With Friends Like These

A reaction to some fellow critics of empathy

A couple of weeks ago, I was listening to Ross Douthat interview Allie Beth Stuckey, a conservative Christian writer and podcaster. Then I heard my name.

From the transcript:

Douthat: You wrote a book entitled “Toxic Empathy: How Progressives Exploit Christian Compassion.” You can see just from the subtitle that it is effectively both a critique of secular progressivism and also a critique of your fellow Christians.

I think a lot of people hear a word like “empathy” and think that it is just something that Christians are automatically called to and that a critique of empathy is effectively a critique of Christianity itself.

What is toxic empathy? What is wrong with some forms of empathy, from your perspective?

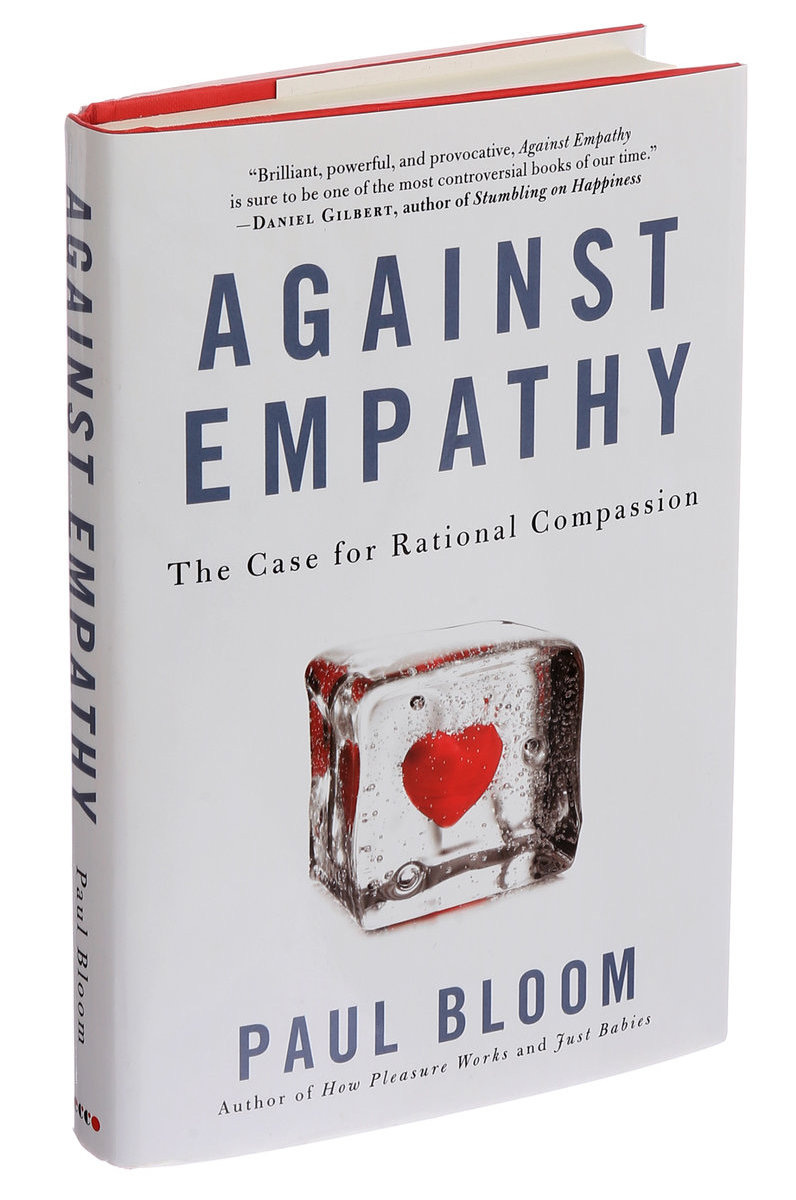

Stuckey: That is correct: some forms of empathy. I argue — and this is not my original argument — I heard Abigail Shrier first say this, and I think she might have even got this from Paul Bloom, a Yale psychologist who wrote a book called “Against Empathy.”

Douthat: An interesting side note is that in fact my own mother once wrote an essay critiquing empathy for First Things magazine some years ago. In it, she drew on Paul Bloom, who is a secular psychologist, criticizing from a secular perspective, an overidentification with other people’s feelings.

All of which is to say I am a somewhat sympathetic audience for this kind of argument.

Stuckey: I just wanted to give proper credit for this first line that I’m about to say: Empathy by itself is neutral. Empathy by itself, I believe, is neither good nor bad. That’s probably not an exact quote from Paul Bloom, but that’s where I got that line of reasoning.

The next day, I was contacted by Jennifer Szalai, who interviewed me for an article on the recent attack on empathy by Stuckey and others.

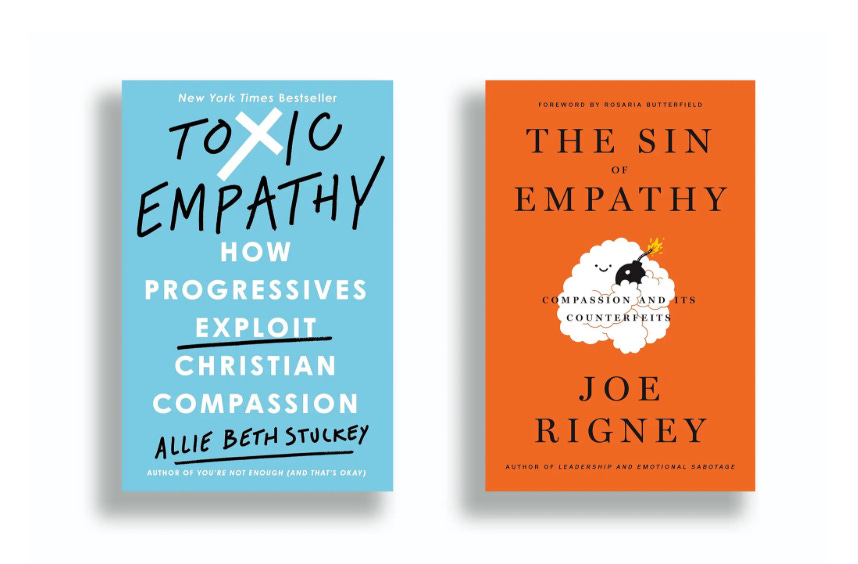

Szalai discussed new books by Stuckey and by Joe Rigney.

In their books, Stuckey and Rigney start out insisting that they’re not trying to stamp out empathy per se — they oppose only “toxic” (Stuckey) or “untethered” (Rigney) versions, which trick Christians into tolerating abortion access and gay marriage. Giving the example of a 12-year-old raped by her stepfather, Rigney says that granting her request for an abortion is an example of the “empathetic myopia” that fuels “the culture of Death.” Stuckey says that as much as she feels sorry for the undocumented Mexican mother detained by ICE after 14 years in the United States, “Scripture depicts walls, both literally and metaphorically, as a defense against disorder and evil.”

It’s not just conservative Christians who are critical of empathy these days, Szalai notes. It’s also billionaire edgelords.

In February, when Elon Musk went on Joe Rogan’s podcast, Musk derided Democrats for succumbing to “suicidal empathy.” Caring about others, the men agreed, had gotten so out of control that it was becoming self-destructive. “The fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy,” Musk said. “They’re exploiting a bug in Western civilization, which is the empathy response.”

I’m not sure how much I’ve influenced these ideas. I hope I haven’t. My moral views are very different from those of Stuckey, Rigney, and Musk, and I think that many of the policies that these individuals defend are awful. Listening to Stuckey talk about Against Empathy is like listening to an interview with Jeffrey Dahmer and hearing him say that he was inspired by a cookbook I wrote.

But I do think Stuckey gets a lot of things right. She presents this example to Douthat.

If you take the abortion issue, I start out by telling the story of a woman named Samantha.

Her story was first told by NPR. She found out that her baby had a fatal fetal anomaly at the 20-week mark, but in Texas she wasn’t allowed to abort her child. NPR tells the story as if this was horrible for Samantha, who had to go through the financial, physical, emotional burden of bearing this child, only to have this child to die.

By the end of the story, the reader feels exactly how it seems NPR wants them to feel, which is that this is a great injustice toward Samantha. How dare these draconian laws force her to do something so painful, so financially burdensome. We need to liberate women from these anti-abortion laws that are making them go through so much.

You have so much empathy for Samantha that you support the pro-abortion position by the end of this, through the mode of storytelling.

Stuckey goes on to complain that this is a cheap argument against the Texas law. I agree with her. Certainly, Samantha's suffering should carry weight. In the absence of any other consideration, her terrible experience is a powerful argument against the law. But every large-scale policy is likely to cause serious harm to some people, and so focusing on a single case is more of a rhetorical move than a reasoned argument.

This might be hard to see in this example if, like me, your heart is already set against this anti-abortion law. So let’s change the sort of empathic argument we’re looking at. The following is from an article I wrote over ten years ago, before a certain real estate mogul rose to public office.

Politicians are comfortable exploiting this dark side of empathy. Donald Trump likes to talk about Kate—he doesn’t use her full name, Kate Steinle, just Kate. She was killed in San Francisco by an undocumented immigrant, and Trump wants to make her real to his audience, to make vivid his talk of Mexican killers. Similarly, Ann Coulter’s recent book, Adios, America, is rich with detailed descriptions of immigrant crimes, particularly rape and child rape, with chapter titles like “Why Do Hispanic Valedictorians Make the News, But Child Rapists Don’t?” and headings like “Lost a friend to drugs? Thank a Mexican.” Trump and Coulter use these stories to stoke our feelings for innocent victims, to motivate support for policies against the immigrants who are said to prey upon these innocents.

If you want, you can read what happened to Kate Steinle here, or read here about the tragic death of Laken Riley, raped and murdered by an illegal immigrant. You can also look at their faces—this often helps intensify one’s empathic response.

There is something wrong with anyone who is unmoved by the death of these women, and I assume that few of the readers of Small Potatoes are moral monsters. So does this seal the deal? Have you now been convinced that Donald Trump is right in his aggressive policies towards illegal immigrants?

I hope your response here is that this is a bullshit argument. You don’t make policy decisions based on heart-wrenching tales.1 But if it’s a bullshit argument to trot out our Steinle and Riley in support of an anti-immigration law, it’s just as much a bullshit argument to trot out Samantha to attack an anti-abortion law. In her conversation with Douthat, Stuckey puts it nicely.

Ultimately, and this is really my argument in the book, there are always going to be people on both sides of any story with real pain, with real stories that matter.

But this is where my agreement with Stuckey ends.

One concern I have is that her critique of empathy is inconsistent. She is a fierce critic of empathic arguments by progressives, but she’s happy to trot them out for her own side.

Right after she explains that we shouldn’t fall for the story of Samantha, who went through terrible suffering because of this Texas law, she tells us this:

They [liberals] don’t want you to think about the actual victim of abortion. What would have been the fate of this baby, whose name is Halo? What would have been her fate if Texas had not had this — quote, unquote — pro-life law? She would’ve been poisoned. She would’ve been dismembered. She would’ve been discarded like toxic waste.

But instead, she was delivered and clothed and named and held and loved and buried like the full human being that she is.

Now, maybe I’m being unfair. Maybe Stuckey was making a point to Douthat: Look, I’m going to make the opposite empathic argument here, this time on the side of the baby; I hope the obviously manipulative nature of my Halo story will help your liberal readers see how illegitimate such appeals are.

Maybe, but I don’t think so. Later in the interview, she trots out exactly the same sorts of stories that Trump used to attack illegal immigrants.

Stuckey: …. they’ll never talk about Kate Steinle or Laken Riley or the stories on the other side of it.

Douthat: And the stories on the other side are stories of Americans who have been murdered or assaulted by illegal immigrants.

Stuckey: Yes. I forget the New York Times audience might not just know those stories automatically and those names.

The frustration she expresses here—why aren’t liberals more familiar with these well-known stories of immigrant crimes?—makes me wonder about her consistency as a critic of empathy.

One last point about consistency. Stuckey thinks moral decisions should not be made by appeal to abstract rights or by weighing costs and benefits. Moral decisions should be made by reading the Bible. But, as she concedes, the Bible doesn’t give clear guidelines about immigration. This made me curious as to how she would answer this question.

Douthat: Is there something that Donald Trump could do on immigration policy that you would consider evil?

Stuckey knows a lot more about the Bible than I do, and I wondered which Biblical principles would clash with extreme anti-immigrant policies. Perhaps she would express concerns about the separation of families, or talk about a moral imperative to care for refugees from repressive regimes. But, no, she said this.

Stuckey: I am most sympathetic when it comes to the taking in of Christian refugees from the Middle East and elsewhere. I want these people to be protected. My highest priority is the protection and the preservation of Christians, especially persecuted Christians. The stories that I’ve seen about Christian refugees from war-torn areas having a difficult time coming to the United States are the most difficult for me.

This isn’t principled moral reasoning, and it’s not religiously grounded. It’s just tribalism. I want Trump to make an exception for people like me.

I’ll end with a word about Musk.

Earlier this year, the White House posted a video of immigrants in shackles being prepared to be deported. The heading they gave to the post said “ASMR: Illegal Alien Deportation Flight”, where ASMR, or “Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response,” refers to a pleasant feeling some people experience when hearing certain sounds.

Elon Musk found this funny.

As I said, I don’t think one should decide complex issues by zooming in on the suffering of specific individuals. One can support an immigration policy while knowing that it will cause real harm to some people, because any policy will have such an effect. But of course, concern for the suffering of people is foundational to morality; such suffering is something we should always try to minimize.

It’s hard to see in Musk’s reaction a real concern that empathy will lead people astray, leading to greater overall harm. It looks more like a general indifference to (or worse, amusement from) the pain of certain others. When Musk complains about ‘suicidal empathy’, I don’t think he’s worrying about the failure to apply consistent moral principles. It’s just a fancy way to say that some people aren’t worth caring about.

Szalai was kind enough to give me the last word in her article.

… Instead of critiquing empathy as a tool for moral reasoning, anti-empathy warriors seem intent on obliterating any shared sense of common humanity.

I called Bloom to ask what he made of this development. He distinguished “Against Empathy” from “near neighbors to my view which are just calls for cruelty and bias.”

“My book is a call for compassion, kindness and the ways in which empathy can get away from that,” Bloom said. He added, “I worry that some people think, for whatever reason, ‘I don’t want to care about immigrants,’ or ‘I don’t want to care about Africans.’ And so what they say is, ‘Well, I hear empathy is bad. So I guess that justifies me not caring.’ But that’s a terrible point to make.”

Yes, stories about suffering can lead people astray. But such suffering matters; one shouldn’t delight in it.

Against Empathy goes on to enumerate many other problems with empathy. It is too unreliable and arbitrary to form the basis for policy judgments; it’s innumerate, parochial, and biased. The stories of Steinle and Riley illustrate this—they are especially moving to many Americans because they are attractive young white women, but, upon reflection, most people would agree that this fact shouldn’t carry special moral weight.

This is an expected development. People will always distort and weaponize things to justify whatever they wanted in the first place. Kahneman taught us the concept of cognitive bias and then people started accusing their opponents of bias while ignoring their own biases. Popper taught us that tolerating those who use literal violence to advance their ideas can lead society to a dark path (the paradox of tolerance _ the original version is wildly different from the modern conception), and now people use that as an excuse to censor and cancel people they don't like, while calling violence when the same happen to them. And then Bloom taught us to be skeptical of empathy and now people use it to dismiss things they opponents want while still abusing empathetic discourse themselves.

Excellent nuanced view.