The worst of the deadly sins

Envy and how to defeat it

I once taught a course on The Seven Deadly Sins, and while preparing for it, I read more than one scholar who pointed out that there is only one of the sins that we are truly ashamed of.

For many theologians, Pride was the worst sin, the one that all of the others stem from. But we often feel good about feeling Pride—many of us are, well, proud of it.

It’s not Lust—maybe things were different in the 6th century when Pope Gregory thought up the list, but now people often feel good about their Lust.

Many Buddhists think we’d be better off without Anger, but there’s a case to be made that the right sort of Anger is healthy and righteous, and certainly many people feel that way.

Greed? A bit negative for some, but others would agree with Gordon Gekko from Wall Street that Greed is good: “Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind …”

Gluttony and Sloth? A bit lower on the list, but sometimes people boast about how much they ate or drank (in the original formulation, Gluttony included drunkenness), and I have heard many humblebrags about about blissful periods of laziness and irresponsibility.

There’s no competition. Envy is the worst.

People use the word in different ways, but I like this definition:

painful or resentful awareness of an advantage enjoyed by another, joined with a desire to possess the same advantage

We can feel envy about all sorts of things, including tangible items such as houses and cars and traits such as robust health, good looks, and happiness. We often envy people their relationships with other people, particularly when the relationships are sexual or romantic.

Envy hurts. Envy is associated with failure, with falling short—I can only feel envy if I lack something I want, maybe something I believe that I’m owed. To be envious is to be incomplete. And envy makes you nasty. In his book Envy, Joseph Epstein writes:

It is the one [sin] that people are least likely to want to own up to, for to do so is to admit that one is probably ungenerous, mean, small-hearted … Most of us could still sleep decently if accused of any of the other six deadly sins, but to be accused of envy would be seriously distressing, so clearly does such an accusation go directly to character. The other deadly sins, though all have the disapproval of religion, do not so thoroughly, so deeply, demean, diminish, and disqualify a person.

A couple of weeks ago, I saw a movie called Fair Play. Emily and Luke work at the same cut-throat hedge fund firm and they get secretly engaged. Then Emily gets the promotion that Luke wants, and Luke is consumed with envy. As Luke’s envy grows, both Emily and his co-workers begin to view him with disgust—the word “pathetic” is used. He becomes sexually insecure; his envy transmuting into irrational jealousy. His behavior becomes increasingly erratic, and the movie does not end happily.

No, I’ve never heard anyone boast about their envy.

Not all social comparison involves envy. There’s a good friend of mine who has a nicer house, and I wish mine was like his. But I don’t feel envy in the sense that I’m interested in exploring here, because there’s no pain or resentment associated with my desire. I’m happy for him. It’s just: “Man, that’s a great kitchen! I’m going to try to build one as good as that.”

But when I was a teenager, a close friend had a girlfriend before I did, and I can still feel how much it hurt, and how I felt a sort of hatred toward him.

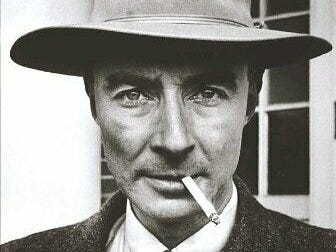

It makes me feel better to know that more accomplished men than me have felt that sort of envy. As a young man, Robert Oppenheimer was an Incel long before anyone thought of the word.

Oppenheimer was once brought to an almost homicidal rage while watching a couple “making love” (his description) in an adjoining train compartment. When the man leaves, Oppenheimer approaches the woman and kisses her, then falls at her feet, sobbing, begging her forgiveness. When they get out at Southhampton station, Oppenheimer’s rage returns; he sees her on a platform below him and tries to drop his suitcase on her head. (Fortunately, he misses).

And there’s this story, from the biography, American Prometheus. Oppenheimer was 21 at the time. Fergusson is his best friend.

Fergusson showed him some poetry written by his girlfriend, Frances Keeley, and then announced that he had proposed to Keeley and she had accepted. Robert was stunned at this news, and he snapped. “I leaned over to pick up a book,” Fergusson recalled, “and he jumped on me from behind with a trunk strap and wound it around my neck. I was quite scared for a little while. We must have made some noise. And then I managed to pull aside and he fell on the ground weeping.”

Envy isn’t limited to the young. When I was an assistant professor, I had lunch with one of the most senior figures in my field, someone I greatly respect. We were discussing travel plans and I mentioned that I was leaving in a few days to present my work at a conference. His face reddened a bit and he glared at me in sudden anger and asked:

“Why the hell didn’t they invite me instead?”

One potential salve for envy is that there are many ways to do better than others. The world would be a rougher place if there was just a single status hierarchy—based on how much money one made, say—but we are lucky enough to live in a society with multiple ways to excel. Will Wilkinson put it like this:

The cultural fragmentation some critics lament is precisely what liberates us from unavoidable zero-sum positional conflict. Surfer dudes don’t compete with Star Trek geeks for status.

In an article published in the Boston Review on status and luxury goods, I elaborated on this point, writing:

My neighbor has a Rolex and a Ferrari, so he is richer, but my children are better looking and better behaved. He is more fit, but I’ve published in Boston Review.

The idea here is that there is something that my neighbor has that I covet, but to feel better, I can remind myself that there are things that I have that my neighbor might covet, or at least that I can feel superior about. So I feel better about myself, and my resentment fades.

I used to believe this was the solution to envy, but now I’m more skeptical.

First, it would be nice if everything worked out evenly in the end, but it really doesn’t. What do I do if my neighbor is richer, fitter, and publishes in better outlets? Sure, there’s always some domain where I have an edge—maybe I know more about Star Trek than he does—but it’s not like everything counts equally. My detailed knowledge of the history of the Vulcan-Romulan conflict isn’t exactly on par with his tasteful and spacious modern house. He doesn’t covet my geek cred like I covet his house, and nobody looks at the two of us and thinks we’re even.

Face it: There are a lot of people in the world, and some of them will be better than you in every conceivable way. Worse, some might live across the street or have their office down the hall.

Also, it’s not clear how this process of compensation is supposed to work. Envy is specific. Oppenheimer was deeply resentful of other men’s romantic and sexual successes. It might cheer him up to think about how smart he is—smarter than the guy on the train, smarter than Fergusson, smarter than everyone he knew. But how does this make his particular resentment disappear?

Finally, even if it worked, there’s something sordid about the whole thing. When someone is more successful than me in some domain, do I really want to contemplate how they are less successful than me in another? Is it healthy for me to try to focus on my neighbor’s teenage son with a drug problem, thinking ha ha my kid is better? Do I need to bring him down to bring me up? In her book on the deadly sins, Dorothy Sayers describes envy as “‘the great leveler”—”if it cannot level things up, it will level them down … rather than have anyone happier than oneself, it will see us all miserable together.”

In this spirit, there is an old joke from the Soviet Union, recounted by Steven Pinker in Enlightenment Now.

Igor and Boris are dirt-poor peasants, barely scratching enough crops from their small plots of land to feed their families. The only difference between them is that Boris owns a scrawny goat. One day a fairy appears to Igor and grants him a wish. Igor says, “I wish that Boris’s goat should die.”

There’s something unpleasantly Igor-like about scrambling for advantage as a cure for envy.

I think I have a better solution, but to frame this, it will help to make a few more observations about envy.

Who do we envy? Most of my examples so far have had to do with friends, partners, colleagues, and neighbors, and this is no accident. As people move away from us, in space, time, and status, envy fades. My neighbor’s greater wealth might stir my envy. But I’m not envious of Bill Gates's wealth, even though he is much richer than either of us. Many people hate billionaires, but I think the only people who envy them (in the strong resentful sense of envy) are other billionaires.

From Silence of The Lambs:

Hannibal Lecter: He covets. That is his nature. And how do we begin to covet, Clarice? Do we seek out things to covet? Make an effort to answer now.

Clarice Starling: No. We just...

Hannibal Lecter: No. We begin by coveting what we see every day. Don't you feel eyes moving over your body, Clarice? And don't your eyes seek out the things you want?

Lecter is talking about desire, but the same point applies to envy. We envy what we see every day. Sadly, this means we envy those we are closest to, particularly if we want the same things. Luke’s envy of Emily’s promotion was made worse by their intimacy, not better.

It’s the same with friends. Here’s Adam Smith, in his Theory of Moral Sentiments, written in 1759, talking about someone who has good fortune

he may be assured that the congratulations of his best friends are not all of them perfectly sincere. … envy commonly prevents [them] from heartily sympathizing with his joy.

There are exceptions to this rule of closeness, though. As a rule, parents don’t envy their children. When good things come to my sons—even things that I would have wanted when I was their age, even things that I might want right now—I’m genuinely happy. Zero envy. I don’t envy my graduate students and postdocs either, even when they achieve successes and awards that I’ve never gotten.

Part of what’s going on here is that I see their successes as my successes. Psychologists have an expression for this (of course we do); we call it Basking in reflected glory (BIRGing).

BIRG-ing happens with other relationships as well. A while ago, when I lived in New Haven, a man a few houses down the street from me won the Nobel Prize. This wouldn’t inspire envy in the first place (it wasn’t something I was hoping for), but my feeling was more than neutral—I felt pleased. My street! I once helped him shovel out his car! When Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize many years earlier, again, many psychologists, including me, were thrilled. One of us! We know the guy! We sort of won the Prize too!

Now, it would be nice if we could BIRG at will, if we could mentally throw a switch from

that bastard I hate him so much he got what I want

to

so happy for him his success is my success too

But, of course, it doesn’t work that way. You can’t change how you feel just by wanting to. (While we’re at it, lust, greed, anger, and so on also can’t be switched on and off by sheer force of will.)

So here’s my advice. I don’t think it’s a cure-all, but it helps. To lay it out, take one of Epstein’s examples:

If you wish to smell envy in the very air, visit Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Chicago, Berkeley, or Stanford the morning after the MacArthur Genius (so-called) grants are announced.

So it’s morning, the grants have been announced, and you’re not on the list, which is fine; you hadn’t expected it. But then you see that your colleague down the hall won, the colleague who does work very similar to yours, and you feel an Oppenheimer-like rush of rage. How come there’s never a trunk strap around when you need one?

Don’t. Don’t murder them. Certainly, don’t bitch about them to your friends. Do this instead:

Congratulate the person. Warmly and fulsomely. Share the good news with others.

There are two reasons this works:

1. Impression management

A while ago, I had a conversation with Alex Shaw that got me thinking about the third-party nature of envy. He pointed out that when we envy another’s accomplishments, part of the pain is the worry that others think less of us. The envious feeling when a friend wins a great prize isn’t just

that bastard I hate him so much he gets everything and I get nothing

it’s also

everyone thinks I’m a loser

It’s not just that Luke is hurt because Emily got the job Luke wanted; it’s also that everyone (including Emily) knows that Emily got the job that Luke wanted, and so he feels diminished in the eyes of others.

This might be part of the reason we tend to envy those close to us—we believe (with some justification) that we are liable to be compared with them. My friends who visit me may notice that my neighbor has a nicer house and judge me for that; they aren’t likely to think less of me because Bill Gates has a nicer house.

This may also explain, as Alex proposed, why we are most envious of those accomplishments and traits that others most value, such as money, fame, and prizes. These are the basis of their comparisons. I can envy my neighbor’s higher ranking at Pokémon Go, but this doesn’t burn like my envy for his house because nobody else in my community cares that much about Pokémon Go. There is no third-party ingredient to my suffering.

When you tell the winner—and tell the world—how happy you are, they will think better of you. This sort of congratulations comes from a position of strength, after all. People will infer that you are not resentful, which means that maybe you don’t want the Genius Award; maybe you feel like you’ll get it the next time; maybe your ambitions lie elsewhere. There may be a loss of relative status, and it might hurt, but nobody will see you as pathetic.

2. Act as if ye have faith and faith should be given to you

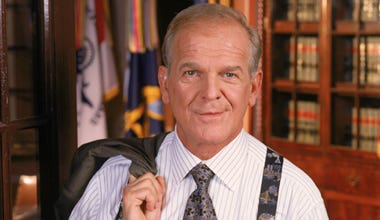

When I first saw this quote, I assumed it was from the Bible, but it actually comes from Leo McGarry, the character from The West Wing, which probably means Aaron Sorkin wrote it.

I like Aaron Sorkin and think it’s good advice. If you act as if you think something is true, it becomes more likely to be true. (“Fake it until you make it,” is the cruder version.) If you are mildly depressed (and this is all I’m talking about here—a bit of unwelcome sadness), it’s smart to try, as best you can, to do non-depressed things. Take a shower, put on clean clothes, go for a walk in the sun, smile.

It's the same with envy. Act as if you’re not envious, and with luck, your spirit will come into synch with your actions.

It doesn’t always work. It’s more complicated when the person you envy isn’t someone you like, or, worse if it’s someone who doesn’t respect you or even who gloats about how they’ve beaten you. It’s more complicated when you’re envious of an ongoing situation, like when you are lonely and living with a roommate who is deeply in love. But even if it fails, and your envy continues to burn, you’re acting like a better person, and people will think of you as such. Not bad for failed advice.

One last thing: Don’t think of this as some Jedi mind trick, some clever technique to fool others and ultimately fool yourself. That’s not it. Right now, you feel envy, and you don’t want to. It’s ugly and shameful. But you also feel other things; you retain some capacity for real joy in the happiness of others, particularly when you are close to them. Oppenheimer loved Fergusson; Luke loved Emily. The advice isn’t deception or pretense; it is taking the good inclinations you possess—the ones you are proud of, those that reflect the person you want to be—and expressing them in your behavior, transforming resentment into love.

Worth it just for the impersonation.

Also big positive/zero sum energy, if Mr Wright is struggling for a topic next time you chat.

Jon Haidt's version is common humanity which captures that much political gnashing of teeth is actually garden variety... envy.

Also: top Substack joke-teller 💪

Thought-provoking as usual Professor.

First, I’d like to offer the idea (not mine*, so please don’t anyone envy me if you wish you’d thought of it) that greed is the mother of all sin, which I interpret as excessive (harmful) desire for anything. Thus greed = excessive desire = sin. Sloth is greed for comfort; gluttony is greed for food and drink; lust is greed for sex. Pride and anger, as you mention, are only sinful in excess - this is a language problem. For example, excess is built into the meaning of gluttony. Excessive pride is greed to feel superior (excessive self-worth); excessive anger is the feeling of being wronged plus excessive pride; and envy is anger plus greed for what another has (coveting). So, in a sense, your thesis that envy is the worst is understandable, as it contains anger, which contains pride, plus coveting!

Second, I would have added three other whoppers to the list of 7: authoritarianism - greed to control others; cowardice - greed for safety; and attention-seeking - greed for attention. ‘Nuff said these days, I reckon.

Third, and finally, my recommendation to overcome envy: learn to be happy with who you are, not what you do or have. Then your only worry is sloth!

* From one of Idries Shah’s books; sorry, I don’t remember which one. My explication of the idea is my own, though.