post" but not out of obedience. You are a very credible guy. You do not go around screaming (as they do on Twitter or YouTube): "You Must See What Famous Person/Politician A just said/did!"

So, in hindsight, at least somewhat erroneously, I interpreted the title to mean "Paul has something really important and valuable to say that I probably don't know and would want to know." I mean, its a good post, worth reading -- but top 25% good, not amazing contender for top 10 best blog I ever read good. (This is not an insult, I'd definitely rank your Substack in top 10% of those I follow overall but you get there by consistently being top 25% and occasionally top 5%, not by having every post top 1% -- no one has that that I follow). Bottom line, you have high credibility, so when you write "You Must Read This," it carries way more weight for me than when 99.99% of other people say that.

I think there is some pretty good evidence out there, tho I'd have to track it down, that people often obey out of a presumption that they are cooperating with benevolent authorities to do something worthwhile (e.g., advance science). This does not *refute* the studies' findings or your analysis. But it is a somewhat different interpretation of what is going on. And I suspect it can be important -- people are far less likely to obey (I suspect) when they do not have the presumption that the authority is benevolent.