Virtual Reality is a terrible empathy machine

And we don't know if books are any better

VR is cool. Many people have argued that it is going to transform education, therapy, marketing, fitness, porn, and, of course, video games.

I believe it. I have an Oculus Rift, and it’s loads of fun. Pistol Whip is an awesome first-person shooter and Beat Saber makes me sweat. There’s still a lot to work out—nobody likes wearing a heavy helmet—but the technology is getting better. I’ve heard great things about the Apple Vision Pro (pictured above) and I’m trying to think up a research idea that will give me an excuse to buy one or two for my lab.

Some people make the additional claim that we can use VR to become better people. The technology will help us appreciate the lives of those such as refugees, the homeless, and individuals with physical and mental impairments. As the entrepreneur Chris Milk puts it in his TED talk, VR is “the ultimate empathy machine.”

I disagree. The various versions of VR out there, high-tech and low-tech, are terrible empathy machines. After using them, you often end up with less of an understanding of other lives than you started with.

Charities love VR. In a New York City fundraiser by the International Rescue Committee, people lined up to use headsets that let them experience the physical environment of a refugee camp in Lebanon. NPR quotes the executive producer of the IRC: “We can't bring donors or people to the field, but we bring the field to [them.] That's what's so great about VR; that's what makes it, I think, such an important tool for charities."

The picture below is of visitors to a different refugee simulation, set up in Denmark, called “Forced From Home”:

You can do VR on the cheap. Another exhibit in Washington, set up by Médecins Sans Frontières, had participants climb onto rafts (on dry land) and go through a series of ordeals, having to give up their possessions one by one until they ended up, empty-handed, in front of faux refugee camps.

There have long been disability simulations, in which participants sit in wheelchairs, get blindfolded so they know what it’s like to lose their sight, or listen to intrusive sounds to simulate schizophrenia. There are age simulations—you can slip into an “Age Suit” and experience the aches and pains of an 85-year-old. And there are pregnancy simulations; if you buy the “Empathy Belly”, you get to experience all this:

Whee! The company boasts:

With over 20,000 Empathy Bellies® in use worldwide, teachers continue to praise this unique resource for contributing to the recent decline in teen pregnancies.

So what’s not to like?

Well, start by considering something strange about these simulations: They are fun. If I were setting up a fundraiser, I’d be tempted to use VR to bring people to my event. I’d love to try out the Age Suit and the Empathy Belly.

Isn’t that odd? It’s not fun to be a refugee. If there was a machine that could make me really experience what it would be like to be in that situation—as opposed to experiencing walking around a refugee camp—I might choose to plug myself in, but it would be a difficult decision. I might do it out of curiosity or obligation, but not for enjoyment.

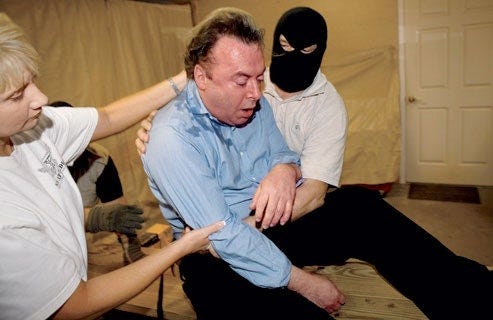

One difference between simulation and reality has to do with control. During the debates over the interrogation practices of the United States during the Iraq war, Christopher Hitchens got military personnel to waterboard him, just to see what it was like.

He said it was awful. His piece was titled: Believe Me, It’s Torture, and his description—Hitch was a superb writer—is vivid and disturbing. He had two rounds; here is how the first ended:

Unable to determine whether I was breathing in or out, and flooded more with sheer panic than with mere water, I triggered the pre-arranged signal and felt the unbelievable relief of being pulled upright and having the soaking and stifling layers pulled off me.

There was, of course, a pre-arranged signal to make the torment stop. And because of this, his experience fell far short of how terrible waterboarding is, because when it happens in the real world, the people doing it don’t stop when you ask them to.

The feeling of being water-boarded is objectively terrible, but in many cases, this sort of control, along with the knowledge that you’re actually safe, can transform unpleasant experiences into fun. This is why we pay to play war games and have paintball battles, get frightened by shrieking maniacs in a haunted house, or engage in certain masochistic sexual activities. Things are very different when there is no safe word.

(This point was missed by Donald H. Rumsfeld, who, when told that prisoners in Guantanamo had to stand for many hours a day, responded that he himself had a standing desk and was also standing for many hours a day. But of course, he could sit down whenever he wanted.)

Then there is duration. It’s not difficult to try out certain short-term experiences, such as dealing with a crying baby for a few minutes, sitting alone in a closet, or having strangers gawk at you on the street. But you can’t extrapolate from these to learn what it’s like to be a single parent, a prisoner in solitary confinement, or a movie star. You can’t take an experience of minutes and hours and generalize it to months and years. Just as going into town and leaving your credit cards behind won’t let you appreciate what it is to be poor, playing at being a refugee won’t let you appreciate what it’s like to be a refugee.

So too with the Empathy Belly and the Age Suit. You know the thing about being pregnant? It lasts for months. You know the thing about being old? Well, if you’re lucky, it lasts for years—and tends to get worse over time.

Duration matters. Some experiences are fine in the short-term, but wear you down over time. Solitary confinement is an obvious example here. Or consider subtle forms of sexual and racial discrimination—certain seemingly minor attacks on one’s dignity are easy to shrug off in any single instance, but if they are repeated and relentless, they just build on you.

Other experiences are awful in the short term but improve over time; we habituate and adapt. VR is short-term, so it can’t capture this.

This is the problem with disability simulations. In a scathing review of the literature, disability activist Arielle Michal Silverman points out that these simulations

give the mistaken impression that the entirety of being disabled is marked by loss, frustration, and incompetence.

One study, for instance, asked subjects to wear blindfolds for a short period. When the blindfolds were removed, the subjects

described their experience as being very difficult, frustrating, confusing, and frightening. In fact, a few students spontaneously uttered remarks such as ‘thank God I’m not blind’ upon removing the blindfold. The students also projected their negative experiences onto blind people. Compared with control students, blindfolded students estimated that blind people experience more fear, anger, confusion, and distress on a daily basis.

And they were wrong. Blind people turn out to be pretty much as happy as sighted people. This is in large part because they adapt to their blindness. Silverman points out that, at best, disability simulations offer the experience of becoming blind, becoming paralyzed, and so on.

I’ve often been struck by how arrogant we can be about our capacity for empathy, by how quick we are to say “I know just how you feel”.

Sometimes we may be right, particularly when we are talking to people who are similar to us and have had the same experiences. If a professor in my department tells me how upset she is that a lecture went poorly, I can sort of get it, because I’m a professor too and I’ve also had lectures that went poorly. I have slammed my hand in a car door, fallen in love, watched my children being born, and spent several hours building a cabinet I bought from IKEA—and so if you have had these experiences, maybe it’s reasonable for me to say “I know just how you feel.”

But in general, we are nowhere near as good at empathy as we think we are. The psychologist Nicholas Epley discusses experiments in which people were asked to judge the thoughts of strangers. These included asking speed daters to identify others who wanted to date them, asking job candidates how impressed their interviewers were with them, and asking a range of people whether or not someone was lying to them. People are often highly confident in their ability to make such judgments, but their attempts are typically barely better than chance. Other studies find that people who are instructed to take the perspectives of others tend to do worse, not better, at judging their thoughts and emotions.

It gets worse when the experiences are unfamiliar. The philosopher Laurie Paul argues that it’s impossible to fully appreciate what it would be like to have certain deeply significant and transformative experiences, such as becoming a parent, changing your religion, or fighting a war. There’s not enough common ground with the life you’ve had so far. The same lack of access applies to our understanding of others. If I can’t know what it would be like for me to fight in a war, how can I expect to understand what it was like for someone else to have fought in a war? If I can’t understand what it would be like to become a refugee, how can I know what it’s like for someone else to be a refugee?

One approach is to go ahead and have the experience. Some have chronicled their attempts to take on other identities for long periods, like Norah Vincent in Self-Made Man, a memoir of how she posed as a man, or John Howard Griffin in Black Like Me, in which Griffin, a white man, recounts his experience living disguised as a black man in the segregated Deep South of the 1950s.

It’s unclear how successful such experiments are, but at least they are serious attempts to appreciate what it’s like to be another person, relinquishing control, taking real risks, and putting in enough time to get habituated to the experience. To think that you can even get close by putting on a helmet for 30 minutes or walking around with a blindfold for an hour is arrogant and foolish.

We should be more humble, particularly when it comes to people who are the victims of injustice. Instead of assuming that we can know what it is like to be them, we can focus more on listening to what they have to say. This isn’t perfect — people sometimes lie, or are confused, or deluded — but it’s by far the best method of figuring out the needs, desires, and histories of people who are different from us. It also shows more respect than a clumsy attempt to get into their skins. In this regard, I agree with the essayist Leslie Jamison, who describes empathy as “perched precariously between gift and invasion.”

CODA:

Some of this post draws from articles I wrote for The Atlantic and The New York Times a few years ago. I ended my original Atlantic article with this:

Fortunately, there is a better version of VR that avoids some of these problems. Affordable, durable, and small enough to hold in one hand, these devices allow you to simulate not only the physical environment of individuals, but also their psychological experiences, and can do this for multiple people, moving forward and backward in time. They enable you to experience the most private experiences of others, both by triggering your own memories and by extending your imagination in radical ways.

These “empathy machines” are books, of course—as in novels and journalism and autobiography. When it comes to simulating physical experiences, they are not as powerful as certain alternatives. (If you want to know what it feels like to fall into a freezing lake, don’t open up a book; put a bag of ice into your bathtub and hop in.) And it might well be that language offers us a pale imitation of what another consciousness is like, especially when it comes to people whose experiences and beliefs are radically different from our own.

But when it comes to understanding the lives of others, nothing else comes close.

And, in my New York Times article, I wrote this:

None of this is to say that the project of experiencing the lives of others should be abandoned. Under the right circumstances, we might have some limited success — I’d like to believe that novels and memoirs have given me some appreciation of what it’s like to be an autistic teenager, a geisha or a black boy growing up in the South.

I was careful to hedge my claims—”it may be that language offers us a pale imitation”, “some limited success”. But maybe I shouldn’t have made these claims about the power of literature in the first place.

Right now, I’m reading some old Dennis Lehane novels (starting with A Drink Before the War) where the narrator is Patrick Kenzie, a wise-cracking Private Investigator from a tough neighborhood in Boston. But am I really coming to know what it’s like to be a wise-cracking Private Investigator from a tough neighborhood in Boston? When I wrote the NYT piece, did I really have some appreciation of “what it’s like to be an autistic teenager, a geisha, or a black boy growing up in the South”?

Maybe; maybe not. Novels, memoirs, and the like often give us the feeling of being in the shoes of other people. Whether they actually give us an understanding of the lives of others is a question we don’t know the answer to.

Can’t agree more. And there’s nothing more alienating than a thoughtless “I know just how you feel”.

>how arrogant we can be about our capacity for empathy, by how quick we are to say “I know just how you feel”.

This is really important. I was well into adulthood when I realized how terrible it was to say that. Sorry to everyone I said this to in the past.