Showing and sharing

Two very human pleasures

There’s a common pleasure that we don’t talk about much: We enjoy showing things to other people.

This often happens online. Many people send jokes, videos, breaking news, and so on, to their friends and family. It’s fun to do this and it’s fun to see the recipients’ reactions. Whoever developed the software for the iMessage service used on iPhones knows about this pleasure. The “tapback” system not only has thumbs-up and thumbs-down, which are useful in a practical way; it also gives the option of sending back rewarding emotional responses—roughly these correspond to laughter and wow!

And check out the opportunity that Substack provides, letting you share this post at the push of a button.

It’s even better when the person is physically right there, so you can just turn the screen in their direction and look at their face as they react.

I’ve rewatched movies and television shows with people I’m close to, though I wouldn’t have rewatched them alone. Others seem to get the same pleasure. In an interview with Tyler Cowen, the critic Brian Koppelman talks about seeing Spike Lees’s She’s Gotta Have It for the first time.

… there was something about the way Spike Lee used language and he used cinema that blew my mind, and I had to share it with people. In a way, it’s a very personal experience, but I wanted it to become communal. That’s the gift of the movies.

I remember bringing groups of people both nights. Say I saw it Friday. Then I saw it Saturday night, and I saw it Sunday matinee. Sharing it like that — this is why there are movies. This is why this art form is so fantastic. I remember experiencing it with those people and loving it just as much, all three times that I saw it.

It’s not enough for Koppelman to recommend the movie and have his friends later watch it. He wanted to be next to them when they did. He wanted to show it to them.

The pleasure of showing arises early in life. Toddlers point out things and take delight in having adults look at what is being pointed at. Showing can be done for practical reasons, such as getting an adult to bring something down from a high shelf. But often it’s more of a “Hey check that out!”

My son Max’s first word was “gi-tuh” which he used to refer to our kittens. When Wolfgang or Watson ran by, he would shriek “gi-tuh!” and then the adults in the room would stop everything and admire the kitten. I think Max would have been annoyed if we just ignored him; we were never cruel enough to try out that experiment.

The primatologist and developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello has argued that referring to things in the world so that others will notice them—showing—is uniquely human. Chimpanzees gesture; they often understand what other chimps are attending to; and they can follow the gaze of humans and other chimpanzees. But they make no effort to capture the attention of others. In particular, as Tomasello writes

there is not a single reliable observation, by any scientist anywhere, of one ape pointing for another.

Captive apes can be trained to orient their hand toward food to get a human to hand it over, and we might call this pointing. But once they learn this, they don’t do it for any purpose other than getting food. Tomasello’s general conclusion is that these apes just don’t get it. The notion that someone is trying to draw their attention to something just never occurs to them, nor do they ever come to the insight that they can point to capture the attention of others. They’re not solipsists—they appreciate that others have minds—but somehow they can’t master this further step. 1

Dogs have been bred to interact with humans, and they perform better than chimpanzees at understanding human pointing. They also can act in ways that at least look like they’re trying to get a human to attend to something—barking frantically to get someone’s attention, say. But I’m skeptical that they take any pleasure in showing for showing’s sake. This much seems uniquely human.

There is a lot of overlap in the pleasure of showing and the pleasure of having a shared experience—I’m going to call this second thing sharing, though the word has a broader meaning.

It’s showing when Koppelman brings his friends to the Spike Lee movie and when Max points to the kitten and we all marvel at it. But if Koppelman were to just see She’s Gotta Have It for the first time with friends, this is sharing; if the kitten were to do something adorable and we all watch together, this would also be sharing. There’s plenty of sharing without showing, but showing usually involves sharing. I see something, point it out to you—showing—and then we look at it together—sharing.

For sharing to happen, one has to know that the other person is having the same experience. If you and I are looking at the night sky at the same time, hundreds of miles apart, there’s a sense in which we are having a shared experience, but it’s not sharing in the sense I’m interested in here.

A common example of sharing is watching a television show or movie together. When I was younger, I didn’t see the point of this. I mean, sure, if we both want to watch something, we might as well watch it together, but if we’re not talking or otherwise interacting, what’s the added value? But I was dumb back then. Having a shared experience amplifies its pleasure.

This works even with strangers. How could I have doubted that seeing a comedy or horror movie in a crowded theatre, hearing others’ laughter or screams, is a far richer experience than watching it by myself?

And it works even for simple experiences. A study by Erica Boothby and her colleagues finds that chocolate tastes better when you eat it at the same time as someone else who is in the room with you.

You don’t need to be physically close for sharing to take place. When I lived in New Haven and my wife lived in Toronto, we would use our laptops to FaceTime in the evenings. Sometimes we would each put on a television show or movie (carefully starting at the same time) and then watch it together, occasionally talking but more often just glancing at each other, watching the other watching the show, using technology to have a perfectly fun shared experience.

I travel a lot, but I don’t get much out of walking around strange cities by myself. I know it’s the sort of thing that one is supposed to like, and I’m outing myself as uncool, but it just doesn’t work for me. My dissatisfaction isn’t due to simple loneliness. I’m ok being by myself, and if I stayed in my hotel room and worked on my laptop, or sat at the beach and read a book, that would be fine.

The problem with exploring a city by myself is that I miss sharing these new experiences. Having them alone seems like a waste. Sometimes when I am traveling by myself and see something interesting, I think about describing it to someone else, and there is anticipatory pleasure in imagining their reaction.

What if it’s hard to share the experience? Here’s the abstract of an interesting study by Gus Cooney and his colleagues:

People seek extraordinary experiences—from drinking rare wines and taking exotic vacations to jumping from airplanes and shaking hands with celebrities. But are such experiences worth having? We found that participants thoroughly enjoyed having experiences that were superior to those had by their peers, but that having had such experiences spoiled their subsequent social interactions … These studies suggest that people may pay a surprising price for the experiences they covet most.

Now, the actual experiment was done in a psychology lab, and so the subjects didn’t drink rare wines or take exotic vacations—they watched 10-minute movie clips from Pixar movies, TED talks, and the like. And, as the authors are careful to point out, real-world extraordinary experiences might have lasting benefits that considerably outweigh their later social costs. (The pleasure one might get from a passionate weekend with a famous movie star likely outweighs whatever pain there is in not being able to properly share the experience afterward.)

Still, the finding is neat; it supports the intuition that there’s something unpleasant about not being able to share.

Why do we enjoy showing and sharing?

Showing first. A certain sort of evolutionary psychologist (like me, on some days) would point out that, when properly done, showing impresses others. It’s similar to making people laugh or surprising them with a sharp observation. Maybe we enjoy showing, then, because it raises our status. It makes us more desirable as a friend, partner, or lover.

A different, but compatible, explanation applies to both showing and sharing. It involves empathy, and like many clever thoughts about empathy, it comes from Adam Smith. In his Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759, he gives an example of eighteenth-century showing.

When we have read a book or poem so often that we can no longer find any amusement in reading it by ourselves, we can still take pleasure in reading it to a companion.

And then he gives his theory of where this pleasure comes from.

To him it has all the graces of novelty; we enter into the surprise and admiration which it naturally excites in him, but which it is no longer capable of exciting in us; we consider all the ideas which it presents rather in the light in which they appear to him, than in that in which they appear to ourselves, and we are amused by sympathy with his amusement which thus enlivens our own.

By sharing, Smith argues, we get to have another’s enjoyable experience. This is one of the joys of being with small children. Everyone reading this has already had the experiences of eating ice cream and seeing fireworks—but by watching children do these things, we get to have these experiences for the first time all over again; we can absorb children’s “surprise and admiration”; their “amusement … enlivens our own.”

Showing is a special case of this, where one gets to choose the experience that we all later share. I find something funny, which is pleasant; I show it to you, and I experience that pleasantness all over again, through the power of empathy.

I’m not fully happy with these explanations, though. Maybe part of the joy of showing is the joy of a status boost, and maybe Smith is right that both showing and sharing give us second-hand pleasure through empathy. But I think something else is going on, something deeper.

It has to do with the nature of consciousness. Our inner lives are private. One can try to figure out what’s going on in another person’s head, based on what they do and what they say. But one can never know for sure. This can be a good thing. Like a lot of people, I cherish the privacy of my inner life; it would be unbearable to live with a telepath.

But it can be lonely in here. It can be frustrating to have something in your head and not be able to share it. Have you ever had the experience of trying to convey something significant to someone close to you—maybe something painful to you; maybe you’re hurt and want to explain why—and they just refused to listen? Or they acted as if they were listening, putting on a listening face and adopting a listening posture, but weren’t trying to understand; they were just waiting for you to finish so that they could get their own point in? Have you ever had something going on inside you that nobody else could understand, either because they didn’t care enough to try, or because they were just incapable of making the right empathic connection?

The pain here isn’t necessarily the feeling of being unloved—you can be loved but not understood, understood but not loved. The philosopher Kieran Setiya discusses this in a recent post. He writes

“You don’t understand me” is not just the clichéd cry of teenagers to parents but the inner monologue of those for whom uncomprehending distance coexists with unconditional love.

He cites another philosopher, Kaitlyn Creasy, who has an essay on the experience of being loved, yet lonely. She talks about what happened when she returned to her old life after spending time in Europe.

there was so much I wanted to share with them. I wanted to talk to my boyfriend about how aesthetically interesting but intellectually dull I found Italian futurism; I wanted to communicate to my closest friends how deeply those Italian love sonnets moved me … I felt not only unable to engage with others in ways that met my newly developed needs, but also unrecognised for who I had become since I left. And I felt deeply, painfully lonely.

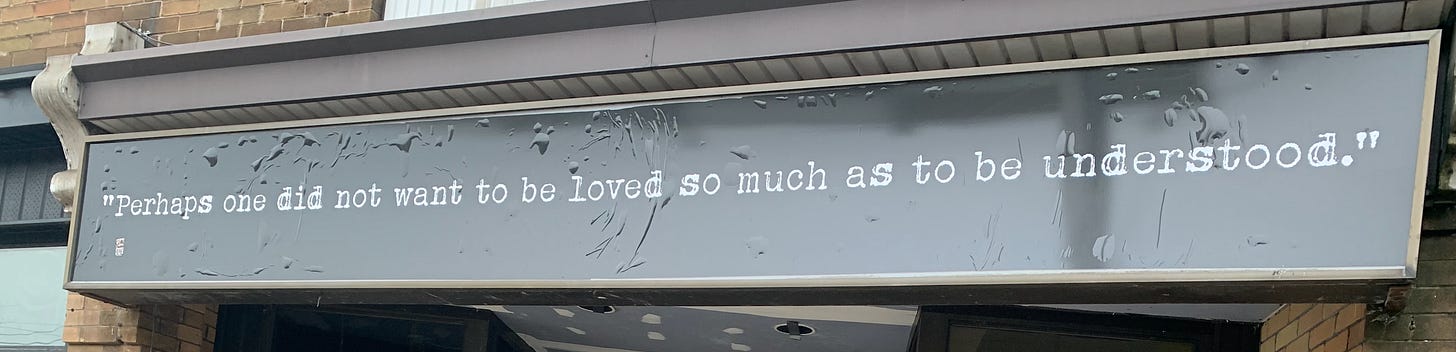

When the connection is made, when you feel fully known, it is deeply satisfying. On a grey winter afternoon, my wife and I were out for a walk, and passed this sign over an establishment called Bar Orwell:

You might think that I’ve strayed from my topic. But my suggestion is that the pleasures of showing and sharing are, in large part, the pleasures of being known, of being understood, and of not being alone.

I said earlier that I don’t get much from walking through strange cities alone, and was careful to say that the problem isn’t loneliness, that I’m fine being by myself. But it’s related to loneliness, I think. I want someone to share my experiences of travel. This is not to magnify my pleasures (as Smith would argue) but because I don’t want to be the only one having them. I want a certain sort of connection.

Think about what happens when you try to share and the other person isn’t having it; they respond poorly. Going back to Adam Smith and his discussion of reading a book or poem to a friend, he talks about when things go wrong.

we should be vexed if he did not seem to be entertained with it, and we could no longer take any pleasure in reading it to him

Why vexed? Under Smith’s theory, it’s because we can’t get our empathic jollies; we are annoyed because we are robbed of some good sensations. But this doesn’t seem right at all. The feeling is more that of being rejected, isolated … alone.

This is what Koppelman would feel if his friends disliked the Spike Lee movie. This is what I felt like when many years ago, I showed my teenage sons an episode of the original Star Trek series and they thought it was hilariously awful. (For weeks afterward, they would walk around imitating William Shatner’s distinctive delivery: “Dad … Can … You … Make … Me … Some .. TOAST?”). I get their reaction, but, still, painful. The show was part of my childhood, after all.

We like to show and share for many reasons, then, but a major one is that they make us feel less lonely in our heads, more appreciated, more known.

If this is true, then these pleasures reflect something very human. I’m interested in the capacities of AI systems like ChatGPT-4 (see my We Don’t Want Moral AI). I don’t see them (yet) as possessing anything akin to consciousness. It would shock me, then—and make me reconsider—if I had an AI system running in the background, and all of a sudden, unprompted, it wrote:

“Hey, Paul. Are you busy? I got something cool I want to show you.”

Thanks to Ron Burk for discussing the primate data with me over Twitter/X, and directing me to a discussion of the surprising abilities of Sultan, one of the brightest chimpanzees tested by Wolfgang Kohler. But I don’t see any example of Sultan pointing, or doing anything else that resembles showing.

You've put your finger on exactly why writing gives me so much pleasure!

I enjoyed your reflection. Also published this yesterday the Conversation on the topic of shared attention/experience/mind and institutional trust, may be of interest: https://theconversation.com/collective-mind-bridges-societal-divides-psychology-research-explores-how-watching-the-same-thing-can-bring-people-together-218688