Why are so many professors conservative?

Two theories

About ten years ago, I was co-chair of the Dean’s Committee on Online Education at Yale.1 Our primary mission was to explore making some of Yale’s classes freely available to students worldwide by creating MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses).

I thought this was a fantastic idea. Giving away our best courses to people who would otherwise have no access to university education seemed like just the thing a great university should do. I also saw the rise of MOOCs as poised to revolutionize higher education in North America. Some of Yale’s best professors were lined up to teach these courses, including the physicist Ramamurti Shankar, the psychologist Laurie Santos, and the Nobel laureate economist Robert Shiller. Few professors at American universities can teach as well as these scholars, so wouldn’t it be wonderful if their lectures were available to students everywhere?

The committee decided to proceed with the plan, and I volunteered to present its recommendation at a meeting of senior faculty.

It did not go well—I got my ass handed to me. Many of my colleagues hated the idea. They said that free open classes would dilute the value of a Yale education. It would endanger their jobs and those of their students. There were strong feelings expressed, and a bit of yelling.

The committee met after the meeting, and I remember an Associate Dean looking at me sympathetically and murmuring, “Well, this isn’t really the sort of thing that requires a faculty vote.” So we just did it.2

Nobody talks about MOOCs anymore. Like professors everywhere, my colleagues and I are now obsessed with AI.

Universal access to LLMs poses problems that we can’t duck. How can we keep assigning reading responses and take-home essays when every student has access to LLMs that can do their work for them in seconds? (Despite all of the talk of AI slop, the finished product is typically hard to distinguish from good student writing.) I’m teaching a freshman seminar this semester, and I’m struggling to figure out how to assign work that most of the students won’t cheat on.

On balance, though, I am excited by the rise of the machines. Putting aside all the ways LLMs have helped my everyday life—including dealing with bureaucracy, offering advice on home renovations, and providing feedback on medical reports for elderly relatives—they have made my work life better in countless ways. It’s not just that ChatGPT can quickly handle many of the bullshit tasks that fill a professor’s day. It can, in ways I’m just coming to understand, help me as a scholar and researcher. I use it to brainstorm ideas, provide critical feedback on my papers, and write extended summaries of research areas. It has taught me a lot—I’ve got a lot of mileage out of the command: “Explain such-and-so to me like I’m a 10-year-old”. ChatGPT is becoming more and more like a sycophantic, erratic, and occasionally brilliant research assistant; maybe one day it will be a collaborator.

I’m not really a tech guy, and much of my pedagogy, mentoring, and research can be charitably called “old school”. So I wouldn’t have thought I’d be ahead of the curve here. But I am. It’s such a surprise to me how few of my colleagues share my enthusiasm. If you go on academic Bluesky and say anything positive about AI, you’ll get slammed. I have attended meetings where other faculty members with far more technical chops than I’ll ever have proudly announce that they refuse to learn how to work with AI. More than one prof I know has said that they would ban it if they could.

This reaction reminds me a lot of the reaction to MOOCs years ago. And this makes me wonder: Do professors fear the future? Are we anti-innovation?

Now that would be a hell of an extrapolation to make from two anecdotes. A more charitable interpretation—one that I bet many readers will have settled on—is that profs know bad ideas when they see them. Maybe MOOCs were a mistake; maybe AI is a genuine threat to education, science, and scholarship, and professors are sharp enough to appreciate this. Rejecting dumbass ideas isn’t fearing the future; it’s just being smart.

Well, maybe. But I think there is something going on here that’s a lot broader than MOOCs and LLMs.

Imagine being an American undergraduate in the 1980s and suddenly zapped by a time machine into the present. Things are different! There are a lot more women. It used to be about fifty-fifty; now, colleges and universities are about 60% female. In 1980, non-White students accounted for under one-fifth of undergraduates; now they’re roughly half. There are technological changes. Assignments, syllabi, and readings will be posted “on the web”; lecturers will use “PowerPoint”; people will sometimes say “Let’s meet over Zoom”. You’ll be pleased to discover grade inflation—it’s a lot easier to get an A.

But most of the life of an undergraduate will be similar. The popular majors have shifted a bit (interest in education has dropped; now there’s computer science), but the big picture is largely unchanged—students tend to cluster into business (by far the largest major), economics, psychology, and the humanities. The graduation requirements for these majors are often pretty much the same. And, just as in the 80s, you’ll go to lecture halls for introductory classes, attend labs if you’re a science student, and take smaller seminars as a junior or senior (if you’re lucky enough to get into them). You’ll do the same sorts of take-home reading responses, essays, and problem sets, and you will take the same sorts of exams (multiple-choice, short-answer, etc.).

If you were a time-travelling graduate student, you would notice hardly any difference at all. In the 80s and in the present, you’ll attend seminars, suffer through qualifying exams, meet with your committee, meet with your advisor, work in a lab (sciences) or spend time in the library (humanities), and go through various hurdles to get your PhD.

And what if you were a faculty member? You’ll be sad to discover that it’s still publish-or-perish. There’s the same academic hierarchy. Assistant Professor, then Associate Professor, then Full Professor, with Adjunct Professors still being exploited and doing much of the work. Your day will include writing letters of reference, meeting with students, flying to conferences, spreading malicious gossip, and attending faculty meetings.

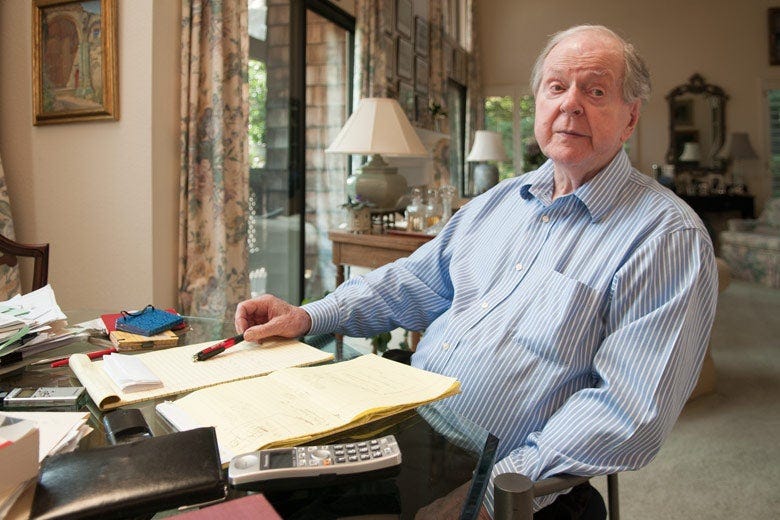

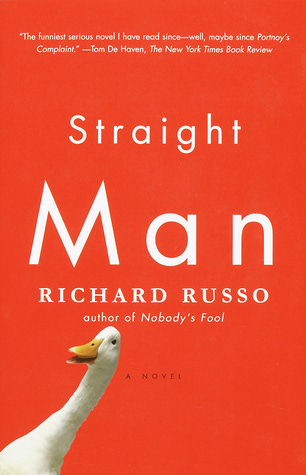

I love campus novels (see here for a list of my favourites), and one of the best is Straight Man. This was published in the late 90s, and, rereading it now, it could just as well have been written last year.

Most of the changes that occurred, such as shifting demographics, were beyond professors’ control. (The interesting exception is grade inflation.) And most of what remains the same was within our control. We remain in the world of the 80s, I believe, because this is just the way we professors like it.

#NotAllProfessors, of course. It’s professors who thought up the idea of MOOCs; some professors, such as Tyler Cowen and Ethan Mollick, are bullish on AI, more so than I am, actually. But they are a minority. At least in the humanities and social sciences, the fields that I’m most familiar with, professors are wary of change.

It turns out that there’s a word for people who feel like this. In his mission statement for the National Review, William F. Buckley described a conservative as

someone who stands athwart history, yelling Stop!

Most professors are conservatives.

Is this conservatism a bad thing? It depends on whether the past is worth conserving. My own view is that we are often right to be conservative. As one example, seminars are a wonderful institution; they’ve been around at least since Socrates, and there’s every reason to keep them. Administrators sometimes chafe at their expense—it’s not efficient, they will tell us, to have a prof sitting with a dozen students instead of teaching hundreds. But professors are right to insist on their value. Another example is tenure; I strongly support the protections of tenure and have no patience for the Republican radicals who want to get rid of them.

But there are all sorts of things about the university that we should have radically transformed. The softest target here is lectures. In a world with laptops and Zoom, would you cram 500 students into a lecture hall for 60-90 minutes to watch a professor stand on a stage and show slides? Is this the best we can do? Whenever I talk to professors who teach large lecture classes, their biggest complaint is that students don’t show up. My sympathies are with the students. If we are going to have lectures at all (and this is hardly obvious), why have students schlep over to campus at 9 AM to watch them on a hard seat in an auditorium? Why not record them and let the students watch them whenever they want? Actually, if we’re going to do that, why do the lectures have to come from a prof on campus? Why not have them presented by the best professors in the world—in other words, why not MOOCs?

My point here isn’t to convince you to throw your support behind online courses—it would need a much longer discussion to make this persuasive. My point is that this isn’t a conversation anyone is having. And this is because professors are too conservative to explore alternatives to the usual way things are done.

Everyone knows professors aren’t politically conservative. We are famously more progressive than the rest of the population, more prone than average to favor more liberal political parties—in some departments at Yale, for instance, Democrats outnumber Republicans by a ratio of 78 to 1. Now, being a Democrat is weak sauce, but professors are also more likely than most people to hold truly radical views and to endorse sweeping social and political change.

We are also radical in our ideas—we often shock the world by rejecting received views on religion, gender, the family, and morality. And, more generally, while a time-travelling student or faculty member will find little of the university's life has changed, he or she will notice immediately that the content of what is studied and taught is profoundly different. The ideas explored in a lab meeting or seminar discussion now will have little overlap with whatever was happening in the 80s. Professors are not, in general, stuck in the past.

It’s interesting, then, that the only aspects of our lives where we abandon our bold thinking and our enthusiasm for radical changes are those that matter the most to us.

I think there are two reasons for this.

The first is from the historian Robert Conquest (His “First Law of Politics”).

Generally speaking, everybody is reactionary on subjects he knows most about.

In his 1991 Memoirs, Kingsley Amis recounts a conversation with Conquest, in which Conquest used Amis’s views on education as an example of this generalization.

he [went on] to point out that, while very ‘progressive’ on the subject of colonialism and other matters I was ignorant of, I was a sound reactionary about education, of which I had some understanding and experience.

Conquest was conservative himself, and his point was that conservatism is the smart default; radicalism is often grounded in ignorance. We are conservative about what we know best because we appreciate the value of the traditional ways of doing things and are sensitive to the risks of giving them up.

I’ll put myself up as an example here. I have a lot of ideas about how to improve the Supreme Court, the training of medical students, and the making of Hollywood movies, but I have to concede that my enthusiasm for radical change might be in part because I don’t understand these institutions very well.3 Conquest would say that if I were better informed, I would have a clearer understanding of the value of the status quo and a better appreciation of the drawbacks of some of my radical ideas. I’d be more conservative.

There’s a professor friend of mine who is very politically left and very pro-union. He wouldn’t cross a picket line if his life depended on it, and he has fought for workers' rights to unionize. There’s just one case where he’s anti-union, and I bet you can guess what it is. Graduate students at his university. He offers sophisticated arguments that graduate student unionization is a mistake, that students aren’t employees in the relevant sense, and that a management-worker dynamic would damage the special (perhaps even sacred) relationship between students and advisors. He may or may not be right, but, regardless, it’s a nice example of how everybody is reactionary on subjects he knows most about.

The second reason we are so conservative is less respectable than Conquest’s First Law. It’s not about expertise; it’s about skin in the game. If you have a lot invested in a system, you won’t want it to change. Asking a prof about AI is like asking a taxi driver to weigh in on Uber. I think I have good reasons for my (conservative) defense of tenure, but you’d be forgiven for assuming that, having worked for and benefited from the protections of tenure, I don’t want them taken away. Part of professors’ unwillingness to give up on lectures is that they take a long time to prepare—once that time is invested, we don’t want to start anew. We certainly don’t want to transform the university in a way that risks making us obsolete. Upton Sinclair put it nicely:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.

This second consideration—self-interest—explains why some things do change. These are the cases where the changes are painless. Turning Cs into Bs and Bs into As is no work at all, so once there was sufficient pressure to do so (from students and from promotion committees who care what the students have to say), grade inflation was an easy decision. Other changes, such as restructuring the university hierarchy, giving up on or transforming lectures, and dealing with AI, are considerably more threatening to our way of life, so it’s natural that we balk at them.

If this analysis of academic conservatism is right, it’s very general. These considerations apply to anyone in a field; to anyone with skin in the game. It applies to soldiers, lumberjacks, State Senators, priests, basketball players, and tax accountants—all are predicted to be conservative about what they know best and what matters most to them.4

If this is true, one thing follows. When things do change—for better or for worse—it won’t be the professors who are pushing for it. It will come from the outside, from legislatures, donors, and parents. Like all good conservatives, professors will fight for the status quo.

I recently wrote a post called, Why are so few professors trouble-makers? (reprinted in the Chronicle of Higher Education as Why aren’t professors braver?), So I guess I have a series going on here. Thanks to Yoel Inbar, Mickey Inzlicht, and Christina Starmans for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

The parable of Chesterton’s Fence is relevant here.

Yoel Inbar pointed out a professor-specific factor that complements the two theories here—academics tend to be risk-averse (see also my post "Why are so few professors trouble-makers?"). Among other things, he observed that being a tenured professor is an unusually secure job, which appeals to people who want security and are willing to give up salary and other benefits to get it.

Students who schlep in for a 9 am lecture also have skin in the game! Commitment to the task, motivation, perhaps the all important desirable difficulties in learning, even a smidge of cognitive dissonance (why did I get up so early? Oh, yeah, I'm here to learn!), meeting their friends and colleagues, a quick q to the prof, signalling of their commitment to a collective endeavour, using a learning structure they are unable to impose on themselves, and so much more.

Attentional engagement in a zoom lecture is pretty poor. And students hate them!

In person set piece lectures working through a deep curriculum are valuable in their own right. And they're not easily transferable once you get get to honours level courses, as they are very often designed to meet curriculum and accreditation requirements that may be professionally or nationally specific.

MOOcs failed because they had no commitment threshold: if you were an affluent retiree you probably stayed the course, but the data showed that past the first lecture most people dropped out. I always felt MOOCs conflated and confused stage performing (lectures) with a rehearsed television series (they're just not the same thing).

As a wise man told me “Everything is possible when you don’t know what you are talking about”