Why self-help books are terrible and wonderful

Some advice on advice

A great truth is a truth whose opposite is also a great truth.

—Niels Bohr

I am a sucker for books that tell me how to be a better person. When I was much younger, I read Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl, and they changed my life. Recent favorites include Tribe of Mentors, a compendium of good advice by Tim Ferriss; The Four Tendencies by Gretchen Rubin; Mating in Captivity by Esther Perel; and Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman (which doesn’t exactly fit in this category but is too good to leave out).

I love those sorts of books, even though, in a certain way, they are all terrible. They tell story after story where their advice works. Sometimes, the stories are about historical figures or celebrities; sometimes (when the books are written by coaches, consultants, or therapists) they are about clients or patients. Often the advice-givers tell stories about themselves—I used to suck, but then I did such-and-so, and now I’m awesome.

The problem with stories is that you can’t take them as evidence for general principles. They suggest that at least one person’s life was improved by, say, waking up at 5 AM and walking barefoot on the grass, engaging in mindfulness meditation, sleeping in a separate room from their partner, studying Stoic wisdom, never splitting the difference, getting to Inbox Zero, and living life each day as if it was their last. But we don’t know whether most people would find this advice useless or worse than useless. And, really, we don’t even know if this one person’s life was improved. Maybe they would have been better off if they slept in, split the difference, and lived each day as if they had years and years of life ahead of them.

This is what scientific research is for, you might think. Get 1000 people to read the Stoics for an hour a day, get another 1000 to read, say, Stephen King novels for the same hour (a control group), and then see who is better off at the end. A lot easier said than done—among other things, it’s not apparent just how to measure better-offness—but there is some promising research along these lines. In an earlier post, I talked about a recent article written by Dunigan Folk and Elizabeth Dunn (free to download here) that summarizes the best experimental research about what makes you happier and what doesn’t. Here is what they found:

Our review … points to the value of expressing gratitude, being more sociable, acting happy, and spending money on others. In contrast, we found surprisingly little support for many commonly recommended strategies for promoting happiness, including practicing meditation, doing random acts of kindness, or engaging in volunteer work. Most happiness research has focused on practices that individuals can add to their lives, but some recent studies provide hints that removing some of our daily habits could also improve happiness; specifically, individuals may benefit from giving up social media use for an extended period or buying themselves out of unpleasant daily tasks.

Even when interventions work, though, they are relatively weak—you need to test hundreds of subjects to see an effect.

You won’t find this sort of careful research discussed in these advice books. The best books avoid research altogether. The lesser ones cite studies to support their advice, and it’s inevitably cringe-worthy—random citations of crap experiments from twenty years ago that nobody should have ever taken seriously.

In addition to stories, there are aphorisms. So many aphorisms! I’m not complaining. Aphorisms are fun. In honor of these books, I led this post with one I like, from Niels Bohr. Another one I just read is from Benjamin Franklin.

“When testing to see how deep water is, never use two feet.”

And here’s one I talked about before, from the psychologist Daniel Kahneman:

“Nothing in life is as important as you think it is while you’re thinking about it.”

You wouldn't believe how often these authors contradict themselves. Ryan Holiday’s Discipline is Destiny has a chapter called “Ruling over the Body,” which tells the story of Lou Gehrig.

He played through fevers and migraines. He played through crippling back pain; pulled muscles; sprained ankles; and once, the day after being hit in the head by an eighty-mile-per-hour fastball, he suited up and played in Babe Ruth's hat, because the swelling made it impossible to put on his own.

For 2,130 consecutive games, Lou Gehrig played first base for the New York Yankees, a streak of physical stamina that stood for the next five-and-a-half decades. … Yet he never missed a game. Not because he was never injured or sick, but because he was an Iron Horse of a man who refused to quit, who pushed through pain and physical limits that others would have used as an excuse. At some point, Gehrig's hands were X-rayed, and stunned doctors found at least seventeen healed fractures. Over the course of his career, he'd broken nearly every one of his fingers—and it not only hadn't slowed him down, but he'd failed to say a word about it.

An Iron Horse of a man. Holiday sums up the moral here.

The truly dedicated are harder on themselves than any outside person could ever be. …

We owe it to ourselves, to our goals, to the game, to keep going. To keep pushing. To stay pure. To be tough.

To conquer our bodies before they conquer us.

What a great model for living! But read on, and you’ll get to a chapter called “Manage the Load,” where Holiday tells us how Gregg Popovich, the coach of the San Antonio Spurs, rested four of his best players during a nationally televised game.

[This] was shockingly controversial. The team wanted them to play. The fans were pissed and wanted refunds. The TV announcers were livid, and so were the channels that had paid for the broadcast rights. Other coaches complained, and athletes condemned him. The league's punishment was swift and costly.

But Popovich had the discipline to play a longer game—to strategically rest his athletes so they would have enough gas to make a run deep into the playoffs, and so they could have longer careers and continue to play at an elite level.

The moral here is clear.

To last, to be great, you have to understand how to rest. Not just rest, but relax, too, have fun too. (After all, what kind of success is it if you can never lay it down?)

The most surefire way to make yourself more fragile, to cut your career short, is to be undisciplined about rest and recovery, to push yourself too hard, too fast, to overtrain and to pursue the false economy of overwork.

Manage the load.

More great advice! But which piece of great advice should you follow? Should you rule over the body? Or should you manage the load?

It might sound like I’m criticizing Discipline is Destiny. I’m not. I don’t mind the contradiction. (Once again: A great truth is a truth whose opposite is also a great truth.) Actually, I think Holiday’s book is great—but you can only see its greatness when you appreciate the three things that these books do well.

1. Establishing an alliance

You’ve probably heard this: A woman complains to a man about a problem, and he responds by offering solutions. She’s annoyed. This is not what she wants; she was looking for support and engagement.

At least, that’s the cliche. I have no idea whether these really are typical male and female styles. But if we see these as two general approaches to problems, the best advice books are largely in the stereotypically female mode. They provide support and encouragement.

Other sorts of books don’t do this. They will blame your problems on your genes, original sin, or late-stage capitalism—forces you are powerless against. Many people in your life are similarly pessimistic: they will tell you that you’ll never change and that it’s no use trying. But Tim Ferris, Gretchen Rubin, and the bunch don’t believe this for a second. Your life is about to be transformed—just start reading!

In this regard, reading these books is similar to therapy (or, to put it differently, maybe reading them is a form of therapy.) A finding from clinical psychology is that just about all therapies work to some extent, regardless of the specific techniques that are used. One theory is that this positive effect arises from the bond that the client has with the therapist—what shrinks call the “therapeutic alliance.”. There is support; you’re dealing with a person who accepts you, who feels compassion for you, who encourages you, who guides you, who is on your side. And there’s hope. When you meet with a therapist, it is usually with some faith that this will work. You wouldn’t be there if you didn’t think it had some chance of success.

Replace “therapist” with “author of a self-help book,” and the point still holds.

2. Instilling a habit of reflection

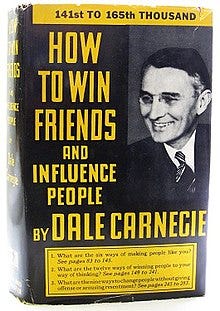

People often read books that bear on aspects of their lives that they think about a lot. You might have problems sleeping, so you’ll get a book on how to fall asleep; you might struggle with finishing your novel, so you’ll get a book on being a more productive writer. You might worry that you’re not winning friends and influencing people, so you go out and buy Dale Carnegie’s wonderful How to Win Friends and Influence People.

But we often get the most out of books that bear on parts of our lives we don’t think about at all. These books change us in a way that other books don’t. They instill a habit of reflection.

Take Never Split the Difference by Chris Voss, which is about negotiating. Before reading the book, I never considered negotiation, but now I do. I reflect on parts of my life that used to be on auto-pilot.

Or consider teaching. This might be surprising to hear, given that I’m a university professor, but for much of my career, I rarely did much thinking about what I did in the classroom. My energies went into research, writing, and advising; I just muddled through my lectures and seminars without giving them much thought. One day, and I forget why, I ended up picking up the book What the Best College Teachers Do by Ken Bain, and this got me to reflect on the teaching process, and I’ve been reflecting ever since.

Is all of this reflection good? Not always. If you’re expert at something, there’s a lot of research showing that reflecting on it—mulling it over, thinking about what you’re doing, going from automatic to manual—can really mess things up. A lot of this research is done with athletes, especially golfers, but the point is more general. (Some advice of my own: If you are a good sleeper, do not read books about insomnia.)

But for all of those other parts of your life where you’re just muddling through, it can be useful to reflect on what you’re doing and consciously monitor what works and what doesn’t. These books can help.

3. Providing advice

Sometimes, these books of advice actually have good advice.

It’s never in the generalities. I don’t mind being told to live life to the fullest, adopt a stoic attitude, or conquer my body before it conquers me. This sort of advice might cheer me up and might motivate me to reflect on my life. But it’s not usable in any sense—to use a business term, none of it is “actionable.”

The books I like the most get into the weeds. What I like about Tribe of Mentors, for instance, is that it’s full of specifics. Drink this kind of tea. Buy this backpack. Watch this YouTube video and do these stretching exercises.

Or take Chris Voss’ Never Split the Difference. I remember exactly one thing from this book, but it’s a good thing: When you have to name a price, don’t give a number; give a range.

Instead of saying, "I'm worth $110,000," Jerry might have said, "At top places like X Corp., people in this job get between $130,000 and $170,000."

The idea is clever. Rather than saying, “I usually get X for that sort of thing,” I now say, “I usually get between X and Y for that sort of thing.” Often, the people I say this to respond by offering me X. As Voss points out, when you give a range, people will go for the minimum, but that’s fine—they feel good about it because they think they got me on the cheap, and I feel good about it, too, because X is what I wanted in the first place.

Good books are full of these neat little tricks.

I was a manager at General Electric for a decade. We were prescribed self help books (7 Habits for example) and pop business management books (Good to Great). I came to loathe them, but read them as told - usually on airplane.

Good to Great the worst - the central message is that companies that go from Good to Great have an intelligent, humble, steadfast CEO at the helm - so listen to him. The book taught me one thing - that there is no easier way to make money than writing a trite book telling powerful, wealthy people they are wonderful and deserve all the fawning they receive and greater financial compensation. GE went broke a few years later and almost went under completely.

I don’t really have a comment, except that this is a really fantastic piece. One of your best!

I guess since I am commenting already, I’ll add that the control group of Stephen King readers should exclude On Writing, which is self-help adjacent (and excellent).

Actually, novels are full of moral instruction. Give the controls puzzle games.