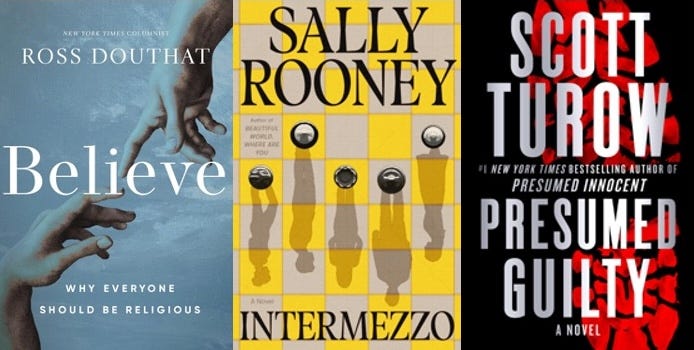

Three recommended books

(that turn out to all make the same point about sex)

It was 'Reading Week’ at my university. So I read.

Believe: Why Everyone Should be Religious by Ross Douthat

I heard Douthat make his case for religion in a couple of podcasts and found his ideas interesting—so much so that I worried when I started reading the book. Would I be convinced to abandon my lifelong atheism? Would I become Catholic? What a mess that would make of my relationships! Then again, if Douthat is right, such a decision might radically improve my afterlife, which would last much longer than my current corporeal existence.

After finishing the book, I’m still an atheist, but a bit more wobbly than when I started. I appreciated reading Douthat’s rendition of somewhat familiar ideas about fine-tuning, consciousness, and our mysterious success at understanding the world. I enjoyed, but was less persuaded by, his case for miracles and his warnings about dealing with malevolent spiritual beings. And I liked his discussion of questions I had never thought to ask, such as “If you want to become religious, which religion should you choose? This is a book that I’ll return to.

Intermezzo: A Novel by Sally Rooney

I started this book a while ago and gave up on it. It’s about two brothers in Dublin who mourn their father's death and pursue messy love affairs. The book is beautifully written and very engaging. But reading it made me feel uncomfortable. I disliked the cool and attractive Peter and worried about the awkward and intellectual Ivan. I was anxious about the fates of the women they were involved with—particularly Margaret, whose love affair with the much-younger Ivan might well ruin her life.

But I picked it up again, mostly because I couldn’t get the characters out of my head. And it got better and better. No spoilers here, but I was very satisfied with the sappy ending, and ended the book with tears in my eyes.

Presumed Guilty: A Novel, by Scott Turow.

I’m a big fan of Scott Turow and I talk about his writing here.

I read his first novel, Presumed Innocent, when I was in my twenties. I was with a group of friends in Cape Cod. A few of us got drunk one night and went swimming, and when we got back to our rented house, I was too restless to sleep and randomly picked up Turow’s book from a bookshelf. I stayed up all night reading it. Written in the first-person, it tells the story of Rusty Sabich, a young prosecutor, who is accused of murdering his lover. We find out who the murderer was at the very end of the book, and I remember how shocked I was.

In Presumed Guilty, Sabich is now retired and living in the Midwest with his girlfriend. He returns to the courtroom one last time to defend her son, who is charged with murdering the daughter of the local prosecutor. I loved it—peak courtroom drama. But either Turow is getting sloppy or I’m getting smarter, because this time, I figured out who the murderer was halfway through the first chapter.

I didn’t expect these books to share a common theme, but they did. They all discuss the importance of sex.

Douthat addresses the issue directly. In a chapter on the concerns that people have about becoming religious, he has a section called “Why Are Traditional Religions So Hung Up on Sex?” He puts the concern like this:

For the post-sexual-revolution skeptic, it’s not just that these older religious moral codes are seen as antiquated or deluded. They’re often seen as actively perverse, rooted in misogyny and patriarchy and homophobia and a fearful puritanism, inflated by the ridiculous idea that the Architect of the entire universe would care about what consenting adults do with their genitals.

His answer: You might disagree with the specific ideas that religions have about sex—about homosexuality, divorce, masturbation, etc. But of course God is obsessed with sex. He should be.

It would be a strange God indeed who cared intensely about how we spend our money or what votes we cast or how we feel about ourselves, but somehow didn’t give a damn about behaviors that might forge or shatter a marriage, create a life in good circumstances or terrible ones, form a lifelong bond or an addictive habit, bind someone to their own offspring or separate them permanently. To the extent that this God is assumed to be preparing us for a life that transcends earthly existence, it would be especially strange not to care about how people approach one of the strongest desires of the flesh, the most embodied form of passion, the kind of carnal impulse that humans are most likely to glory in and also most likely to feel as a form of bondage.

… If God cares about anything, He cares about sex; if any of your choices matter eternally, your sexual choices probably matter more than most. So in doubting the particulars of how the great religions approached sexual rules and sexuality, at least give them credit for having a more realistic view of sex than someone who shrugs and pretends that this thing that drives so much of human behavior, good and bad, somehow just isn’t a big deal.

Rooney’s book—all of her books, actually—has much to say about sexual intimacy and its consequences. As Dwight Garner put it in his NYT review

Rooney recognizes the life-changing importance of physical contact, of sex.

When Margaret and Ivan sleep together for the first time in Intermezzo, it is blissfully transformative for both of them. Garner:

She blossoms under his touch and he under hers.

Turow sees the darker side. There’s less sex in Turow’s recent book than in his earlier ones (maybe because both Turow and his main character, Rusty, are in their mid-70s). But there is a shocking act of sexual betrayal at the core of the book, one that has profound consequences for the characters we care most about.

Turow is one of the great modern writers about out-of-control sexual desire. In Presumed Innocent, the book I read so many years ago, Rusty has an affair with Carolyn Polhemus and becomes obsessed with her, stalking her when she tries to break it off., and then she’s murdered and he’s put on trial for her murder. In Innocent, it’s twenty years later and Rusty has an affair with a different woman, and is obsessed with her— then Rusty’s wife dies under suspicious circumstances and then Rusty is put on trial for his wife’s murder, charged by the same prosecutor who tried to convict him for the Polhemus killing.

Realistic? Not so much! But I’m looking forward to Turow’s next.

I wonder if Douthat explores the indoctrination aspect of religion; or perhaps the twisting of Christian ideologies to neatly fit into the purpose of destroying democracy. Anyway, that’s where I’m at with religion. Its soul purpose is to control lives. My parents had 10 kids because of they are religious rule followers. They also believed in “spare the rod spoil the child” which may or may not be religious based. A spirited child is to be broken…all that gobbledegoop that truly alters children’s lives. I may or may not read Douthat’s book, and I admit I sometimes miss the ritualistic aspect of religion during holidays, (another aspect of indoctrination) but I turned the page 18 years ago when unable to reconcile child sex abuse and subsequent church cover ups with my conscience or counseling profession. Kindness should be a religion.

When there is a religion that doesn't require faith, that will be the one. Something that is clear and coherent and makes sense to everyone who is exposed to it. Something that requires no interpretation or decoding, and that is consistent, without contradiction, and explains all existence. Something that didn't go through centuries of obvious human construction and manipulation. It would be impervious to corruption, infallible, consistent with everything else in history, and reality. And hopefully, it would be good.