Assistant to the Regional Manager

The problem with utopia

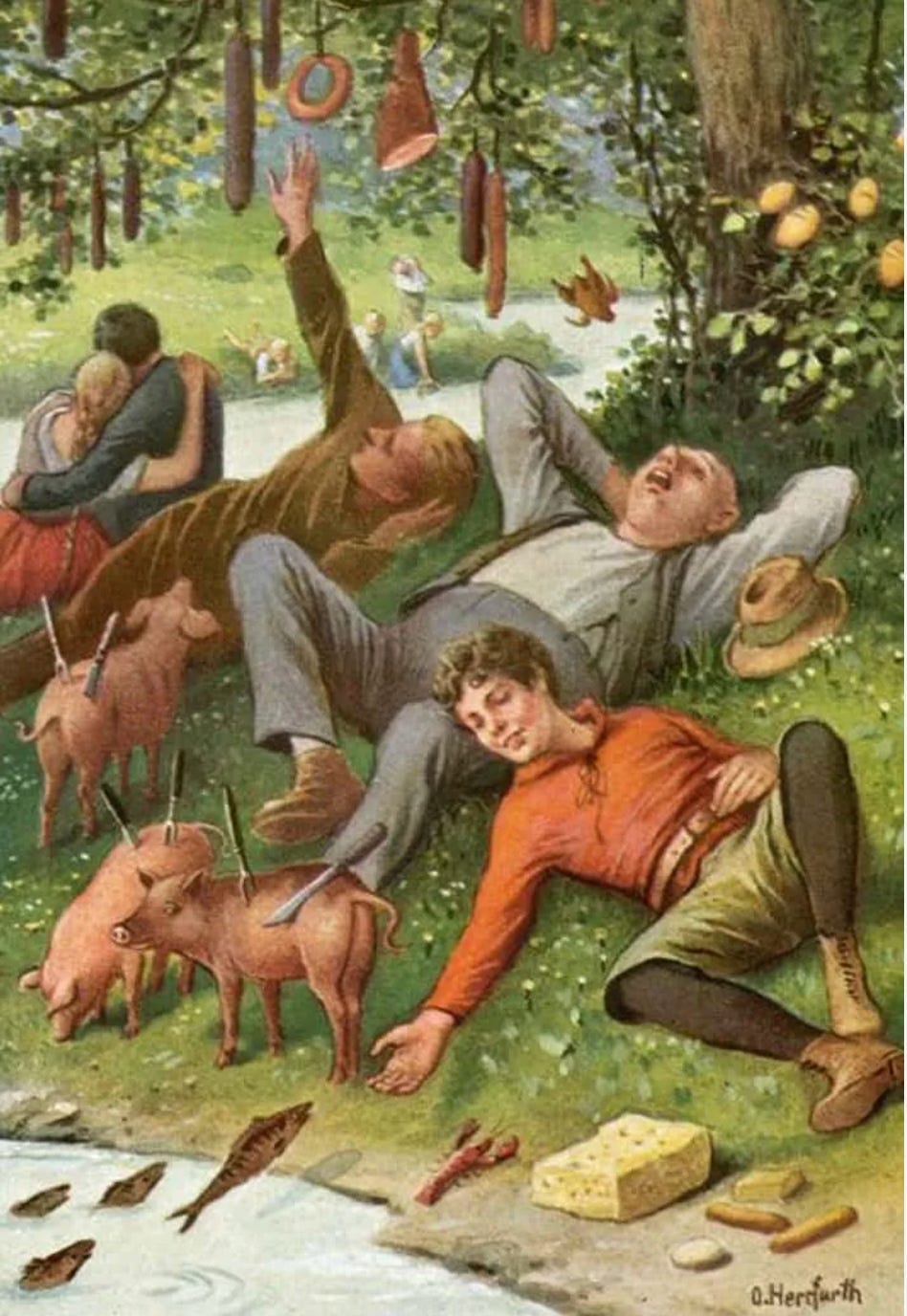

If you’re hungry, utopia is an all-you-can-eat buffet. Take it from the 13th-century French poem The Land of Cockaigne, as described in Nick Bostrom’s excellent book Deep Utopia.

In the land of Cockaigne, there is no backbreaking labor under scorching sun or nipping north wind. No stale bread, no deprivation. Instead, we are told, cooked fish jump out of the water to land at one’s feet; and roasted pigs walk around with knives in their backs, ready for carving; and cheeses rain from the sky. Rivers of wine flow through the land.

Bostrom goes on to point out that many of us now pretty much live in such a world. We tap on our phones, and someone quickly comes to our door with lemonade, fish, sausage, or cheese.

What would it be like if everyone had unlimited access to food and drink? What if we were done with material deprivation together—if we all had nice houses, access to the best medical treatments, the best childcare, and so on? And what if we didn’t have to work for any of this—we could spend our lives however we please?

The obvious point first: Such a world would be wonderful. There are people now who are starving, who watch their children die due to lack of clean water or medical care, who spend their days at backbreaking or humiliating labor. Even those of us who are relatively well-off often worry about meeting our own needs and the needs of those who depend on us, and many of us work at jobs that we don’t like. To be released from the yoke of all this struggle and anxiety would be so fantastic that we should feel a bit uncomfortable talking about the downsides.

And yet. Many people are interested in utopia these days, prompted by the promise of AI, and one worry keeps surfacing.1 It’s often said that if all our needs are satisfied, we would suffer from ennui and loss of purpose. Struggle is what gives life meaning, and in a post-scarcity utopia, there would be no struggle.

I agree that a good life involves struggle and some degree of suffering. In fact, I agree so much that I wrote a book about it.

But I think this won’t be a problem with a post-scarcity world. So many of the difficulties we face in life stem from our interactions with other people, and these won’t go away even with infinite material resources. So long as we remain human, we can never be fully satisfied.2 On the bright side, our lives will continue to have meaning in a post-scarcity world. We might be miserable, but we won’t be bored.

Before making this argument, I want to defend the topic. Utopia is not around the corner; these issues don't have any practical urgency. But I agree with Bostrom that thinking about utopia “can serve as kind of philosophical particle accelerator, in which extreme conditions are created that allow us to study the elementary constituents of our values.” Reflecting on utopia might tell us something interesting about human nature more generally.

When I was just starting off as a new Assistant Professor at the University of Arizona, I wandered through the halls, knocking on doors and talking to my new colleagues. And I remember meeting this old professor, and after we talked a bit, he told me, without being prompted, that he was a tenured Associate Professor, but had never been promoted to Full Professor.

I asked: "What do you get from being a Full Professor?" A bump in pay? No, he said. More research funds? No, he said. In fact, he admitted, if he were promoted, he’d have to be on more committees, and he hated committees. And then he went quiet and just stared at his desk, and when he looked up at me, I saw that his eyes were wet with tears.

Now I get it. In the years since, I have lost out on awards and honors that were as symbolic as the promotion that my colleague was denied, and I know how much it hurts. And I remember how proud I was when the president of Yale called me into his office and told me that I was going to become a named professor (Bump in pay? No. More research funds? No.). I also remember how resentful one of my colleagues was for not becoming a named professor himself.

This is all easy to mock. There is a running joke in the U.S. version of The Office where Dwight Schrute (Rainn Wilson), who is “Assistant to the Regional Manager” keeps insisting that he is “Assistant Regional Manager”, which sounds a bit better. When he is officially promoted to the title he prefers, he is delighted—see here:

Titles mean something because they mark one’s status—where one stands relative to others. There are many such “positional goods”. If everyone could get a degree from Harvard, its value would diminish greatly because it would no longer signal that the degree-holder is special. If everyone could afford a Rolex or own an original Picasso, a lot fewer people would want a Rolex or an original Picasso.

Positional goods matter. Our desires are shaped by a hunger to exceed what others have, or at least to match them—and definitely not to drop below them. This can lead to a ratcheting effect, where once some people acquire a publicly observable scarce resource, such as a larger-than-usual house, it puts pressure on everyone else to follow suit. Writing ten years ago, the economist Robert Frank gives the example of weddings.

Like a good school, a "special" celebration is a relative concept. To seem special, it must stand out from what people expect. But when everyone spends more, the effect is merely to raise the bar that defines special. The average American wedding now costs $30,000, roughly twice as much as in 1990. No one believes that couples who marry today are happier because weddings cost so much more than they used to.

Money itself can be a positional good. It’s not only how much you make that counts, but how much you make relative to those around you—those you are comparing yourself to, those whose respect you want. H.L. Mencken was onto something when he wrote that “A wealthy man is one who earns $100 a year more than his wife’s sister’s husband.”

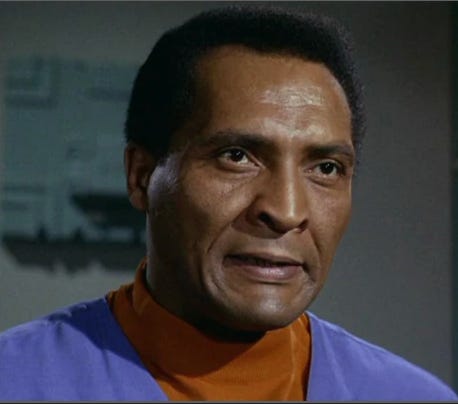

Now, a post-scarcity world probably won’t have money. The United Federation of Planets in the Star Trek world doesn’t. But it’s full of positional goods. Not everyone gets accepted to Starfleet Academy, not everyone graduates, and not everyone gets to be captain of a starship or a similarly impressive high-ranking position. (Do you think parents in the 24th century are going to want their children grow up to be red-shirted security officers?) In the Star Trek world, there is often talk of esteemed scientists, artists, and diplomats, which implies that there are average scientists, artists, and diplomats—and, sadly, it means there must be at least some really shitty, bottom-of-the-barrel scientists, artists, and diplomats. It must hurt to be part of that group. The inevitability of hierarchy, that some people will do better than others and be more respected for it, leads to all sorts of social pleasures and social pains.

The writers of science fiction are well aware of this. In an episode of the original Star Trek, we are introduced to Richard Daystrom, a scientist brought aboard the Enterprise to test an advanced AI that could control a starship by itself, rendering a human crew superfluous. (Timely!). Daystrom is brilliant—a Nobel Prize winner who made his most important discovery at 24. He never managed to top this early success, though, and grew bitter over what he felt was a lack of appreciation for his more recent work. (Things do not go well with his AI creation, and Daystrom ends the episode being sent to an institution.)

In Iain M. Banks's Culture novels, there are no material needs and little personal property. But then people strive to distinguish themselves in other ways, such as skill, daring, and creativity. And so being good at games becomes of great importance, the source of great pleasure and pain.

Some readers are nodding, others are rolling their eyes. Assistant to the Regional Manager! I don’t care about that! In a post-scarcity world, I’ll enjoy the freedom to do whatever I want, and I wouldn’t care at all about what anyone thinks of me.

Status and respect do matter more to some people than others, and some are unconcerned about the hierarchies that others value. I know many professors who care deeply about accumulating awards and honors, but I also know a few who don’t, including one who really doesn’t want to be promoted to Full Professor, because she sees it as a silly honor, and would find the additional committee work to be a pain in the ass.

But I’ve never met anyone who was entirely indifferent to the opinions of others. Maybe it’s not important to be the best, but it usually stings to be thought of as the worst. More than that, everyone has some aspects of their lives where they want to be thought well of. Maybe they don’t care about being Assistant Regional Manager, Full Professor, or a respected Player of Games. But they would be deeply hurt if people thought of them as a below-average parent, one of the worst writers on Substack, or their least-interesting friend.

One of the good things about the modern world is that there are many hierarchies, and so many opportunities to do well, or at least not to totally suck. Will Wilkinson put it like this:

The cultural fragmentation some critics lament is precisely what liberates us from unavoidable zero-sum positional conflict. Surfer dudes don’t compete with Star Trek geeks for status.

In an article published in the Boston Review on status and luxury goods, I elaborated on this point, writing:

My neighbor has a Rolex and a Ferrari, so he is richer, but my children are better looking and better behaved. He is more fit, but I’ve published in Boston Review.

I admit that there’s something a bit unseemly about talking about titles, hierarchies, and status, and it’s understandable that some of us don’t want to admit to caring about such things. But the point can be put in a broader, more respectable way. A new book by Rebecca Goldstein called The Mattering Instinct explores the universal desire to matter, to be of significance. Goldstein defines mattering as

to be deserving of attention

Wanting to matter is a more respectable ambition, but, again, the problem here is that attention is a scarce resource, yet another positional good. If I matter a lot to my niece—she likes me, she thinks I’m a cool uncle—it’s a source of joy to me. But not everyone can matter to her to the same extent; she can have only one favorite uncle, and, indeed, part of the joy of mattering is being special. Some people matter more than others, to the world at large and to their friends and family. And some don’t matter at all, which must feel horrible.

I don’t think status, respect, and mattering are the most important things. Air is more important. Take away someone’s air, and they won’t be worrying about where they stand in a status hierarchy; they won’t obsess over how much they matter. Food is more important, and water is more important. But then its status, respect, and mattering that matter the most.

A related problem with utopia has to do with sexual desire. One might think that the sorts of utopias that people talk about can solve the problem of lust, with immersive VR porn and sexbots and the like. And yes, such technological innovations would scratch a certain itch—the simple desire for sex with someone (something?) sexually desirable. The opportunity for anonymous coupling is a big feature of the utopia depicted in The Land of Cockaigne, where we are told that monks get to have sex with hot young nuns, so that a lucky monk “can easily have twelve wives each year.”

But, of course, there’s more to desire—we are often attracted to a particular person. We want them; we covet them. It’s wonderful if they covet us back; it’s agonizing if they don’t. To make things worse, even if we’re lucky enough to arrive at reciprocal desire, we often want the other’s desire to be exclusively pointed our way. They not only should want to have sex with us; they should not have sex—and perhaps should not even want to have sex—with anyone else.3

And so one person’s satisfaction is contingent on the choices of another. If things don’t work out, there is no good solution. Either the person who is attracted has their desires frustrated, or, worse, the person who is the target of the attraction is coerced into a sexual relationship (possibly an exclusive one) that they don’t want.

Attempts to create Utopian communities have always struggled with the problem of sex. Some, like the Shakers, did their best to emulate what they see as our fate in heaven, and banned non-procreative sex altogether. Others, like the Oneida Community, founded by John Humphrey Noyes in 1848, practiced “complex marriage” where everyone was considered to be married to everyone else—monogamy was seen as a form of idolatry that detracted from one’s devotion to the community. None of this worked.

I’ve framed this as an issue about sex, but of course it applies more broadly. We fall in love with people who aren’t in love with us; we want to be best friends with people who don’t want to be best friends with us, and maybe don’t even like us. It’s the problem of mattering all over again; we want to matter to other people in a certain way, but the savage reality is that they might not feel the same way as we do.4

Scarcity generates pleasure, anxiety, and purpose. But a world that is post-scarcity in the sense that there is more than enough material resources for everyone will still have another form of scarcity—people’s respect, admiration, attention, desire, and love.

The bad news about a post-scarcity utopia is that we will still be unhappy much of the time. The good news is that our lives will still have meaning.

As a recent example, check out this interesting discussion between Sam Harris and Ross Douthat. (Sorry, paywalled).

I should explain the qualification “So long as we remain human”. When I think of utopia, I’m assuming a post-scarcity world where all of our material needs are met, along the lines of Star Trek or Banks’s Culture novels. In Bostrom’s book, he considers more extreme scenarios. We might all ascend to a nirvana-like state where there are no desires. We might have the parts of our brain that connect to suffering and boredom surgically ablated. Or we might all be hooked up to machines, Matrix-style, ensuring that our conscious existence is that of a continuous, intense orgasm intermixed with the feeling of total, limitless love.

All of this gives me the creeps myself. But, anyway, the arguments here apply only to utopias where human nature and human experience remain pretty much unchanged.

Everything else I’ve been talking about here is a human universal, but I’m less sure about sexual jealousy. I know a few people who don’t care (or claim not to care) if their partner has sex with other people. If we are malleable in this way, and can outgrow our possessiveness, perhaps sexual and romantic jealousy won’t be a problem with a post-scarcity utopia. But the other problems, including the big one that we sometimes desire people who don’t desire us back, will remain.

What about AI companions? If you fall in love with your AI, you’re in luck—it will love you back, or at least act as if it loves you back. I think there are ways in which a relationship with an AI is deficient to that of a human (see here), but, anyway, even in a world with powerful AIs, some of us will presumably fall in love and be attracted to actual people.

I was recently rereading Paul Graham's essay on why high school is so miserable. Graham writes:

"It's no wonder, then, that smart kids tend to be unhappy in middle school and high school. Their other interests leave them little attention to spare for popularity, and since popularity resembles a zero-sum game, this in turn makes them targets for the whole school. And the strange thing is, this nightmare scenario happens without any conscious malice, merely because of the shape of the situation.

...

Why is the real world more hospitable to nerds? It might seem that the answer is simply that it's populated by adults, who are too mature to pick on one another. But I don't think this is true. Adults in prison certainly pick on one another. And so, apparently, do society wives; in some parts of Manhattan, life for women sounds like a continuation of high school, with all the same petty intrigues.

I think the important thing about the real world is not that it's populated by adults, but that it's very large, and the things you do have real effects. That's what school, prison, and ladies-who-lunch all lack. The inhabitants of all those worlds are trapped in little bubbles where nothing they do can have more than a local effect. Naturally these societies degenerate into savagery. They have no function for their form to follow.

When the things you do have real effects, it's no longer enough just to be pleasing. It starts to be important to get the right answers, and that's where nerds show to advantage. Bill Gates will of course come to mind. Though notoriously lacking in social skills, he gets the right answers, at least as measured in revenue."

https://paulgraham.com/nerds.html

Graham basically argues that high school society is miserable because it's a zero-sum status competition. Real life is a little better because positive-sum interactions are possible. We move from a competitive PvP environment to a collaborative PvE one after high school.

I'm concerned that as we get wealthier, and it's less essential for us to cooperate with one another to meet our essential needs, our mode of interaction will shift back from positive-sum to zero-sum.

The US is one of the world's wealthiest countries. But we also have some of the world's most bitter politics. And within the US, the angriest people tend to be quite wealthy:

"Progressive Activists have strong ideological views, high levels of engagement with political issues, and the highest levels of education and socioeconomic status. Their own circumstances are secure. They feel safer than any group, which perhaps frees them to devote more attention to larger issues of social justice in their society. They have an outsized role in public debates, even though they comprise a small portion of the total population, about one in 12 Americans."

https://hiddentribes.us/profiles/

Similarly, you can see a lot of bitter, zero-sum status competition on social media.

I worry that post-scarcity will be a sort of high-school dystopia with endless petty status competition. It might be good to think about how this outcome could be averted in advance.

By the second paragraph, I was thinking "Is he going to discuss the Culture series"?

You neglected to mention that Gurgeh, the game playing protagonist in The Player of Games starts out the novel bored (he's run out of challenging opponents). His life only gets exciting and meaningful after he is recruited by Special Circumstances (the Culture's equivalent of Bill Donovan's WW2 Office of Strategic Services). HIs assignment: to bring down an evil civilization by beating its leaders at their hideously complex imperial game.