Is clinical psychology stagnant?

Therapy works …

I often get emails from people who take my online Introduction to Psychology course. While they sometimes ask me about theoretical approaches or research findings, they are most often reaching out because they are suffering from psychological problems, such as depression, obsessive thoughts, or panic attacks. They are miserable and desperate, and so they contact the only psychologist they know. Some of these emails are heartbreaking.

I’m not the right person for this. The first thing I say when I reply is that I’m a research psychologist, not a therapist. (As a friend of mine puts it, “I’m a psychologist but not the sort that helps people.”) But I do give advice. I say that they should seek help from an expert. They should get therapy.

I recommend this because the evidence suggests that, on average, therapy is better than no therapy.

It’s not just that people report feeling better after they talk to a therapist or take the right drugs. This doesn’t show much—maybe they would have gotten better anyway. To test the efficacy of therapy, one needs a control group that includes the same sort of people as the treatment group so that it’s pure luck who gets therapy and who doesn’t. For instance, you might start with six hundred people who are looking to get some sort of therapy—three hundred of them will get treatment, and three hundred will be put on a waiting list. And when you do this, study after study finds those who get the therapy tend to do better than those who don’t.

Therapists know some surprising things about mental illness. One psychiatrist, Randolph Nesse, writes:

Recognizing common patterns can make even ordinary clinicians seem like mind readers. Asking a patient who reports lacking hope, energy, and interest, “Does your food taste like cardboard, and do you awaken at four a.m.?” is likely to elicit “Yes, both! How did you know?” Patients who report excessive hand washing are astounded when you guess correctly, “Do you ever drive around the block to see if you might have hit someone?” If a student has weight loss and a fear of obesity, she will likely be astonished when asked, “You get all A’s, right?” Clinicians recognize these clusters of symptoms as syndromes: major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and anorexia nervosa. After seeing thousands of patients, expert clinicians recognize different syndromes as readily as botanists recog- nize different species of plants.

Therapists also often know how to make people better. There are good ways to treat certain anxiety disorders, for instance. Nesse again:

Patients with panic disorder get better so reliably that treating them would be boring if it were not for the satisfaction of watching them return to living full lives.

Some therapies are plainly better than others for specific disorders, but what’s surprising is that there seems to be a general benefit to therapy regardless of type. In 1936, this was playfully dubbed the Dodo Bird Verdict. This is a reference to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where the Dodo Bird ran a competition in which the characters who had gotten wet had to run around the lake until they were dry. When the Dodo Bird was asked who had won, he thought and said, “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.”

The idea here is that there is something that all (or just about all) therapies do right. Perhaps it’s the bond that the client has with the therapist—sometimes called the “therapeutic alliance.” There is support; you’re dealing with a person who accepts you, who feels compassion for you, who encourages you, who guides you, who is on your side. And then there’s hope. When you go into therapy, it is usually with some faith that this will work. You wouldn’t be there if you didn’t think it had some chance of success. This sort of hope could be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Believing something will work is often an excellent first step to making it work.

… But it’s not where it should be

I cannot stress this enough—if you are in distress, seek treatment. It works. But, and I can’t stress this enough either, the treatment of mental illness is at a primitive stage. We have a long way to go.

Things once looked rosy. In the late 1800s, one of the major mental illnesses, “general paralysis of the insane,” was found to be caused by a syphilis infection and could be treated just as one treats syphilis. The hope at the time was that other mental disorders would come to be diagnosed and cured in a similar way. (See here for a good discussion.)

Sadly, though, general paralysis of the insane was a one-off—this sort of victory never happened again.

There was a similar wave of enthusiasm in the last decade. In 2013, Thomas Insel, the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, announced that the institute would move away from traditional clinical categories and pursue a more scientific taxonomy, one grounded in neuroscience and genetics. He believed that this would lead to a revolution in treatment, and many scientists and clinicians shared his enthusiasm.

And how did it work out? Here is Insel’s summary years later.

I spent 13 years at NIMH really pushing on the neuroscience and genetics of mental disorders, and when I look back on that I realize that while I think I succeeded at getting lots of really cool papers published by cool scientists at fairly large costs—I think $20 billion—I don’t think we moved the needle in reducing suicide, reducing hospitalizations, improving recovery for the tens of millions of people who have mental illness.

Insel’s predecessor at NIMH, Steven Hyman, recently chimed in with a similar sentiment:

No new drug targets or therapeutic mechanisms of real significance have been developed for more than four decades.

More than four decades! There is a lot we understand about the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness—Nesse is right in the quotes above—but it’s fair to say that progress here has been slower than hoped.

You would know this if you have ever sought treatment. Talk therapy—where you meet with a therapist and discuss your problems—often works, but not always, and usually not quickly. And nobody quite knows why it works. It’s frustrating that the specific person you are talking to might make more of a difference than any techniques that they are using.1 If there is a secret sauce, we don’t know what it is.

Then there are drugs. Again, these do help, but it’s not like taking antibiotics for an infection. Psychiatrists often go through a lengthy period of trial and error to find the right drug for a given patient. Sometimes, a drug will work for a while and then stop, and the process has to start again. Since it takes a long time to see whether something is effective, this can be a miserable slog. Side effects occur—some of them serious, involving weight gain, insomnia, and sexual problems—and so many people who would be helped by medications give up on them.

(Why haven’t drugs improved? One answer is that creating new drugs is expensive and time-consuming—they take a long time to test, and there are considerable regulatory hurdles. Apparently, many drug companies have lost interest.)

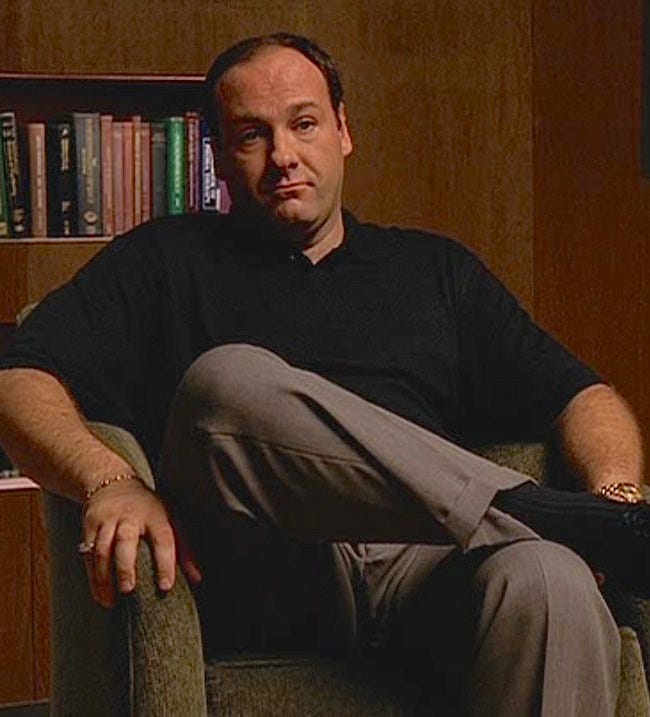

My sense here—and it’s one that I share with some clinical psychologists I’ve spoken to, though I would love to hear from others, as well from psychiatrists—is that the field has largely been stagnant when it comes to the treatment of psychological problems revolving around anxiety and depression. There’s just no big difference in what it would be like to be treated now versus being treated in, say, 1999, when the first season of The Sopranos appeared on HBO, and Tony Soprano first met with his therapist, Dr. Jennifer Melfi. If you want a sense of what the therapy was like, here is my favorite scene (I show it to my Intro Psych students when introducing them to clinical psychology):

Now, this isn’t to say that nothing has changed. There are therapists who are trying out alternative treatments outside of the scope of traditional talk therapy and traditional psychopharmacology, and I’ll get to these below. Another positive development has been an expansion in the availability of therapy. Largely sparked by the pandemic, a lot of treatment has moved online, giving access to those who, for various reasons, can’t work with the traditional 50-minutes-in-a-private-room mode of treatment.

There have also been advances in treatments for certain specific problems, most notably psychosis, a disorder where there is a sharp break from reality. Commenting on an earlier draft of this post, a clinical psychologist friend of mine wrote,

A ton of research demonstrated that early intervention really matters for psychosis, and now there are many first-episode psychosis clinics across the country … They involve team-based care, offering everything in one spot (therapy, meds, vocational and educational counseling, support and education for the family, general social work and case management, social skills training, and various other possibilities). … A patient with early psychosis, if they live in a city that has [such a] clinic, is likely to receive very different (and more effective) care now than they would have in 1999.

So, a conclusion of total stagnation would be wrong, and the answer to the question that titles this post should be “No, clinical psychology has made some progress.”

But, still, if a therapist were to watch The Sopranos for the first time, there isn’t much to tell them that it wasn’t filmed a month ago. And if you were to go to a therapist now for the usual reasons—sadness, distress, anxiety—your experience wouldn’t be much different from Tony’s. You probably won’t be given Prozac, but if you get a prescription, it’s likely to be not so different from Prozac in its chemical composition. And the way your therapist would talk to you and the guidance that he or she provides will be pretty much the same as what Tony got from Dr. Melfi 25 years ago.

Now, if therapy quickly and reliably cured people’s problems, this stasis would make sense—why mess with success? But it doesn’t.

Could things change?

Sure. Perhaps a revolution is right around the corner. Maybe it will come from advances in Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (use of magnetic fields to stimulate brain areas) or from drugs now used for pleasure and exploration, such as LSD. Maybe a decade from now, those with terrible sadness or crippling anxiety will go to their psychiatrist and have a helmet put on their heads that zaps them in just the right way in just the right place. Or maybe a sufferer will be prescribed a course of microdoses of LSD, and this will lead to a profound increase in their happiness and flourishing.

Or maybe the magic drug is ketamine. People who I respect are very enthusiastic about ketamine as a treatment for depression—it’s not just eccentric billionaires and lifehackers. (Check out this discussion of the research of John Krystal, chair of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine.)2 Perhaps the many millions of people who now take SSRIs (about one in eight Americans) will shift to a far more effective treatment involving visiting their doctor every two weeks or once a month and having ketamine administered through a nasal spray.

What about the parts of therapy that don’t involve drugs? There are different types of therapy—such as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Humanistic Therapy, and Psychodynamic Therapy—and these take different approaches. A cognitive-behavioral therapist is likely to guide patients to focus on current maladaptive thoughts and behaviors and is likely to assign “homework.” Such a therapist is less interested in a patient’s dreams or memories of childhood. It’s the opposite for a more orthodox psychodynamic (Freudian) therapist. Still, many—perhaps most—therapists are eclectic, blending together these clinical schools (and, if they are psychiatrists, combining them with medication). Dr. Melfi listened to Tony talk about his dreams and offered him advice on how to deal with his mother and gave him a prescription for Prozac.

Have there been any revolutions in talk therapy? Are there any exciting new developments? I haven’t heard of any, though I’d be interested to hear if there’s anything I’ve missed. If I’m right and there haven’t been, then we can ask, and this is a good topic for a future post: Why not?3

A clinical psychologist friend of mine commented that the best therapists are “lovely, kind-hearted people with good pattern recognition who are skilled in a few powerful experiential interventions.”

Yes, the major researcher exploring how currently illegal drugs can be used in therapy is named “Krystal.”

Some of this post draws on the clinical psychology chapter from Psych: The Story of the Human Mind. I am grateful to Naomi Ball and Rebecca Fortgang for their thoughtful comments on an earlier draft of this post, though they don’t necessarily agree with the general conclusions I draw.

There's a fascinating paper (which I'll try to track down) comparing therapist efficacy in NHS providers in the UK that showed that the best therapists (top 10 percent or so) were vastly better than the median therapist, and then multiple times better again than the absolute dregs (who actually seemed to do harm to their patients). This of course doesn't answer your question at all, because there was no clear explanation for why the best were the best. But it was fascinating on the question of how much difference it makes how good your therapist is. The answer seemed to be not too much in the middle, where the 25% percentile therapist was almost as helpful as the 75% therapist, but a great deal at the top and bottom.

I am reminded of a Phillip K Dick story (actually, I think it was 'do androids dream of electric sheep'), in which everyone had a mood box next to their bed, on which they could dial up the emotional state that they wanted: "I need to feel like going to work" etc. The PKD twist was that the box also needed a setting to make people want to choose a setting. Such a world (A brave new world?!) sounds somehow inherently depressing, which is obviously the point.

While I accept that feelings of depression and anxiety can become pathological, it seems to me that they are, more often than not, normal responses to shitty situations and experiences. I'm not sure that we make the world a better place by banishing them. Your zappy helmet, Paul, causes me some consternation.

I also have concerns about the medicalisation of psychology and our tendency to make diagnoses a part of our identity. I think this is particularly concerning with children. Psychologists have a lot to answer for there. But that is another comment.