How to give a better-than-average talk

13 tips

When I was in graduate school, I couldn’t make it through most of the talks presented in my department. I got bored and frustrated and tuned out. It was before smartphones, so I would doodle or fall asleep.

I figured it was my fault. Maybe, in part, it was—my attention span is not my strong suit. But I’ve heard a lot of talks since then, including many wonderful ones, and I’ve worked hard on improving my own presentation style. And I now think that it wasn’t just my fault. Most talks are bad—boring, hard to follow, and poorly delivered.

So here’s some advice on how to give good talks. Not great ones, perhaps, but at least better than average.

Public speaking is stressful to many people and a “how to” list might add to the stress, so I’ll add one thing: The audience is your friend. They want you to give a good talk. This is because most people are kind, and also because a good talk is in their own interests. They want to spend the next 20 or 30 or 60 minutes being informed, challenged, amused, and so on—and hope very much you will succeed at doing this. If they feel like you are working towards that end, that you want this too and are trying your best, they will forgive your slip-ups and cheer on your successes.

1.

There is no such thing as a good talk for every occasion. There are different sorts of talks, and what’s good for one audience might be terrible for another.

Psychologists almost always use presentation software such as PowerPoint.

Psychology job talks usually end with a discussion of future directions.

Philosophers used to slowly read their talks from manuscripts that they held in front of them. I was once at a talk at MIT where the manuscript was distributed ahead of time and the audience read silently along with the philosopher. (I know this sounds made-up but it’s true.) Now their talks are often more like those of psychologists.

TED talks often begin with the speaker staring solemnly at the crowd and then telling a story. The talks are short, accessible, avoid complexity and ambiguity, and sometimes end with a call to action or some inspiring message.

At various points in their talks, politicians pause for applause.

Criminal masterminds often stop their talks in the middle, kill someone or have one of their henchmen kill someone, and then keep on talking as if nothing ever happened. When a Mob boss begins by pointing to his lieutenants and saying “One of youse is a rat!”, violence is sure to follow.

Wedding speeches by friends of the bride or groom are given when drunk (or seemingly drunk). There is laughter, allusions to dirty stories, and sometimes tears. They end with a toast.

The advice: To learn to give a good talk, you need to know how talks in that genre work. Giving a TED talk? Watch a dozen TED talks. If you’re a graduate student about to go on the job market, go to job talks in your own department. (Focus on bad ones; often they teach you more than good ones.) If you’re new to a lab and you’re asked to give a talk, try not to go first—watch other talks, and get a sense of local custom. I was the MC at my sister’s wedding and I got a book called “How to Be a Great Wedding MC” and watched several YouTube videos.

I have failed to follow this advice in the past. A long time ago, I was asked to give a talk for One Day University and they wanted something fun for a general audience of mostly retired people. I gave a simplified version of a colloquium talk. The old people were bored, and I apologized later to the organizers.

Many years later, I made the opposite mistake. Pumped up after having just given a TED talk, I gave a too-casual presentation to an audience of hostile philosophers—and boy did I get my ass handed to me.

Now, once you know the conventions, you can choose to break them. Malcolm Gladwell once presented at a social psychology speaker series at Yale. He spoke with no slides (!) and no notes (!!) and took only 40 minutes (!!!). And it was terrific. Many psychology colloquia begin with a review of the literature but for a talk I gave on word learning many years ago I decided that there was a better way. I started by presenting my most exciting finding—in media res works for movies, why not talks?—and then I doubled back and reviewed the literature. People seemed to like it.

You can break the rules, then—but best to know what the rules are first.

2.

To become a good speaker, it helps to get advice. This is harder than it seems, particularly when you’re no longer a student. You’ll get a lot of feedback on whatever it is you’re talking about (often getting this feedback is the main point of giving a talk), but when it comes to the presentation itself, you’ll usually just get either a “nice talk” or nothing. You have to seek out advice.

It might hurt. What we all really want, always, is: “Absolutely perfect—don’t change a thing.” As a new professor, I asked a friend if she had any comments on a colloquium I just gave, and she said immediately: “You wave your hands like a crazy man and it’s hard to pay attention to anything you’re saying.” Good to know, but I was stung, and for the next several talks, I thought of nothing but my hands. But now, watch me—no more crazy man hands.1 Get advice.

3.

To give a good talk, practice. This is time-consuming and boring, but it will make you sound so much better. You’ll find mistakes and ideas for improvement that you’ll never have discovered any other way.

There are stories about people who don’t need to practice, who glance at some notes, and then hop on stage and give amazing presentations. Good for them. I’m not one of these brilliant freaks and, if you’re reading this, you probably aren’t either.

4.

Always go shorter; always prepare a talk that takes less time than you have allotted. You don’t want to go over time or have to rush at the end. People are often irritated when a talk goes over time; nobody has ever complained about a too-short talk. I’m not suggesting a 10-minute talk for a 50-minute slot—but 45 minutes is a lot better than 55 minutes.

For academic talks, people really like them short, because they want to get to the discussion period and get the chance to talk themselves.

5.

Always go simpler. You’re used to these ideas, you’ve thought about these studies for months or years, and you’ve forgotten how complicated it all is. Many speakers will run through their material too quickly and lose their audience. Take your time. Give an example and then give another one. Just as nobody has ever complained that a talk was too short, nobody has ever complained that one was too clear.

6.

But … don’t stop to ask your audience if they understand what you’re saying. I don’t want to be unkind about it, but you’re then at the mercy of the dumbest person in the room. Things can get derailed, and you risk not finishing on time. Just be clear in the first place.

What about audience participation more generally? Some speakers invite it, asking people to raise their hands if they think the top line is longer than the bottom one (for a perception talk) or asking how many in the audience believe consensual incest between adult siblings is morally wrong (for a morality talk). That can be fun and break the monotony of a long presentation. But I am wary of anything that risks having audience members derail things—a show of hands is much better than “any thoughts?”

(There are exceptions here. Some small presentations, like a lab talk, are more like seminars and have a more conversational nature. In some departments, there is a custom of interrupting with long questions and you have to be a good sport about this, even if, like me, you hate it.)

7.

The best talks include stories. This has become a bit of a cliche—see my description of TED talks above—but, really, narratives are fun and they stick in people’s minds. (This is true for writing as well; Earlier, I told you stories about talks I gave at One Day University and to a group of philosophers, and I bet you remember both of them.)

Many good talks are stories. Research talks are often the story of how the speaker was interested in a problem, and, over a series of experiments, each building on the next, it was solved. It’s the story of an investigation and in the right hands, it can tickle the same feeling of delight in the audience that they would get if they were hearing about how someone tracked down a serial killer.

8.

For long talks, make them oniony. Herman Havercort distinguishes two types of talks.

The clew [ball of thread] is a logical, linear argument building up to a conclusion at the end of the talk, like a clew unwinding until you finally come to the core. Miss one step in the talk and you lose the plot and miss the point. And yes indeed, this is exactly what happens when I listen to most conference talks and some lectures. In a three days' conference, I actually follow the first five minutes of one or two dozen talks. That is more or less it. After those five minutes, I get lost. …

The onion talk starts with the main message, and adds depth in successive layers around it, always returning to the main message between layers. Since the main message and the main ideas are repeated often, a listener can still follow most of the talk even after dozing off for a minute. Also the talk does not get screwed up near the end when the speaker is running out of time, because by then, the most important things have been said already and the speaker has no reason to hurry.

I tend to give onion talks myself, at least for longer presentations. I have a big idea, and I explore it from different directions, giving examples, responding to critiques, and so on. Doze off for a part, you can pick up the next.

But I’m not sure this is the best sort of talk. My reliance on it might be one of my biggest weaknesses as a speaker. The problem with the onion talk is that it conflicts with the piece of advice just above—to tell a story. The onion has no narrative flow. When Havercort complains that if you miss a step in a clew talk, you’ll lose this plot, he’s right, but this is true as well for novels and movies and television, and people love these things. And if the talk can flow really well, with one part naturally connecting to the next, then people won’t get lost or bored. A great story is better than an onion.

But an onion is better than a talk that’s hard to follow. My suggestion here is to make your talk oniony. Try as best as you can to stick to the narrative and tell stories throughout, but use outlines, interim summaries, overall reviews, and so on, so that someone who loses the plot can get back on track. Like: “So we’ve seen that Blah Blah. But you might be wondering what So-and-So would say about my claims”, and then the dozy listener who missed the whole Blah Blah part can get back on board for the So-and-So part.

None of this is needed for a short talk. You don’t need to say what you’re going to say or what you just said. Just say it. No onion, all clew.

9.

Make slides that don’t suck. I don’t have much of a design sense myself and have nothing to say about serif versus sans-serif or light-on-dark versus dark-on-light. If you’re interested, there are a lot of places to go for specific advice on fonts, colors, placement of pictures, and so on. I recommend this book—Presentation Zen.

But I’ll just make the obvious points here. Make your font really big, use as few words as possible, and avoid clutter.

A psychologist who is one of the best speakers I’ve ever seen—and who now uses wonderful slides—gave me permission to show a PowerPoint slide from a presentation she gave as an undergraduate. It’s so ugly that it looks like it was done as a prank, but, no, she really showed this to actual people.

But I have seen ones almost this bad, by tenured professors.

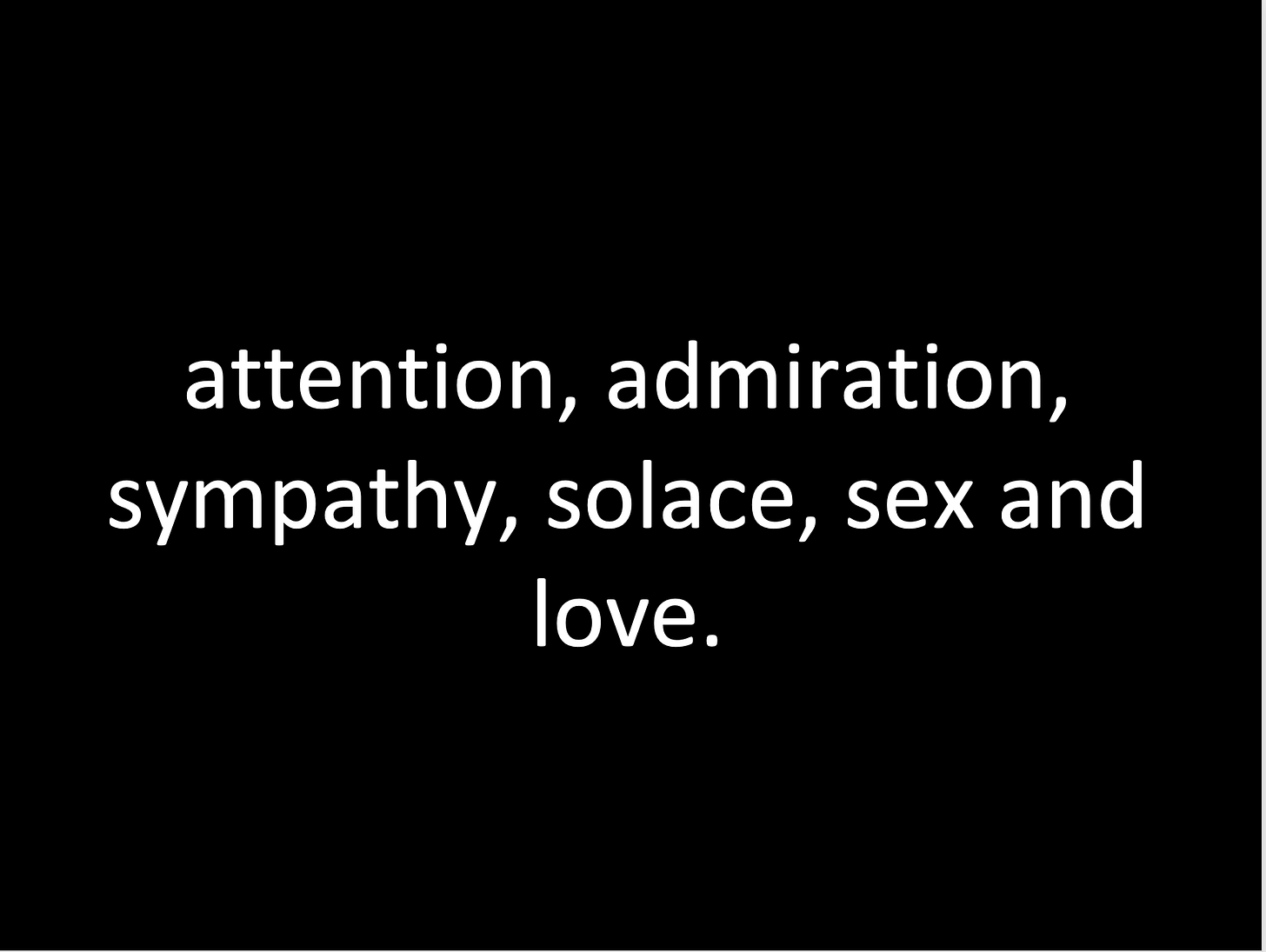

Here’s one of mine. I’m sure it could be better (do I need the period? Would black-on-white be easier to read? Is the whole look too harsh and minimal?), but at least you can read the damn thing.

You often don’t need slides. If you’re a really gripping speaker, you can just talk. But I like them. I like being able to display pictures, put up a quote, show what my collaborators look like, or walk through an outline. And, like a lot of people, the slide deck reminds me what I’m going to say as the talk proceeds, so I don’t have to memorize too much or use notes.

Slides are necessary if you want to show graphs, figures, diagrams, that sort of thing. There is often a challenge here. I’ve seen many speakers put up a sea of tiny numbers, wave their hand at it, and say something like “Yeah, sorry, I know this is really hard to read.” This is the point where I take out my phone and check my email. You need to use various tricks—like zooming in on a few numbers, or shading parts of a graph while blacking out the rest—to help out your audience here.

10.

Credit the people in the room. For an academic talk, if there are people in the audience who work in the area you’re talking about, be sure to mention them at the relevant points. (Some of them will spend the talk waiting to hear their name.) If you’re unsure about attribution, wave your hand at the audience occasionally, and say something like “Of course, I know there are people here who know a lot more about this than I do,” and with luck, the right people will assume you’re talking about them.

11.

If there’s a microphone, use it. If the room is on the smaller side, you might be tempted to just talk louder, but the microphone will sound better and make life easier for those with hearing impairments. Clip-in mikes are best because you can pace around, but if they don’t have one, follow the advice of Adam Mastroianni and hold the mike very close to your mouth, about three inches. (Good advice also for Zoom talks.)

12.

Don’t just start the talk. Say something like “Thanks for the nice introduction” or “Nice to be here” so that the audience has a moment to get used to your voice, and you can modulate your volume and tone if necessary.

13.

Always make it clear when your talk is over, so people know when to applaud or raise their hands. The usual way is to say “Thank you.”

Thank you.

My wife read an earlier draft and she told me that, while my hands are normal when I give a talk, I now have the distracting habit of swaying back and forth. Damn.

As one of those freaks—brilliant is too far a stretch—who is great at giving talks without much prep (but awkward one-on-one haha), I would have you know that I'm reading this because YOU wrote it, and not for any other reason. Your writing is always crisp, concise and informative. I never feel like you're talking at me, but rather, with me. Thank you for being such a delightful read, and your pointers are practical and apt. It's also awesome that you know and are committed to improving your perceived weaknesses. Your latest TED Talk was 👌 and hit the sweet spot. Cheesy pun totally intended!

Excellent advice. I’ll have to try to find expertise and an audience, then I’m on my way! I wish this had been put so succinctly years ago (it may have been, but I missed it or it me). Thank you.