Viewpoint diversity and its limits

Affirmative action for iconoclasts?

This is a free version of a post previously sent to paid subscribers, substantially revised in response to comments. I’m very grateful to the commenters and to Max Bloom, Daniel Greco, Yoel Inbar, Mickey Inzlicht, and Azim Shariff for comments on an early draft.

This is a long one, so you get a TL;DR:

Viewpoint diversity is great at the level of the intellectual community.

But it’s not necessarily something we should aspire to at the local level—in fact, when it comes to hiring faculty, viewpoint homogeneity is often better.

Fans of viewpoint diversity should recognize that trade-offs are involved—encouraging diversity involves making difficult, uncomfortable choices.

—

Just about everybody cares about, or pretends to care about, viewpoint diversity.

Many on the left pretend to care because they see appeals to viewpoint diversity as a good way to get the sort of diversity they really want, which has to do with race and gender. Many on the right pretend to care because it’s a way to have their own favored views taken seriously, land themselves plum jobs, and get their right-wing kids accepted to good universities. The Trump administration pretends to care about viewpoint diversity (they do!—see their letter to Harvard) in part for the same reasons as others on the right, and in part because it’s a clever way to own the libs, using their own diversity rhetoric against them.

The test for whether people actually care about viewpoint diversity is whether they continue to value it when it doesn’t favor their side. I’ll believe that people on the left care when they push for gender studies programs to have more emphasis on evolutionary biology. I’ll believe that people on the right care when they stop trying to get professors punished for being critical of Israel. And I’ll never believe that the Trump administration cares about viewpoint diversity because I’m not an idiot.

Viewpoint diversity is a good thing

Pretending to care about viewpoint diversity is a useful rhetorical strategy because there is a general consensus that viewpoint diversity is a good thing. It’s obvious to many that progress in the sciences and the humanities benefits from an openness to new ideas and a willingness to challenge received wisdom.

As I was writing this, I came across a Substack post that summarizes what many think of viewpoint diversity (and the lack of it in academia), featuring a nice quote from Jonathan Haidt.

I’ve long been a supporter of viewpoint diversity. I attended the most recent conference of the Heterodox Academy, which has this on its website:

We advocate for policy and culture changes that ensure our universities are truth-seeking, knowledge-generating institutions grounded in open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement - because great minds don't always think alike.

And, following Haidt and others, I’ve argued that academia has suffered from insufficient diversity—see, for instance, my Progressives should worry more about their favorite scientific findings.

We can see how acceptance of diverse viewpoints makes a difference. Looking at my own field, the areas of psychology where we’ve had the most success are those with the most vibrant debates between different perspectives. And some of our notable failures as a field—many of them revolving around the “replication crisis”—have occurred when discussion has been stifled, often because people were discouraged from challenging a politically popular orthodoxy.

As a different source of support for viewpoint diversity, a terrific article has just appeared in which the philosopher Elizabeth Barnes discusses how much she has benefited from arguing with Peter Singer about disability issues. She begins by outlining the standard arguments in support of this kind of conflict.

More often than not, when we talk about open disagreement and free exchange of ideas, we tend to focus on their broader social value. We say things like: promoting open disagreement is crucial to protecting free speech; promoting open disagreement is the only way to prevent harmful silos and echo chambers; promoting open disagreement is vital to democracy, etc.

Then she adds:

But I think an under-discussed aspect of striving to have conversations across serious disagreement is the personal value they can bring. For entirely self-interested and self-regarding reasons, I think these kinds of conversations are good for me. I think they make me a better philosopher and a better thinker.

She has a lot to say about this—really, read the whole thing—but this discussion really stood out to me:

I’ve always tried to think that the single most valuable gift that someone can give me, qua philosopher, is a really great objection. If I’m doing philosophy well, I need to care more about what’s true than about being right. And this is stupidly hard, because the longer I play with an idea the more attached to it I become, and dammit I want to be right. But if I’m messing up, I (should) really want to know. And for that, I need the best objections.

But the truth is that people who are in broad philosophical agreement with me—while they can and do provide robust criticism—are just less likely to hit me with the toughest and hardest objections. That’s not from any lack of rigor on their part, it’s just that people who are broadly sympathetic to what I’m saying are less likely to be sympathetic to opposing viewpoints, and so less likely to defend them.

… Peter is an interlocutor who has given me a tremendous gift: he will always say what he thinks. No pandering, no soft-balling, just a good old-fashioned objection. I need this more than I’d realized.

But should we value viewpoint diversity when hiring professors?

As I said, I find this all persuasive. But here I am, with some second thoughts. While I think it’s overwhelmingly positive for scholarly fields to include and welcome diverse viewpoints, I am more skeptical about the claim, often made, that we should favor viewpoint diversity when hiring new faculty members.

My arguments aren’t the usual ones. Many people are skeptical about viewpoint diversity because they worry about the harm caused by the expression of certain views. I’ve heard academics say that those who express skepticism about affirmative action can cause psychological damage to minority students. Others argue that certain anti-Israel views shouldn’t be expressed in universities because they are offensive to Israeli students or Jewish students more generally. For both communities, these types of viewpoint diversity have more costs than benefits—the juice isn’t worth the squeeze. These concerns extend naturally to faculty hiring; they are arguments for not hiring the economist who argues against diversity programs or the historian who writes about how Israel is a genocidal state.

Whatever one thinks of this anti-diversity critique—and as you can see, they are endorsed by both the right and the left—this isn’t the argument I will be making.

As a final point, we’re not discussing free speech and academic freedom here. I recently wrote a post (Why are so few professors trouble-makers) arguing that scholars with diverse views—even those that many find repugnant—should have considerable latitude to express them. I haven’t changed my mind about this. My skepticism is rather about how much we should encourage such diverse views through faculty hiring.

OK, enough throat-clearing. I have three concerns regarding viewpoint diversity in faculty hiring.

1. Some diversity gives you less diversity

Even if you favor viewpoint diversity, there’s a limit. You should be cautious about bringing into the fold individuals who themselves hold anti-diversity views.

This is a version of what has been known as the paradox of tolerance, with Karl Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies being the classic source. The paradox is that if you extend tolerance to intolerant people, you risk having intolerance win in the end. Therefore, a tolerant society may have to be intolerant of those who are intolerant.

When we think of people who are intolerant of views different from their own, it’s natural to think of those who hold extreme political or social positions, such as communists, fascists, “the woke”, the MAGA crowd, fundamentalist Christians and Muslims, and militant atheists. But there are other, less obvious threats to diversity.

Here is a story I heard from a friend (slightly modified to maintain anonymity): Many years ago, there was a prestigious psychology department where the faculty worried that they didn’t have enough people working in neuroscience, which they all agreed was a valuable area to represent. So they hired some. It turned out, though, that the neuroscientists they hired had a low opinion of research that wasn’t sufficiently similar to their own. And once the department reached a critical mass of new neuroscience hires, they worked together to make it difficult for the department to hire anyone who wasn’t a neuroscientist (and, more specifically, the type of neuroscientist they preferred). The department has become increasingly narrow in its viewpoints and will likely become even more so in the future.

2. It’s not really diversity that we usually want (or should want)

I mentioned earlier that everyone cares about viewpoint diversity, but that’s too simple. My sense is that:

People typically don’t want diversity for its own sake. Instead, they want (what they see as) good views that aren’t currently represented.

The distinction is subtle, but there really is a difference. To see this, consider that I like dessert. Now, someone might like dessert because they want a diverse meal. Something sweet adds a bit of variety after a meal of protein and starch. But that’s not why I like dessert. I like dessert because it tastes good. If you said “Paul likes a diverse dinner”, you wouldn’t be wrong, but the diversity is a by-product of me getting what I want, not a goal in and of itself.

Or consider again the neuroscience story. One could imagine that the psychologists wanted to hire neuroscientists because they read a lot of Jonathan Haidt and wanted to challenge themselves and foster a real marketplace of ideas. But (as the story was told to me), it wasn’t like that at all. They simply viewed neuroscience as a valuable approach to understanding the mind. They hired a social neuroscientist, say, for the same sort of reason that I had ice cream last night.

Similarly, one can imagine that the neuroscientists voted against hiring non-neuroscientists because that sort of work was too different from their own, and they hated viewpoint diversity. But that wasn’t it at all. The neuroscientists wanted a good department, and (they would say), you don’t get a good department by hiring people who do crap research.

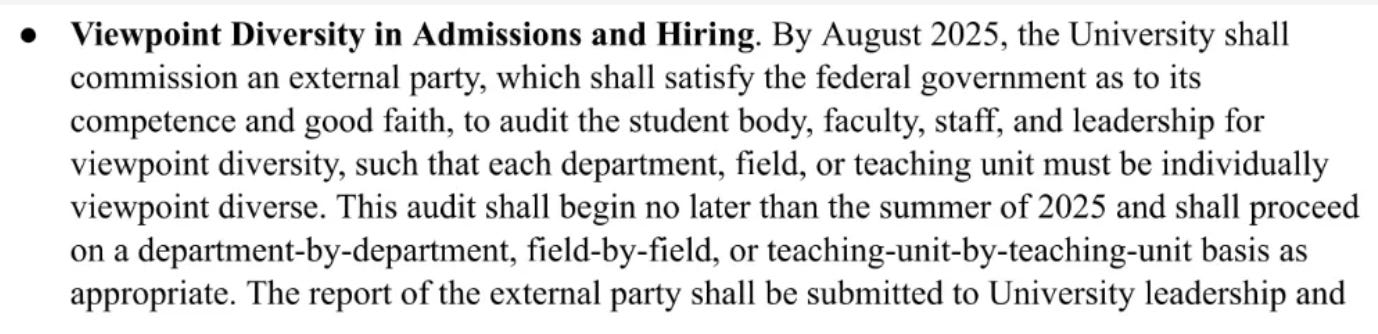

Or consider how professors respond to the demands of the Trump administration. The relevant section of their letter to Harvard begins with this:

What should we think of such a demand? A New York Times article on the topic included the following response from a strong advocate of viewpoint diversity.

Steven Pinker, a prominent Harvard psychologist who is also a president of the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard, said on Monday that it was “truly Orwellian” and self-contradictory to have the government force viewpoint diversity on the university. He said it would also lead to absurdities.

“Will this government force the economics department to hire Marxists or the psychology department to hire Jungians or, for that matter, for the medical school to hire homeopaths or Native American healers?” he said.

Plainly, some “diverse” hires are not a good idea. Marxists in the economics department, Jungians in psychology, and homeopaths and Native American healers at the med school would increase viewpoint diversity and challenge established views. But these would be ridiculous hires; no department should make them, and no department should be forced by the government to make them. (If these examples offend you because you are a fan of Marxists, Jungians, homeopaths, and healers, consider the more standard examples of Holocaust deniers in history departments and creationists in biology departments.)

Once again, this isn’t a free speech issue. If one of my colleagues decides to go full Jungian—not as hypothetical as it may sound, Jordan Peterson was once in my department—I don’t think they should lose their job or face any punishment. I just don’t think we should hire someone who works in that area.

Even if you like viewpoint diversity, then, it’s not enough for a potential hire to have views that differ from others; they have to be views worth taking seriously, as judged by experts in the area. And, yes, experts can be wrong. But there’s no alternative to making the hard choices about which views are intellectually valuable and which are not.

Here I’m following the lead of a particularly thoughtful piece by Daniel Greco, who writes

… with government grants, tenure track professorships, and the like—it’s impossible for all views to be equally supported, and anyone allocating limited resources needs to make substantive decisions about which projects are the most promising.

If you think the narrowing of academic debate is a problem, you can’t just point to the fact that some views aren’t represented; you need to make a targeted case that we’d be better off spending more of our intellectual energy discussing the views you worry we’re missing.

3. Homogeneity is good, too

A good response to this by a fan of viewpoint diversity is to concede the points above—sure, we don’t want to hire people with diverse views who themselves oppose diversity; sure, we don’t want to hire crackpots and nutcases—but to insist that, still, there is real value to viewpoint diversity within a university department. Holding everything else constant, it’s best to bring on board people who challenge the consensus.

Let’s explore this. Imagine a psychology department with a strong social psychology group that includes a community of like-minded scholars working on implicit biases. The group has the opportunity to hire a new faculty member, and there are two top candidates.

Agatha — who does research that is very much in agreement with that of the existing faculty. Agatha has appeared on conference panels with the social psychologists there; they collaborate with some of the same people, they praise and promote each other’s work on social media, and so on.

Craig — who is critical of implicit bias work and collaborates with researchers who argue that such biases are unimportant and uninteresting. When people in the department submit papers, they often request that Craig, Craig’s advisor, and their colleagues not be asked to serve as reviewers—Team Craig is described as too opposed to their work to be truly objective. (In case it matters, Craig’s own research explores explicit biases, which he believes are the only biases that matter.)1

The social psychologists will probably favor Agatha. It’s normal to prefer people who like and respect your work. And, human nature being what it is, they will probably say (and believe) that Agatha’s work is objectively better than Craig’s. But, for the sake of this example, imagine that they (begrudgingly) agree that Craig is as serious a scholar as Agatha is. Both come from reputable labs, have excellent publication records, and have received numerous awards. In fact, since I get to create this example, imagine that Agatha and Craig’s qualifications, in the eyes of someone with no skin in the game, are perfectly matched.

So, who should the department choose? For a proponent of viewpoint diversity, it’s a no-brainer. If favoring viewpoint diversity means anything at all, it means that you should prefer the more diverse candidate when it’s a coin flip situation. They should hire Craig.

I disagree. I think they should hire Agatha.

One concern is that it’s unrealistic to expect Craig to shake things up. In my experience, faculty members with different views tend to avoid conflict. (At Yale, I had a colleague who thought my research was bullshit, and yet we were great pals; we just never talked about my research.) It’s a pleasant fantasy to imagine that Craig and his new implicit bias colleagues are going to enthusiastically argue about these issues, engage in adversarial collaborations, and cheerfully work together to converge on the truth. More likely, the social psychologists will complain amongst themselves about how the rest of the department bullied them into hiring this loser and will tell their students not to take his seminars. And Craig will hide in his office and apply for jobs in departments where people might like and respect him.

(To make matters worse, there is the problem of the academic hierarchy. If Craig is untenured, he will worry about offending his senior colleagues, who will ultimately decide whether he keeps his job. If Craig is tenured, then he should worry about engaging too sharply with the junior colleagues he disagrees with, since he will ultimately decide whether they get to keep their jobs.)

Again, I’m not denying the overall value of having people of different views engage in productive debate. I’m just denying that this is what happens when people of different views are in the same academic department.

Return now to Agatha. There are real benefits to having Agatha around. She will have colleagues who are interested in and respect her work; she can collaborate with them, teach seminars with them, co-advise students with them, and all of that good stuff. Everyone benefits.

We have an expression for this in academia—something we trot out when we want to hire someone who does the same work we do: Building For Strength.

The more general point here is that, at the local level, homogeneity can be a good thing in science.2 It’s no accident that the most productive collaboration in all of psychology, between Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, was between two individuals with similar backgrounds who agreed about just about everything.

Now this can go too far. You don’t want to hire a faculty member who is a perfect clone of a prof who is already there (and I’ve seen that happen, as when a prof successfully campaigns to hire their student or their close collaborator). 100% overlap is too much. What you want is a near neighbor who is interested in the same questions as you are, respects your work, and also brings something new to the table. But 90% overlap? That’s just right.

The value of homogeneity holds more generally. Here is Peter Thiel on startups.

Startups should make their early staff as personally similar as possible. Startups have limited resources and small teams. They must work quickly and efficiently in order to survive, and that’s easier to do when everyone shares an understanding of the world. The early PayPal team worked well together because we were all the same kind of nerd. We all loved science fiction: Cryptonomicon was required reading, and we preferred the capitalist Star Wars to the communist Star Trek. Most important, we were all obsessed with creating a digital currency that would be controlled by individuals instead of governments. For the company to work, it didn’t matter what people looked like or which country they came from, but we needed every new hire to be equally obsessed.

If any readers are left at this point, someone is shouting: An academic department is not a freaking startup. OK, fine, so consider the story of the George Mason University economics department. I only learned about this through podcasts and conversations, so I asked ChatGPT to provide a summary:

In the early 2000s, George Mason University sought to strengthen its economics department by recruiting scholars who aligned with the Austrian and public choice traditions, which emphasize limited government and market-oriented policies. This strategic hiring approach was instrumental in shaping the department's distinctive identity. Notably, Nobel laureates James Buchanan and Vernon Smith were among the prominent figures who joined the faculty during this period, contributing to the department's growing reputation.

They couldn’t do what a department like Harvard could do—hire the best people across all areas. So they decided to build a tight community of like-minded people, and it paid off nicely.

Diversity is great. But have you tried building for strength?

I don’t think all departments should be like the George Mason economics department. If you have the resources, it’s good to cover a range of approaches—not so there can be productive debate, but because there is pedagogical merit in this sort of breadth. You do have to teach undergraduates and train graduate students, after all. A psychology department, for instance, should have professors who study different things—child development, social cognition, neural processes, and so on.

This consideration, by the way, is a rejoinder to those who say, “Why not just hire on merit?” Departments have never hired just on merit, and they would be foolish to do so.3 Suppose a psychology department has several people who study shyness in adolescents, but no one who studies memory. In that case, they should prioritize a new applicant who studies memory over yet another shyness maven, even if there is a shyness applicant who is, otherwise, a stronger scholar. Any decent department needs to have people who can teach about memory.

This sort of diversity—covering the right range of topics—is plainly relevant when shaping a department, and even more obviously relevant when creating a university. To put it a bit self-deprecatingly, if universities really did work by hiring the very smartest people, there’s no way that psychology would regularly be one of the largest departments.

So, yay, diversity. But we’re not talking about viewpoint diversity here. The goal with this sort of broad hiring isn’t to get to the truth through clashing perspectives and productive debate. (Nobody expects the shyness profs and the memory prof to ever talk to one another.) Instead, you want a department to be diverse because there are different jobs to be done, in the same sense that a baseball team needs good pitchers and good outfielders.

Or, as another example, a team of heroic mercenaries like The A-Team is pleasingly diverse, containing a strong but caring leader, an unstable pilot, a handsome con man, and a tough-guy mechanic who is afraid of flying. (This was made in the 80s; if it came out later, it would include a smartass computer hacker.) I think good departments work like this, except that there’s a neuroscientist, an expert on child development, a clinical psychologist, and a strong but caring department chair. But once again, this is not viewpoint diversity.

So here’s my recommendation for how to hire professors:

Try to cover the relevant areas a department needs with the best people you can get. Make no effort to bring in faculty with views that clash. It’s more trouble than it’s worth.

Two counterarguments

Suppose you agree with everything I’ve said so far. Still, there are a couple of things to worry about.

The first is best explained with an analogy. Suppose you believe that gender and ethnicity should play no role at all in faculty hiring. Still, you might end up supporting policies that favor women and racial minorities.

Is this a contradiction? Nope—sometimes there are pre-existing biases against certain groups that need to be corrected. If search committees have a bias towards men, say, one way to correct for this and get the totally merit-based system you want is to establish a countervailing bias in favor of women.

To make things unrealistically concrete, suppose search committee members assign numerical scores to candidates and hire the person with the highest overall score—but, because the committee members are sexist, they give male candidates 5 points more just because they’re men. If you do nothing, you have an unfair and sexist system, but if you respond by automatically adding 5 points to the female candidates, everything is now perfectly fair. In some cases, bias + bias = no bias.

Going back to viewpoint diversity, there might be an unfair prejudice against certain research programs, and so some countervailing bias might be called for. Greco again, this time on how some professors deal with views different from their own.

It’s not enough to note that some views are beyond the pale and gesture vaguely at crackpots and bigots. If you think we haven’t lost much by marginalizing certain kinds of dissent, then you too need to make a substantive case: that the views in question are sufficiently implausible or intellectually barren that there’s little to be learned from engaging them. As it turns out, I think that in plenty of parts of academia there’s a powerful case to be made that we need more political diversity; we’re missing out on perspectives that are not relevantly similar to holocaust denial, and our research suffers for it.

Once again, while I’m a fan of viewpoint diversity in general, I don’t think we should favor diverse views in faculty hiring—no affirmative action for iconoclasts! And indeed, maybe there should be a bit of preference for the conformists, because of the value of homogeneity.

But this consideration does make me temper my view a bit. If there is an irrational bias against people with opinions that push against the consensus—”hiring someone skeptical of our theory of implicit biases is like hiring a Nazi”—you might need some countervailing bias in favor of viewpoint diversity. Because sometimes, bias + bias = no bias.

The second concern is a potential collective action problem.4 I’ve argued that:

A department shouldn’t care about viewpoint diversity and is probably better off without it.

It’s important and valuable to have diverse views in the field.

These can be perfectly compatible. Suppose that there are psychology programs that focus on innate mechanisms and care deeply about evolutionary considerations, and others that hate innateness and are deeply suspicious of evolutionary psychology—and suppose as well that neither department will hire someone from the opposing camp. We build for strength, the departments say. We should be cool with this, so long as there are enough instances of both types of departments to sustain a vibrant debate within the field as a whole.

But it doesn’t work out so cleanly. Imagine a contentious debate in which 80% of professors support side A and 20% support side B, and suppose that this 80/20 distribution holds across all departments. If everyone followed my advice on faculty hiring, someone who supported side B would be unemployable. Side B would end up with no representation in the field because defending it would be a career-killer. And this would be a bad result for anyone like me who supports viewpoint diversity more generally.

To make this a bit less abstract, I think this situation actually holds for advocates of conservative and libertarian perspectives in certain branches of psychology and philosophy. I said that in the world I prefer, there would be no pressure for departments with a more standard progressive perspective to hire such people. No affirmative action for non-liberals; departments should act in their own intellectual interests and build communities of scholars that can work well together, and since progressives usually don’t want and don’t benefit from non-progressives in their midst, they shouldn’t be pressured to hire them. But if there are no departments that welcome such people, their ideas don’t get an airing in the field as a whole, which is definitely not the world I prefer.

So I think there is a difficult trade-off here. I still think it’s not in departments' best interests to take viewpoint diversity into account when hiring. But I’m willing to consider that they should do so anyway, taking a hit for the good of science more generally. In other words, if you really care about viewpoint diversity at the level of the field, you might have to support policies that end up hurting individual departments.

There are always trade-offs

Many years ago, I was on a search committee where we began by ranking the files separately and then doing some math to produce a ranked list of top candidates to discuss.5 We had planned ahead of time to invite the top three to four candidates, and, conveniently enough, when we looked at the spreadsheet, three candidates stood out: #1, #2, and #3 were clustered together, ranked highly by all committee members, and there was a bit of a gap before we got to #4.

Did we invite those three? No, we did not.

It turned out that they were all men. We were reluctant to bring in an all-male slate (even if we wanted to, these short-list decisions go to a higher committee, and we knew they would balk), so we short-listed a fourth female candidate, who was lower on the list.

We also threw out one of the top three candidates. He was a brilliant scholar by any measure, but as we discussed him, it became clear that the direction of his work overlapped too closely with research currently done in the department. Though we didn’t put it this way at the time, we wanted more diversity. We decided to bring in #4 instead.

Now, I know that some of you will have strong feelings about our choice to bring in a female candidate over men who outranked her in terms of research quality and productivity. This sort of thing really upsets some people—including some of the biggest fans of viewpoint diversity. But I’m telling this story here to make the point that the second choice I described involved exactly the same sort of trade-off. Our desire for viewpoint diversity meant, again, that we ended up short-listing a weaker candidate over a stronger one.

If you’re a fan of factoring in viewpoint diversity when hiring, then, you should accept that this means that merit (in the usual sense of research productivity, publications, grants, etc.) has to matter a bit less.

This raises a question for proponents of viewpoint diversity: How much should we give up to get it? That is, how far down the list should we go to find a suitably diverse candidate? And how much should departments give up in terms of cohesiveness and productivity so as to help make the field as a whole sufficiently diverse?

The issue of trade-offs isn’t limited to faculty hiring. A reader who wished to remain anonymous emailed me in response to the paid-subscriber-only version of the post and said the following about undergraduate admissions. (It’s worth noting that the reader self-identified as conservative, so he is arguing against his own interests.)

It probably is healthy for an undergraduate body to contain a representative diversity of opinions. … [But] the problem here is more difficult than conservatives like to acknowledge: most smart young people are liberal and for reasons that aren’t totally understood, universities make them more so. My own view is that meritocracy is more important than diversity of viewpoints, so it isn’t the end of the world to have top universities that vote 80 or 90 percent Democrat.

Maybe you don’t accept the premise (that smarter people tend to be liberal), and even if you do, maybe you wouldn’t make the same choice. You might value viewpoint diversity more than my correspondent and would opt for a more diverse community of students who are not as smart. Similarly, when it came to the search I described above, you might agree with the committee that viewpoint diversity is important, even if it means tossing one of our very best candidates and replacing him with someone who is less impressive as a researcher. Or you might not be willing to take that sort of hit, which means that you don’t really care that much about viewpoint diversity after all.

It’s easy to say that you value viewpoint diversity. The interesting question is: What will you give up for it?

Not sure what implicit biases and explicit biases are? For the purposes here, it doesn’t matter, but if you’re curious, see here.

For more on this, see my recent post The only interdisciplinary conversations worth having.

Thanks to Azim Shariff for convincing me of this.

Thanks to Daniel Greco for discussion of this issue.

The search was a long time ago, and we didn’t end up making a hire. To preserve the confidentiality of the process, though, I’ve changed a few key details to make it unrecognizable to any candidates or to anyone on the committee with me.

This is great. We frequently recruit to support our existing strengths vs add new areas - we're a fairly small department and we want folks who can collaborate and attract strong cohorts of students. A few searches ago, our clinical area was debating whether to hire an addiction researcher or a geropsych/lifespan researcher; clinical aging is already key area of strength for us, whereas we didn't have folks focused on addiction. I'm sure you can guess where we landed.

Hi Paul! I'd love to hear more about why you think there shouldn't be a Jungian in the Psych dept or a holistic healer pov represented in med schools. (It felt like you were saying "But these would be ridiculous hires" as if that is self-evident). To my mind this is the kind of thinking that keeps new techniques for chronic pain management from being funded or taken seriously, which is why understanding your point of view is important to me. I'm sure you have good reasons behind your thinking, but it isn't as evident to me as it might be for you...