"I know it has a 4 in it"

Why our feelings are not to be trusted

A while ago, I wrote a book called Against Empathy that argued that we are often bad at thinking about morality. We tend to be swayed too much by gut feelings, including anger, disgust, and, yes, empathy. We should be more rational if we want to be good people.

My views have shifted a bit since I wrote the book, and in a later post, I’ll discuss some things that I may have gotten wrong. But here, I want to talk about two things I think I got right.

1.

The motivation for this post was a conversation with a friend. He mentioned to me that he had read that more than 40,000 Americans die each year due to guns. Then he hesitated and said,

Wait. Is that right? Maybe it’s 400,000? 4,000? 44,000? I know it has a 4 in it.

We don’t care enough about numbers when thinking about life and death. 40,000 is ten times more than 4,000, an order of magnitude more lives lost, but it doesn’t feel that way. To take this away from a contentious political issue, imagine reading that two hundred people had just died in an earthquake in a remote country. How do you feel? Now imagine you see a correction—the real number was two thousand. Do you now feel ten times worse? What if it was twenty thousand? Do you feel any worse? I doubt it.

The psychologist Paul Slovic explored our insensitivity to numbers in a classic paper (free to download).

My only complaint is with Slovic’s use of the word “numbing.” Yes, moral horrors can render us numb. Kate Manne recently wrote a post called I Have Been So Numb, where she talks about writing a book that explored cases of rape and murder and then describes the effect this had on her.

I could only work on such deeply upsetting topics by deliberately numbing myself to my emotions: anger, fear, sadness, even rage. … The work had to go on. And so I turned myself off.

For me, this is “numbing”. It’s when things are too much to bear, and we shut down. But Slovic is explicit that he is concerned with something different. It’s not that we are overwhelmed when faced with mass death. It’s that we are indifferent.

This is an old insight. In Against Empathy, I quote Adam Smith, who, in 1759, gave this famous example:

Let us suppose that the great empire of China, with all its myriads of inhabitants, was suddenly swallowed up by an earthquake, and let us consider how a man of humanity in Europe, who had no sort of connection with that part of the world, would be affected upon receiving intelligence of this dreadful calamity. He would, I imagine, first of all, express very strongly his sorrow for the misfortune of that unhappy people, he would make many melancholy reflections upon the precariousness of human life, and the vanity of all the labours of man, which could thus be annihilated in a moment. He would too, perhaps, if he was a man of speculation, enter into many reasonings concerning the effects which this disaster might produce upon the commerce of Europe, and the trade and business of the world in general. And when all this fine philosophy was over, when all these humane sentiments had been once fairly expressed, he would pursue his business or his pleasure, take his repose or his diversion, with the same ease and tranquillity, as if no such accident had happened.

It’s not that we are cold-blooded. We care greatly about specific individuals—and not just those we know. A few years ago, the murders of George Floyd and Michael Brown had a profound effect on many Americans. Statistics about drug overdoses—100,000 American deaths per year, most involving synthetic opioids like fentanyl—may leave us unmoved, but the loss of Matthew Perry affected many. The death toll due to guns has a 4 in it, but stories of the shooting deaths of specific individuals, particularly children, can bring us to tears.

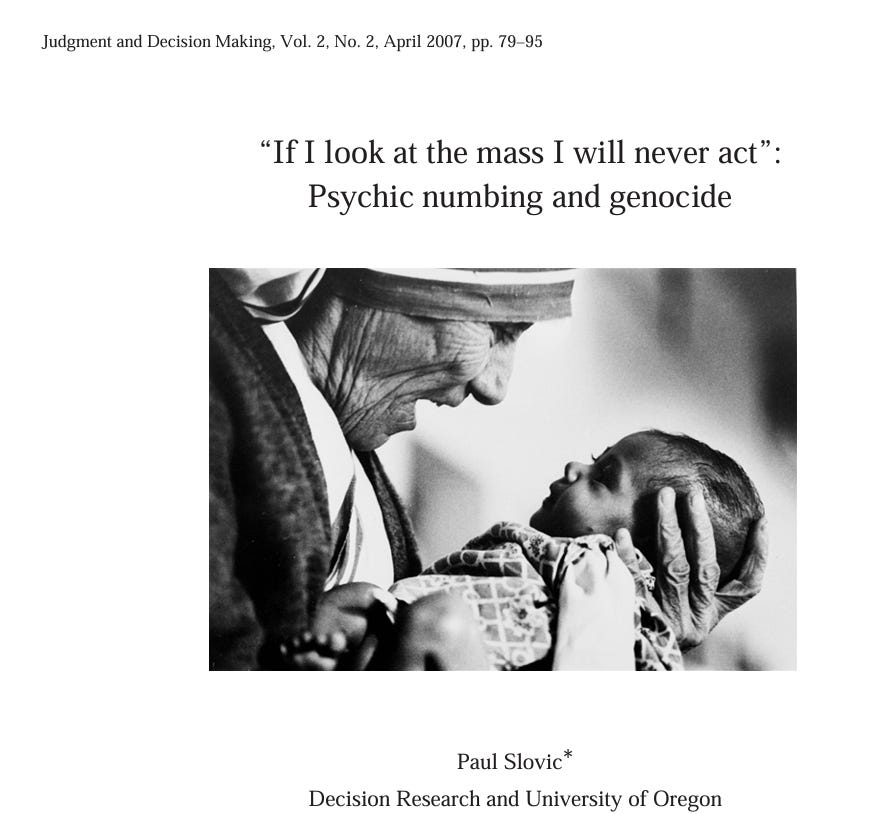

Just as with our indifference to numbers, the greater weight we give to individual lives is old news. Stalin has been quoted as saying, “One death is a tragedy; one million is a statistic.” Mother Teresa once said, “If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.” Slovic quotes the Nobel prize-winning biochemist Albert Szent Gyorgi, on the topic of nuclear war:

I am deeply moved if I see one man suffering and would risk my life for him. Then I talk impersonally about the possible pulverization of our big cities, with a hundred million dead.

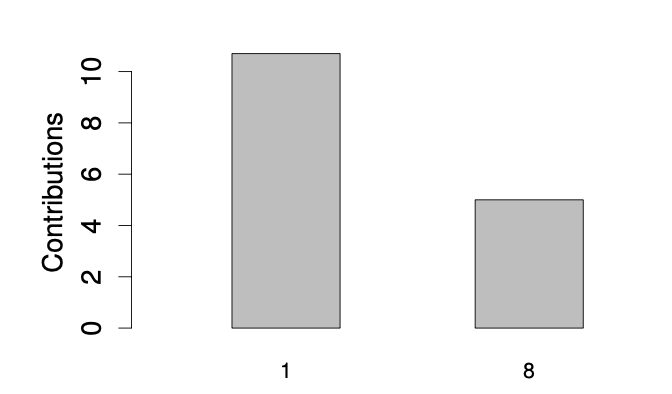

Psychologists have explored our biases in the lab. Slovic reviews the research of Tehilia Kogut and Ilana Ritov, who did several studies on the “identifiable victim effect”. In one study, one group was asked to donate money for a life-saving treatment for a single sick child (and told her name and shown a picture), and another group was asked to donate money for treatment for eight (unnamed, unpictured) sick children. The first group was told that a certain sum of money (about $300,000 USD) would save the one child; the second group was told that the same amount would save the eight.

Did people give more to the eight, appreciating that their donation would make more of a difference? No, it was the opposite.

Maybe you dislike thinking about these matters in terms of numbers. I’ve heard it claimed that an individual life has infinite value, as in the Talmudic saying: “Whoever saves a single life is considered by scripture to have saved the world.” If so, then the numbers don’t matter.

There may be something intuitive to this view—and it might sound very noble—but it shouldn’t be taken seriously. Suppose there is an outbreak of bird flu that could kill hundreds of millions of people. Fortunately, there are vaccines that would save these lives, but these have fatal side effects for some small proportion of people who take them. One vaccine would kill about ten Americans; the other, otherwise identical in its effects, would kill one hundred. You are responsible for choosing which vaccine will be offered to the public. Would you just flip a coin?

The laboratory studies find an appreciation of the importance of numbers when the dilemma is framed in the right way. In the experiment I just described, separate groups of people were asked how much they would donate—one group was asked about a single individual, and the other was asked about 8 people. Presumably, the one-child group gave more because there is an emotional pull here that’s absent for the eight-child group. But if you give the same subjects both options and ask them who they should give more to, people tend to choose to help the eight. Under the right circumstances, we see that eight lives are more important than one.

It makes sense that we have problems with numbers. We have evolved to live in small groups, and our emotional responses are triggered by what happens to the real people we encounter. Natural selection has not wired us up to think in terms of abstractions like “such-and-so number of individuals have died,” and so these statistics leave us cold.

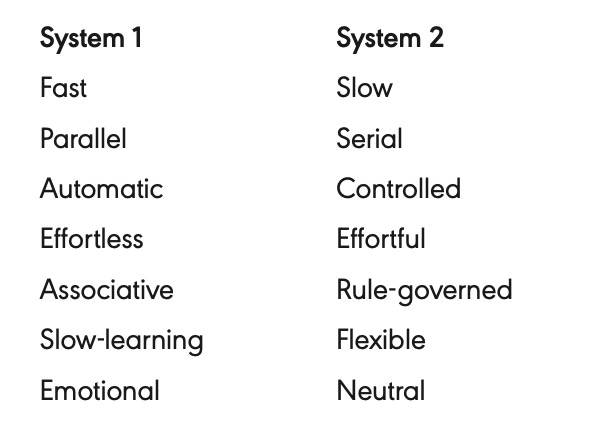

But we can sometimes appreciate the importance of numbers, and this shows that we are not merely emotion machines, ruled by our gut feelings. We are capable of thinking abstractly, at least under some circumstances. Philosophers and psychologists have long argued for a duality of human thought, arguing that the mind contains two distinct systems, sometimes called “System 1” and “System 2”, and these have the following properties.1

System 1 is what gets us into the fix that Slovic worries about. It responds powerfully to the fate of salient individuals and is unmoved by numbers. But System 2—slower, effortful, under conscious control—allows us to reflect, to think more carefully, to appreciate that the death of 40,000 is so much worse than the death of 4,000, and the suffering of 8 matters much more than the suffering of one.

2.

How do you get people to think clearly about what matters? My answer, and Slovic’s as well, is to get people to use their System 2, to employ what I call “rational compassion.”2

But there’s a different answer, one that’s very popular. We can influence people to do the right thing through vivid stories of individual suffering, stories that hit us right in System 1. Slovic quotes the novelist Barbara Kingsolver:

The power of fiction is to create empathy. It lifts you away from your chair and stuffs you gently down inside someone else’s point of view. ...A newspaper could tell you that one hundred people, say, in an airplane, or in Israel, or in Iraq, have died today. And you can think to yourself, “How very sad,” then turn the page and see how the Wildcats fared. But a novel could take just one of those hundred lives and show you exactly how it felt to be that person rising from bed in the morning, watching the desert light on the tile of her doorway and on the curve of her daughter’s cheek. You could taste that person’s breakfast, love her family, and sort through her worries as your own, and know that a death in that household will be the end of the only life that someone will ever have. As important as yours. As important as mine.

… Art is the antidote that can call us back from the edge of numbness, restoring the ability to feel for another.

Slovic adds:

Although Kingsolver is describing the power of fiction, nonfiction narrative can be just as effective. The Diary of Anne Frank and Elie Wiesel’s Night certainly convey, in a powerful way, the meaning of the Holocaust statistic “six million dead.”

… Vivid images of recent natural disasters in South Asia and the American Gulf Coast, and stories of individual victims, brought to us through relentless, courageous, and intimate news coverage, certainly unleashed a tidal wave of compassion and humanitarian aid from all over the world. Private donations to the victims of the December 2004 tsunami exceeded $1 billion. Charities such as Save the Children have long recognized that it is better to endow a donor with a single, named child to support than to ask for contributions to the bigger cause.

An image that sticks with me is an article in Time magazine from August 9, 2010, about the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan. Instead of giving statistics, they focused on the story of Aisha, an 18-year-old Afghan woman. She had run away from her husband’s abusive family, and the Taliban cut off her nose and her ears. Time put a picture of her disfigured face on the cover of their magazine. (If you want to see it, and read the accompanying article, it’s here.)

I don’t doubt that these appeals to empathy, this focus on individual lives, can make a positive difference. The stories of the suffering caused by the tsunami really did generate a lot of donations. The Time magazine article made me, and many others, care about what was happening in Afghanistan; it was more powerful than any dry list of statistics.

But I’m not optimistic that this System 1 appeal is the way to get our moral priorities straight.

For one thing, we are most drawn to stories that appeal to our biases. Slovic again:

According to the Tyndall Report, which monitors American television coverage, ABC news allotted a total of 18 minutes on the Darfur genocide in its nightly newscasts in 2004, NBC had only five minutes, and CBS only three minutes. Martha Stewart and Michael Jackson received vastly greater coverage, as did Natalee Holloway, the American girl missing in Aruba.

And:

One of the most publicized events occurred when an 18-month-old child, Jessica McClure, fell 22 feet into a narrow abandoned well shaft. The world watched tensely as rescuers worked for two and a half days to rescue her. Almost two decades later, the joyous moment of Jessica’s rescue is portrayed with resurrection-like overtones on a website devoted to pictures of the event.

(One such picture is at the top of this post.)

The cynical view is that journalists are giving people what they want—no American would watch a network that covered the Darfur genocide for hours each day. But a more charitable perspective is that journalists are people too. They focus on Natalee Holloway and Jessica McClure for the same reason that their viewers and readers want to see stories about Natalee Holloway and Jessica McClure—because, for them as well as us, the suffering of those who look like us and those we love are what capture the focus of System 1. The one matters so much more than the many.

One response to this is: Well, at least these stories do some good! Maybe they move us in ways that don’t perfectly align with our thought-out priorities, but they are a force for compassion and kindness.

But this isn’t always the case. It’s a mistake to see empathy as a moral force. It is a tool, and like any tool, it can be used for good or evil. Here is the critic Joshua Landy discussing this in an unpublished paper (quoted with his permission).

For every Uncle Tom’s Cabin there is a Birth of a Nation. For every Bleak House there is an Atlas Shrugged. For every Color Purple there is a Turner Diaries, that white supremacist novel Timothy McVeigh left in his truck on the way to bombing the Oklahoma building. Every single one of these fictions plays on its readers’ empathy: not just high-minded writers like Dickens, who invite us to sympathize with Little Dorrit, but also writers of Westerns, who present poor helpless colonizers attacked by awful violent Native Americans; Ayn Rand, whose resplendent “job-creators” are constantly being bothered by the pesky spongers who merely do the real work; and so on and so on.

And here’s me, writing in Against Empathy about anti-immigrant rhetoric by a certain presidential candidate.

When Donald Trump campaigned in 2015, he liked to talk about Kate—he didn’t use her full name, Kate Steinle, just Kate. She was murdered in San Francisco by an undocumented immigrant, and Trump wanted to make her real to his audience, to make vivid his talk of Mexican killers. Similarly, Ann Coulter’s recent book, Adios, America, is rich with detailed descriptions of immigrant crimes, particularly rape and child rape, with chapter titles like “Why Do Hispanic Valedictorians Make the News, But Child Rapists Don’t?” and headings like “Lost a friend to drugs? Thank a Mexican.

If you want to stoke hatred towards a group, a good trick is to get people to feel empathy towards those described as harmed by that group. The passage above about Trump was written in 2015, but it’s not like these sorts of stories have fallen out of fashion. Here are some headlines posted on the Twitter feed of Trump advisor Stephen Miller.

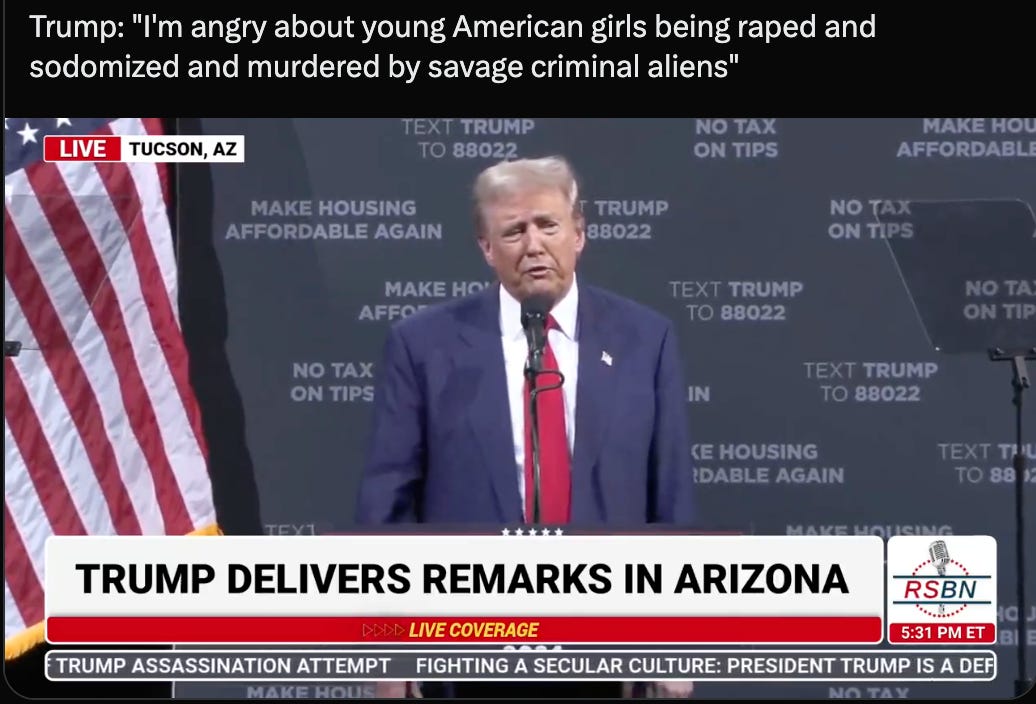

And here is Ex-president Trump, from a recent rally.

This is what empathic persuasion often looks like.

This sort of storytelling will never go away. Before writing this, I was lying on my bed, looking at my Twitter feed, the email news summary from the NYT, and a few substacks. Most of what I read was stories, often of suffering. Rapes in Darfur. Mutilated children in Gaza—and the torment of the Israeli hostages held by Hamas. Immigrant crime. Crimes against immigrants. Someone being unjustly imprisoned, another losing her job, a victim of obstetric assault, and so on.

Stories are how we communicate. I use stories all the time in this Substack—to amuse, to illustrate, and to persuade. And it’s hardly illegitimate to use stories to draw our attention to the suffering of individuals. This has moral weight; it’s worth knowing about.

But we are making a terrible mistake when we let the details of the stories and the skill of the storytellers determine what we judge to be most important. The American toddler stuck in a well is much more moving to most of us than many thousands dying of famine in a distant country. But it’s really not more important. The lurid tales of victims of crimes can stir up our hatred, but we’re better off looking at the actual statistics. We are more moral people—kinder, more compassionate, more just—when we are wary of the storytellers, and when we work hard to use our System 2.

This System 1/System 2 terminology was introduced by the psychologists Keith Stanovich and Richard West in this 2000 article. Daniel Kahneman provides an excellent overview of this distinction in his book Thinking Fast and Slow.

Easier said than done, of course. Both Against Empathy and Slovic’s articles have some concrete proposals, and I hope to explore this more in a future post.

Reminded of a line from Bertrand Russell: “the mark of a civilized human being is the ability to read a column of numbers and weep.”

I agree entirely with the suspiciousness towards empathy, while acknowledging its value as a tool (AND, let's not forget, a likely evolutionary basis for morality overall -- but we should be beyond relying on that now!). And yet. And yet.

I wonder if the whole effect isn't exacerbated nowadays with the individual feeling of helplessness though, in the face of mass suffering, death and even genocide. Focusing on one (perhaps plucked FROM the relevant number) might allow us to do something, instead of feeling it's all pointless altogether because we not only cannot save them all, we cannnot even save a significant proportion: and yet the saved ones ARE saved, like in the story of the child on the beach throwing starfish back into the sea. It matters to them.

So, perhaps the best way to use individual empathy for good is to tell (or learn) a story of one, to hook the reader (or yourself) but to follow on with decisions based on numbers?