Why I use trigger warnings

Kiss, kiss, bang, bang

A long time ago, I was living in London and going to a lot of plays. One Saturday night, I ended up at one where the website had warned (or promised) that there would be “full frontal nudity” and “explicit sexual activity”. The play was engaging enough, but I couldn’t help noticing that as we got to intermission, there wasn’t any nudity or sex. Actually, there wasn’t any sign that anything like this was in the offing. Maybe the tone would shift in the second half? But it didn’t, and as we were coming to the end, I felt a mix of anticipation and anxiety—was the big finish going to have the main characters stripping off and banging? Nope, nothing. Walking out, I asked my partner: “Did we miss it?”

It turned out that I was mixed up. The warnings were for a play that we had planned to see but had been sold out. But I’ll tell you, this state of expectation did make me experience that evening in an entirely new light. I probably enjoyed it a lot more.

Sometimes warnings entice. Advertisements for horror movies often make a big deal about how they are not for the faint of heart. A recent gory flick had the clever gimmick of distributing vomit bags before the showing.

But, more typically, warnings allow people to avoid experiences (I’m going to pass on Terrifier 2 myself), or prepare psychologically for them, or decide whether they are suitable for their children.

When they are used in classes, we call them trigger warnings.

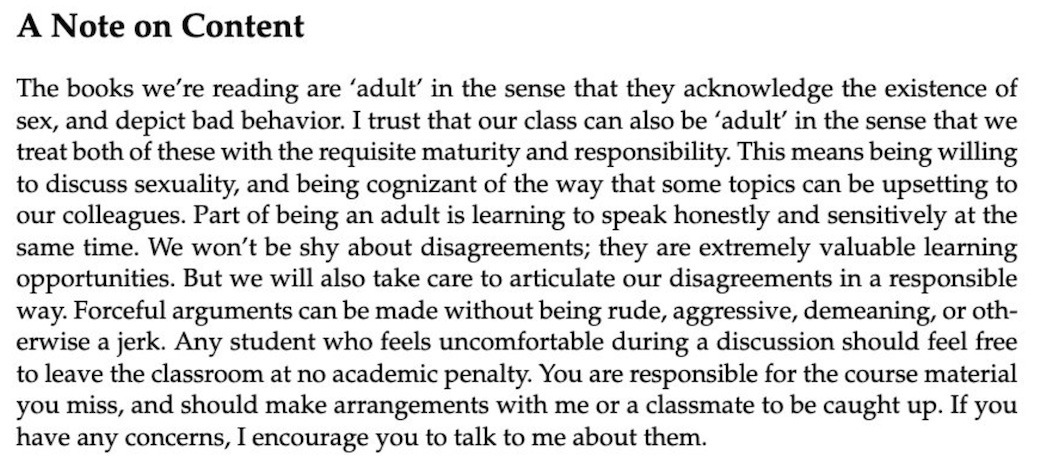

Many of my friends are against trigger warnings, but I like them and I use them. Here’s one of mine, from the syllabus for a seminar on moral psychology that I’m now teaching, available to students before they decide to sign up for the course.

Here’s another one I like, from the philosopher Mason Westfall (used with his permission.)

I also sometimes give verbal warnings in class, telling students what to expect about certain readings we are going to discuss the following week. I do so, for instance, before students read an excerpt from David Livingstone Smith’s excellent book “On Inhumanity”, which contains, among other things, gruesome descriptions of lynchings.

The typical argument in favor of trigger warnings evokes the language of trauma and PTSD, as with this article in the New York Times by the philosopher Kate Manne, a scholar whose work I greatly respect. The typical argument against trigger warnings, like this one by my friends Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, argues that these concerns are hyperbolic and overblown, and that, in fact, trigger warnings can be harmful to students, encouraging hyper-sensitivity and fragility.1

If you frame the debate this way, the evidence favors Lukianoff and Haidt. This recent study is typical, concluding, “trigger warnings are not helpful for trauma survivors.” Some of the studies have different results— if you want to delve into the literature, here is a good place to start—but it’s fair to say that there is no good evidence for the psychological benefits of trigger warnings.

But I am pro-trigger warning for reasons that have nothing to do with worries about trauma or PTSD or psychological health.

I am in favour of them because of norms of civility and respect. Students are students, but they are also people, and should be treated with consideration. When they choose what courses to take, they deserve an honest description of what the course will involve. Shouldn’t people be as informed as possible before making a decision?

Suppose I knew a gentle soul who was considering watching the television series Outlander, having heard that it’s a beautiful historical romance. I might inform them that, yes, lots of romance, lots of history, very pretty, good acting—but it also contains a lot of graphic rape scenes (like a lot). This is useful information that would help my friend make a choice (they might treat it as a negative, a positive, or irrelevant), and (with the important exception of spoilers) what’s wrong with providing useful information? Isn’t that a kind thing to do?

And when someone is about to read something or watch something that’s likely disturbing in an unexpected way, it’s just good manners to give a heads-up. Would you say to a friend, hey check this out, and then hold your phone out to them and show some terrible act of animal cruelty? Well, if so, I’m sorry for your friends. They’d probably appreciate some warning. Even if it’s something that they have to experience, and there’s no opting out, people want to be able to prepare themselves.2

Sometimes the case for not giving trigger warnings is framed in terms of “exposure therapy”, building up resilience, and so on. But I’m not a sergeant in the Marines, a therapist, or a parent who is concerned that their child is becoming a snowflake. I’m a university professor. My job is to educate, not to toughen people up.

This is probably my least controversial view. (If I’m wrong, let me know!)

My sense is that many of the people who claim to be against trigger warnings wouldn’t disagree with what I say above. Rather they are against something more specific.

They might be against what you can call stupid trigger warnings. It is silly, I agree, to warn students before talking about Donald Trump, climate change, or divorce. In a New Yorker article a few years ago, Harvard law professor Jeannie Suk Gersen writes

One teacher I know was recently asked by a student not to use the word “violate” in class—as in “Does this conduct violate the law?”—because the word was triggering.

That’s silly. If you find the English verb “violate” upsetting, it’s your problem, not the professor’s. No trigger warning for you!

Critics of trigger warnings might also be thinking of mandated trigger warnings. If so, I agree with them. There are limits to what a professor is allowed to do in class, but this isn’t one of them. Along with Manne, my fellow defender of trigger warnings, I don’t think they should be forced.

Let’s consider now a more contentious issue. Should students be allowed to opt out of material that they find too upsetting? In the same New Yorker article, Gersen talks about the fears that her colleagues have about talking about rape.

Some students have even suggested that rape law should not be taught because of its potential to cause distress. … About a dozen new teachers of criminal law at multiple institutions have told me that they are not including rape law in their courses, arguing that it’s not worth the risk of complaints of discomfort by students. Even seasoned teachers of criminal law, at law schools across the country, have confided that they are seriously considering dropping rape law and other topics related to sex and gender violence. Both men and women teachers seem frightened of discussion, because they are afraid of injuring others or being injured themselves.

Gersen makes a case that rape law is an essential part of legal training. If so, then—while it should be discussed with care and sensitivity—students need to know this stuff, and it should not be excised from a criminal law course. The same point applies to other sensitive domains; it is unpleasant for many of us to talk about child abuse, lynchings, or torture, but education often requires confronting difficult things.

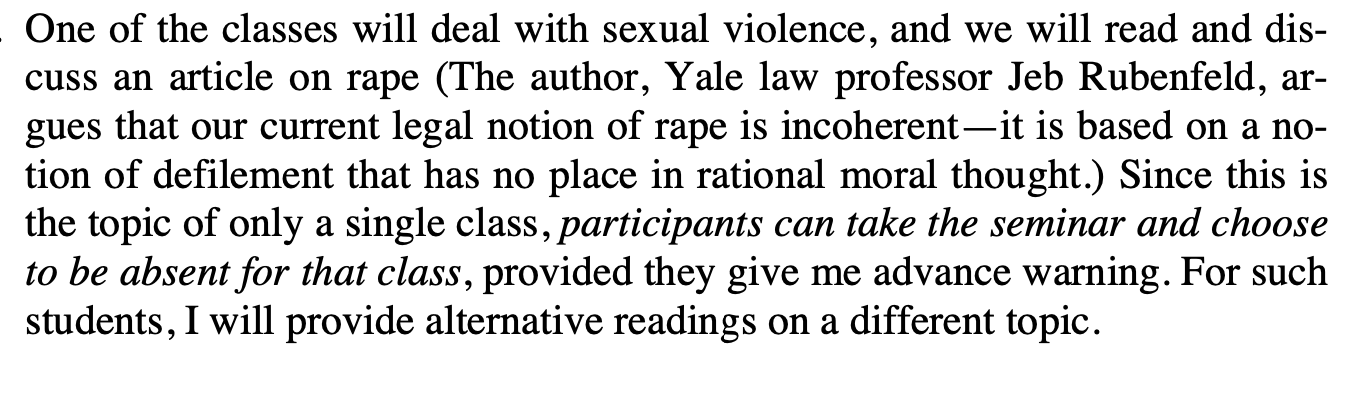

My views have changed here. In a moral psychology seminar several years ago, I assigned a fascinating article by Jeb Rubenfeld called The Riddle of Rape-by-Deception and the Myth of Sexual Autonomy. As you might guess, it’s all about rape. I decided to make the class optional, writing this in the syllabus:

Nobody opted out and we had a perfectly good conversation. And I now think that offering the option was a mistake. There is nothing gratuitously graphic in Rubenfeld’s article, and debates over consent, autonomy, and defilement are good topics for a moral psychology course. If I assign it again, I’ll give the usual trigger warning for students considering taking the course—but leave it at that.

These articles are eight years old, when the debate was really raging. So, yes, I’m a little late to things.

Here’s a joke that nicely makes this point:

A man is on vacation and his brother is taking care of his cat. The man calls his brother to check in and asks, "How is the cat?" The brother says, "The cat's dead." The man is distraught. He says, "You can't just tell me like that. You have to ease me into it. The first day, you tell me the cat's on the roof and you can't get her down. The second day, you tell me the cat fell and she's in a coma. Then on the third day, you can tell me the cat died." The brother apologizes profusely. Then the man says, "It's ok. Don't worry about it. How's mom?"

The brother responds, "Mom's on the roof and we can't get her down."

interesting! wouldn't a "middle way" be to just call it "note on content"? I think the word "trigger warning" presupposes ppl will be triggered and I personally find it a bit childish for that reason. Content Note would be a bit more neutral. I must say I believe in the idea that exagerating the potential of harm in everyday discourse is making us less psychologically resilient, so I am coming from that kind of direction

Hi Paul, big fan of your work.

It’s an interesting argument, but you seem to be defending a weak version of trigger warnings. In my mind, the debate was never about whether we should warn people about content that’s universally distressing (e.g., “hey look at this photo of a severed head”). I think it’s often useful to give people information about content, as you do in your syllabus, and I don’t think many anti-trigger warning folks would disagree. For example, no one’s seriously arguing that PG-13 labels on movies are coddling kids.

I think the more interesting debate is whether it’s helpful to 1. Warn individuals with PTSD about potential reminders of their trauma and 2. Warn individuals with no trauma history about potentially distressing (ambiguous but plausibly upsetting) content. In both cases, a trigger warning doesn’t just tell someone what they’re going to encounter but that it could trigger an intense negative emotional response.

Ultimately, whether or not trigger warnings are common courtesy should be premised on whether or not they’re effective. (If you try to help someone but end up doing nothing, or making things worse, you’re not doing them a service). I think there’s good evidence that trigger warnings are unhelpful for individuals with PTSD, as you allude to. I also think there’s good reason to suspect that they’re unhelpful in the second usage. For example, my colleagues have a cool new paper showing that content warnings decrease the aesthetic appreciation of art (DOI:10.31234/osf.io/6h5k8). The same argument has been made against warning people about distressing themes in literature: Telling people how they’re likely to react to difficult content draws their attention away from other themes they could have appreciated/learned from and might just make them distressed when they otherwise wouldn’t have been.

Of course, there’s another way that trigger warnings could be ‘effective:’ they could signal respect and support to students. Or they might just signal the professor’s ideological alignment and compromise their epistemic credibility. Who knows - some of my colleagues and I are prepping a study that will look at the interpersonal signals that trigger warnings send.