This and That (7)

"A great observer of his own mistakes"

1.

My most recent discussion with Robert Wright:

When Bob (or Bob’s staff) puts together the videos of us talking together, the still picture often has me laughing at something funny that Bob had just said. This is misleading. If you watch our conversations, you’ll see that I am just as funny as Bob is.

The video above goes on for the first 45 minutes or so; we then talk for another hour in a paywalled segment. Paid subscribers to Small Potatoes get access to this second video and all other paywalled segments of my podcasts with Bob. So, ahem:

2.

In his highly recommended substackPsychiatry at the Margins, the psychiatrist Awais Aftab has a pair of posts that critically discuss the two chapters of my book Psych: The Story of the Human Mind that relate to the treatment of mental illnesses. The first is about my chapter on clinical psychology, and the second is about my chapter on Freud.

I’m grateful. Aftab’s discussion is wise and generous, and I was gratified to see that a working psychiatrist agrees with so much of what I have to say about his field. Most of our disagreements are matters of emphasis, and on some, I’m willing to concede Aftab’s points.

But interesting disagreements remain. In my Freud chapter, I had the following criticism:

One concern builds from an idea of the philosopher Karl Popper. This is the notion of falsifiability. Popper argued that one thing that distinguishes science from nonscience is that scientific theories make claims about the world that run the risk of being proven false. … The physicist Wolfgang Pauli famously derided the work of a colleague by saying, “He’s not right. He’s not even wrong,” and that’s a stinging insult because what scientists aspire to do is to generate theories that are substantive enough to be tested against the world. …

One of the main criticisms of Freudian theory is that it’s unfalsifiable. This is clearest in examples of therapeutic insights. Imagine dealing with a therapist—suppose you are treated by Sigmund Freud himself—and he says that at the root of your problems is hatred of your father. And suppose you are outraged and angrily deny it. Freud could say, “Well, your anger shows this idea is painful for you, which is evidence that I am right.” But Freud would also see support for his idea if you had said nothing or if you agreed with him. There isn’t really anything that could prove him wrong. Indeed, Freud could have said the opposite—that you have an unhealthy romantic obsession with Dad, you love him too much—and he would have taken the very same responses as support for that view.

Here is part of Aftab’s response.

I want to say something about the falsifiability part of Bloom’s discussion. What Bloom misses is that psychoanalysis takes place in a clinical context. … In the clinical context, this testing and falsifiability takes place not via formal experiments but by considerations such as how well the hypothesis explains the person’s past psychological development, what other competing explanations exist and what their merits are, to what degree the explanation resonates with the patient, and how well the hypothesis explains subsequent observations that come up in the course of psychotherapy.

To go back to Bloom’s example, why would a competent psychoanalyst assert to a patient with conviction (based on a priori or random, on-the-go speculation), “the root of your problems is hatred of your father”? A hypothesis of this sort would require evidence to support it from clinical history and clinical observation. It would likely be endorsed in the beginning with a low degree of confidence. And the psychotherapist would ideally be receptive to verification or falsification based on what the patient says in response and what is observed subsequently in psychotherapy.

Psychotherapists can certainly be dogmatic about hypotheses - and they can hold on to them even when there is very little in the patient’s statements or behaviors to support them. But scientists can be dogmatic about hypotheses in research contexts just as easily. In research, such dogmatism comes to light relatively quickly, since science progresses through open scrutiny of the evidence and attempts at replication. Psychotherapy is a deeply private endeavor. Dogmatism in the psychotherapy context is not easy to discover and scrutinize. But this is also why the discipline encourages practices by which such detection and correction can take place: an insistence on the need for rigorous training, on-going forms of peer supervision even during independent practice, avenues for presenting and discussing cases, and scholarly avenues to scrutinize and develop the theoretical foundations of the discipline.

Our disagreement summarized:

Me: When psychoanalysts have a hypothesis about a patient, there is little that can convince them that it’s mistaken. Given how psychoanalysis works, just about anything the patient says can be taken as supporting it. This reinforces their belief in the hypothesis when it comes to future patients. Ask them why they think their most recent patient has unresolved feelings towards their father, and they’ll tell you: “I’ve seen it a hundred times!” And then, once they made this conclusion, they’ve seen it 101 times!1

Aftab: Research scientists can also be close-minded and dogmatic, yet science makes progress, and bad theories are jettisoned. Why not the same for psychotherapists? Although therapy is essentially private, the discipline of psychoanalysts encourages reflection and self-criticism, and there are avenues for debate and critique. And so it makes progress too.

Plainly, the truth lies between the extremes. I’m sure Aftab would agree with me that some practicing psychoanalysts are just like my caricature of Freud. And I’d agree with him that some of them are tentative in their hypotheses and receptive to counter-evidence. Perhaps some might be willing to abandon a position like “She hates her father” upon learning more about the patient—and might go on to give up on the more general hypothesis that unconscious hatred of a parent is common among those who seek therapy.

But (not surprisingly!) I think I’m more right. Aftab says that scientists can be dogmatic, but I’d put it a different way: Scientists are people. And so they are subject to very human biases, including what’s known as the confirmation bias—we look for evidence that confirms our cherished views, not that challenges them. The writer and prominent rationalist Julia Galef calls this style of thought the soldier mindset and notes that this mindset is reflected in how we talk about our views:

It’s as if we’re soldiers, defending our beliefs against threatening evidence. . . . We talk about our beliefs as if they’re military positions, or even fortresses, built to resist attack. Beliefs can be deep-rooted, well-grounded, built on fact, and backed up by arguments. They rest on solid foundations. We might hold a firm conviction or a strong opinion, be secure in our beliefs, or have unshakeable faith in something.

Arguments are either forms of attack or forms of defense. If we’re not careful, someone might poke holes in our logic or shoot down our ideas. We might encounter a knock-down argument against something we believe. Our positions might get challenged, destroyed, undermined, or weakened. So we look for evidence to support, bolster, or buttress our position. Over time, our views become reinforced, fortified, and cemented. And we become entrenched in our beliefs, like soldiers holed up in a trench, safe from the enemy’s volleys.

And if we do change our minds? That’s surrender.

Science is rife with the soldier mindset. Working researchers fall in love with their own theories, getting high on their own supply. Nobody likes to surrender. And besides the confirmation bias, there are real benefits to being associated with a theory that your colleagues take seriously—jobs, tenure, promotions, invitations, awards, and, most of all, respect.

Theories get jettisoned, then, not because scientists seek to falsify their own ideas but because other scientists knock them down, often because they're pursuing their own pet ideas, and this other opposing theory is in their way.

This brings us back to psychoanalysis. In the passage quoted above, Aftab writes about a psychotherapist’s views about a patient, saying that a hypothesis like father hatred “would likely be endorsed in the beginning with a low degree of confidence. And the psychotherapist would ideally be receptive to verification or falsification based on what the patient says in response and what is observed subsequently in psychotherapy.”

My worry is that a lot rests on the term “ideally.” I agree that this is ideal; my concern is that it isn’t what tends to really happen. To make things worse, certain core ideas of psychoanalytic theory, such as the notion that patients can be resistant to insight, make falsification especially difficult, though not impossible.

What about falsification in psychoanalytic theory more generally, outside a particular therapeutic context? Aftab is right that there is rigorous debate in the field, and psychoanalysis has changed a lot since Freud. (And maybe I should have talked about this more in my book.)

But this debate only goes so far. The very nature of the discipline restricts the range of ideas that psychoanalytic theorists will take seriously. My sense is that few psychoanalytic theorists would be receptive to claims such as “early experiences play little role in adult mental illnesses” or “talking about one’s problems is not useful”—if they were, they wouldn’t be psychoanalytic theorists anymore! There might be a willingness in the intellectual community, then, to critique specific psychoanalytic claims—but not the whole enterprise itself.

3.

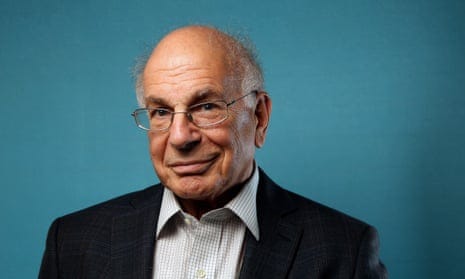

Daniel Kahneman has died at age 90. (New York Times obituary here.) If you poll a thousand psychologists and ask, “Who is the most important psychologist of our time?” Kahneman would win by a landslide. He was a brilliant scholar who produced some of the most robust and important work in our field. And he was a mensch—my Twitter feed is full of testimonials by friends, students, and collaborators about his kindness and support.

He is best known for his work in collaboration with Amos Tversky on cognitive biases in reasoning. But later in life, he made some fascinating discoveries about pleasure and happiness; I recommend his TED talk on this work:

I’ll say three things about Kahneman.

First, I talked above about how scientists fall in love with their own theories and resist being proven wrong. Kahneman was a great exception. Here is how the writer Daniel Engber puts it:

Daniel Kahneman was the world’s greatest scholar of how people get things wrong. And he was a great observer of his own mistakes. He declared his wrongness many times, on matters large and small, in public and in private. He was wrong, he said, about the work that had won the Nobel Prize. He wallowed in the state of having been mistaken; it became a topic for his lectures, a pedagogical ideal. Science has its vaunted self-corrective impulse, but even so, few working scientists—and fewer still of those who gain significant renown—will ever really cop to their mistakes. Kahneman never stopped admitting fault. He did it almost to a fault.

Second, Kahneman’s relationship with Amos Tversky (who died of cancer in 1996) is the most productive collaboration in the history of psychology. But this doesn’t mean that it was fun. In 2016, Michael Lewis wrote a book about Kahneman and Tversky called The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds. In it, he describes how difficult the collaboration was for Kahneman and how it ate away at his self-esteem.

The problem was that everyone thought Tversky was the smart one.

When others spoke of their joint work, they put Danny’s name second, if they mentioned it at all: Tversky and Kahneman. … “People saw Amos as the brilliant one and Danny as the careful one,” said Amos’s friend and Stanford colleague Persi Diaconis. … Amos’s graduate students at Stanford gave him a nickname: Famous Amos.

And Amos, who plainly loved his friend, couldn’t resist rubbing it in:

Amos may have been privately furious that the MacArthur foundation had recognized him and not Danny, but when Danny had called to congratulate him, Amos had said offhandedly, “If I hadn’t gotten it for this, I’d have gotten it for something else.” Amos might have written endless recommendations for Danny, and told people privately that Danny was the world’s greatest living psychologist, but after Danny told Amos that Harvard had asked him to join its faculty, Amos said, “It’s me they want.” He’d just blurted that out, and then probably regretted saying it — even if he wasn’t wrong to think it. Amos couldn’t help himself from wounding Danny, and Danny couldn’t help himself from feeling wounded. Barbara Tversky, Amos’s wife, occupied the office beside his at Stanford. “I would hear their phone calls,” she said. “It was worse than a divorce.”

This story sums things up:

One night in New York, while staying in an apartment with Amos, Danny had a dream. “And in this dream the doctor tells me I have six months to live,” he recalled. “And I said, ‘This is wonderful because no one would expect me to spend the last six months of my life working on this garbage.’ The next morning I told Amos.” Amos looked at Danny and said, “Other people might be impressed, but I am not. Even if you had only six months to live, I’d expect you to finish this with me.”

Third, there’s a sentence of Kahneman’s that sums up his work on the focusing illusion. It is one of the wisest things I’ve ever read. I’ve repeated it to myself many times, and it always reassures me. Maybe you’ll find it useful as well.

Nothing in life is as important as you think it is while you are thinking about it.

A version of this point comes from Karl Popper, though I forget the source.

Loving this week’s “This and That” interview with Paul bloom, and Robert Wright at the top of the Substack…. I’m a subscriber, and yet I don’t seem to be able to know how to access the behind the pay wall content of this particular interview? Just hoping for some clarification . Thank you, Malcolm.

Interesting discussion!

There's no question that all the research on confirmation bias backs up the theory that psychoanalysis and research are both going to be prone to focusing on being right, not going in lightly and being completely open to being wrong. And, the difference between research and psychoanalysis is that when a researcher is wrong, the scientific process makes that fact hard to escape, whereas psychoanalysis doesn't lend itself to that.

However, there was new research discussed in the Monitor on Psychology just this month that did discuss how discussing trauma DOES hold value. They discovered that people with PTSD experience did not work in the hippocampus at that time, whereas constructively stored sadness or neutral memories did light up the hippocampus, which organizes and contextualizes memories. They also discovered that talking about trauma helped start moving those memories into the hippocampus. Go therapy! So, that study does support the probability that psychoanalitical discussions about trauma could be productive.

Good stuff!

Doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01483-5