Three Productivity Tips For The Restless

(It’s the middle of August and I’m on a family vacation—and so I’m taking the opportunity to re-release a post from the start of 2024, with just a few minor edits. It’s one of my favorites, and I hope you like it.)

This is my most clickbait title ever, sorry.

If it were by someone else, I’d certainly click on it. I love advice on how to be more productive. When I meet a writer or scholar I respect, I struggle to resist the temptation to ask “What time of day do you work?” and “Any software you recommend?”

There’s something so interesting about the daily routines of successful creative people. In Peter Kramer’s superb biography, he describes Sigmund Freud’s typical day.

At home, Freud’s routine admits of few variants. Freud rises at seven and sees patients starting at eight. Sessions last fifty-five minutes, with five minutes between for tea. Freud takes no notes. The first set of sessions ends at one. At five past the hour, Freud joins his family, already seated, for the midday meal. After lunch, he walks in the city, often dropping off a manuscript. The cigar shop is on the route. Scrupulous about his appearance, Freud stops daily to have his beard barbered. Antiquities are his passion. Every other week, a dealer brings him objects for inspection. At three, Freud offers consultations to patients without appointments. At four, psychoanalytic hours resume. Dinner with the family is at seven, followed again by a walk, sometimes with Martha or a child. Then comes more office time, for correspondence. Serious writing—books and articles—begins at eleven P.M. and ends at two. Freud composes fluently. He does not revise, but discards unsatisfactory drafts. When a book is finished, he starts on the next. He falls asleep when his head hits the pillow and wakens spontaneously five hours later.

Or this, from Jay Parini’s essay “On Being Prolific”, on the routine of Anthony Trollope.

(In his essay, Parini recounts an old story about the literary critic, Harold Bloom. Bloom was famously prolific, and the story goes that a graduate student once phoned Bloom and his wife answered and said: “I’m sorry, he can’t talk—he’s writing a book.” The student responded: “That’s all right. I’ll wait.")

Or this, from a New Yorker profile of Joyce Carol Oates:

The first time I met Oates, at a restaurant near Princeton University, where she has taught since 1978, she had just returned from a trip to Scandinavia. She is eighty-five and very slim and agile, with perfect posture. She shows almost no signs of physical frailty. On her trip, after spending the days touring and giving interviews, she worked on her next novel in her hotel room every night, from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m.

I regularly read the series that Lifehacker used to put out called “How I Work”, like this one with Charles Duhigg. I’m a fan of productivity gurus, like Tim Ferris and Cal Newport, as well as the anti-productivity guru Oliver Burkeman, who wrote the wonderful book Four Thousand Weeks.

In a different mode, I’m reassured whenever I learn that people I admire have their own struggles with productivity. Oates is the Ideal Me; Franz Kafka, in the excerpt from his diaries at the top of this post, is more like the Actual Me.

Or check this out, from Ludwig Wittgenstein:

Here’s Charles Darwin writing to his friend Charles Lyell in 1861, and, man, I know the feeling:

I am very poorly today & very stupid & hate everybody & everything.

So now I’m going to step in with my own suggestions. Immediately I’m at a disadvantage. So much of the advice I’ve seen from other people revolves around the idea of an intense three to four-hour period of writing. Freud and Oates do theirs late at night; Trollope did his in the early morning—and he cautioned other writers not to work longer than he does.

All those I think of as literary men will agree with me that three hours a day will produce as much as a man ought to write.

Cal Newport adds an hour, suggesting that you should stop working at around four hours. More time isn’t worth it, he tells us. The quality will drop too much.

All of these writers are assuming that the problem has to do with stopping. This has never been an issue for me! I’ve always found the difficulty is, first, starting, and then, keeping going.

I can only remember one time when I wrote for over three hours in a single day. This was when I was up against a deadline for a grant, and I had to intersperse the writing with other activities, including going for a walk, checking my email, meeting a friend for lunch, and re-watching an episode of Scrubs. Three to four hours straight? If there was a gun to my head, I could (probably?) do it, but under more normal circumstances, one hour is my limit, and I sometimes don’t make it that far.

If this seems pathetic to you, you might want to stop reading at this point. But maybe you’re a little bit like this too? If so, these tips might be of interest.

1. Work every morning, right when you wake up

Every morning my plan is to wake up, make coffee (there’s a Nespresso Vertuo machine in my study, all ready to go; I just hit the button), and sit at the computer. The night before, I would have set the desktop up to make starting as frictionless as possible: The files for whatever I’m working on are open; everything else is shut down.

I put on a timer and try to write for an hour. For the tools I use during this hour, see Three Writing Tools I Love.

I suggest doing this, every morning.

(I’ll be assuming throughout that the project to be done is writing, but it could be anything difficult and important and done at a desk, such as data analysis, film editing, or financial planning.)

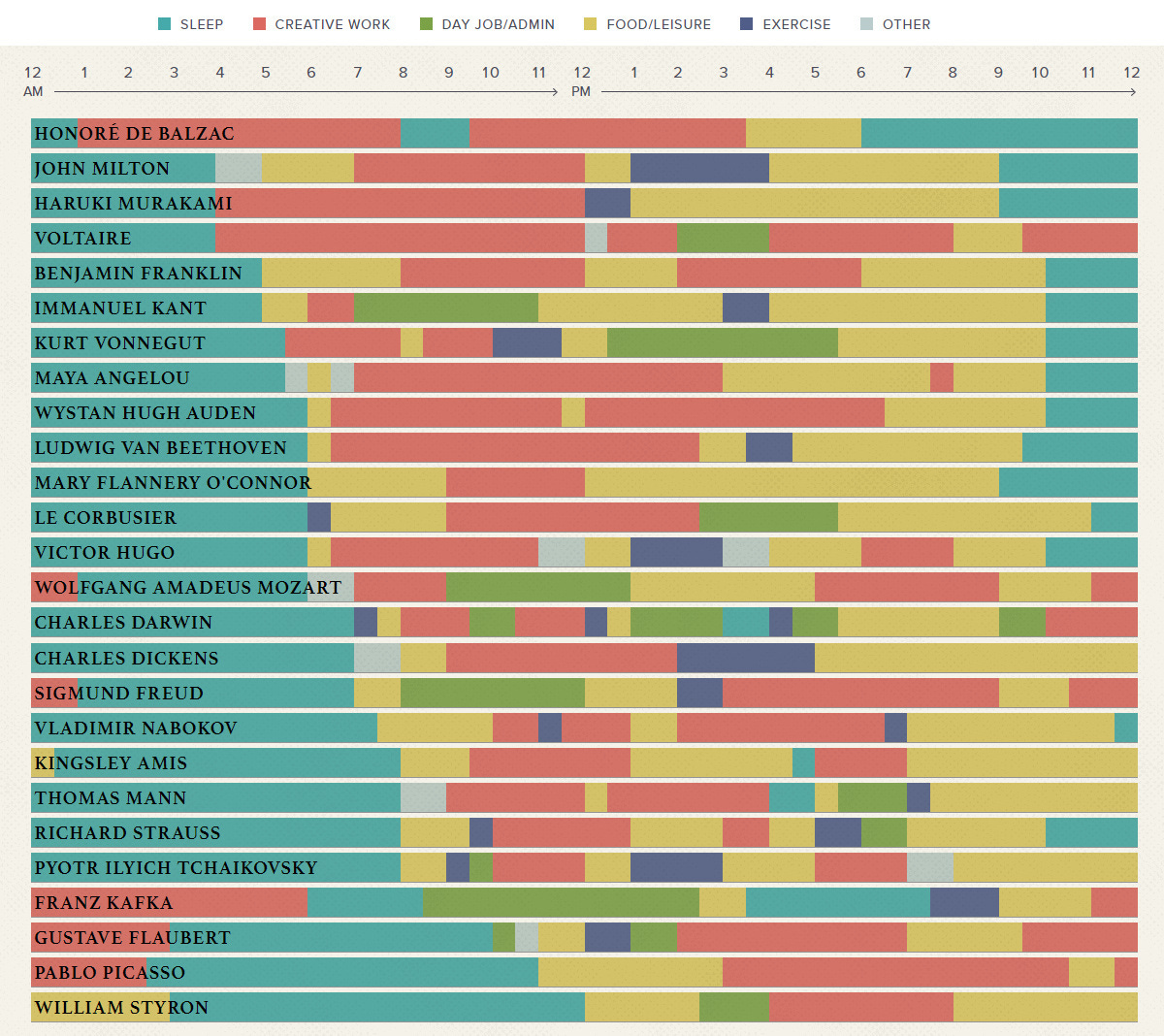

This is pretty typical advice. It’s what other people will tell you, and other people will tell you this because it’s a standard practice for productive people (though they usually do more than an hour.) There’s a book called Daily Rituals which is about the schedules of the Greats, and it includes a useful graph summarizing these schedules.

One shouldn’t take this as more than suggestive. Maybe the graph would look different if 25 different creative people were profiled. But it rings true for me, and I draw three conclusions from it.

First, productive people usually have daily routines. In an interview (sorry, I forget where I saw this) the author of Daily Routines said that he first chose the people and then wrote about them, so it’s not that he excluded anyone whose life couldn’t neatly fit into this sort of graph. Still, this isn’t inevitable; I know productive people who work more haphazardly and get big projects done in sustained multi-day bouts.

Second, almost all of these geniuses work for longer than I do—except for that slacker Immanuel Kant.

Third, the most common work time is in the morning—the graph has a lot of red between 7 and 10 AM. There are real advantages to morning work:

This is when many people are psychologically most ready for creative work. The time after waking up is often associated with the optimal combination of high engagement and low antsiness.

The world impinges less. You can write before your job starts, before chores have to be done, and before people expect things from you. If you have young children, you can wake up before they do. (Avoiding external distractions and responsibilities is also an advantage of the very different schedule that Freud and others have—writing very late at night).

Related to this, if you commit to doing something first thing in the morning, you are most likely to get it done. Commitments for later in the day can get derailed—a friend drops by, there is a crisis at work, and so on.

So that’s the first tip, but I’ll add that there are all sorts of reasons why this might not be good advice for you. We’ve already seen that some people work best late at night. (There might be an age thing going on—I only became a morning guy in my 30s and I know others who shifted at about the same age.)

Daniel Pink, in his book, When, proposes that mornings and evenings are peak times for most people. Here are the results from a Science paper that looked at half a billion tweets, analyzing them for how positive or negative they were, and then looking at the effects of time of day.

Summarizing the results from several studies, Pink writes

In short, our moods and performance oscillate during the day. For most of us, mood follows a common pattern: a peak, a trough, and a rebound. And that helps shape a dual pattern of performance. In the mornings, during the peak, most of us excel at … analytic work that requires sharpness, vigilance, and focus. Later in the day, during the recovery, most of us do better on ... insight work that requires less inhibition and resolve. (Midday troughs are good for very little) … Our capacities open and close according to a clock we don’t control.

Afternoons suck. But, as Pink later notes, there are exceptions. Some people start their days in a haze, good only for Wordle and Crosswordle; it takes about a couple of hours for their focus and energy to hit the right point, and they do their best work in the early afternoon. Your Mileage May Vary.

Also, mornings pose challenges for some. Perhaps there are early obligations you can’t get out of, such as caring for children or animals. Maybe you start your job early in the morning. You could always wake up earlier, but sleep is important, and not everyone is suited for one of those crazy going-to-bed-at-9PM-waking-at-5AM schedules.

Finally, mornings may be the best time for you, but there’s something more important for you to do during that period. A while ago, when I was running regularly, I recognized that while it’s great to write early in the morning, it’s also great to get my run in early in the morning—for some of the same reasons. I chose to prioritize my running.

Does it have to be an hour? Absolutely not. That’s just the time that works for me. If you’re a Trollope-type, you can go for much more. Less is also good. Many of us lack Sitzfleisch—a wonderful German word that means “sitting flesh” and refers to the ability to sit and work for long periods. Some of our bums are more suited for shorter periods of writing.

Almost fifty years ago, Virginia Valian wrote a terrific essay called Learning to Work, describing how she set up a plan to write her dissertation. She figured she’d work a set amount of time each day.

Finally, some thoughts on the “every morning” part. There are advantages to consistent everyday work. Most of all, stuff accumulates. Trollope wrote 2500 words per morning. At this impressive pace, a month of work gives you 75,000 words, which is a perfectly respectable novel or work of non-fiction, or several chapters and articles. Or, more realistically, it’s a very rough and preliminary version of a book or bunch of chapters and articles.

Now this is a crazy pace. But suppose you wrote for fifteen minutes a day, producing 200 words. That’s about 73,000 words per year—which is still mighty impressive. Call this a rough draft; spend the next year cleaning it up, and then you have a book.

Also, an everyday schedule is just simpler. Valian again:

Do I write every morning? Sadly, no. I might have to get an early flight. I might be at a conference and have to go to a talk or meeting the minute I wake up. (Unless you’re Joyce Carol Oates, travel messes with your productivity.) I might have some pressing deadline that I need to spend all my time on (though even here, I try to eke out 10 or 20 minutes of writing).

And sometimes I sleep poorly, and I just goddamn don’t feel like writing, and instead spend that hour in bed, staring at my phone. These things happen. I try to be philosophical about it and tell myself I’ll get back to the routine tomorrow. And I usually do.

2. Then, six-minute bursts

Here’s where it gets weird. Suppose I have two hours of uninterrupted time and a lot to do. It’s not the morning anymore, and deep and focused work is beyond me.

The normal piece of advice here, maybe too obvious to even count as advice, is to work on one task, perhaps the most important one, and make as much progress as you can. When you finish the task, move to the next.

This is not what I do. I have a timer on my computer and set it for six minutes (sometimes four minutes, sometimes eight, but usually six). Then I start to work on something. When the timer goes off, I reset it and switch to something else. After about 5-10 activities, I’ll circle back. Usually one of the things on my list will be fun, and at least one of them will involve getting up from the desk. Here’s a typical list of 6-minute activities.

reading a scientific article

answering email

putting away laundry (If I’m working at home, obviously)

doing the New York Times Spelling Bee

writing reference letters

editing a paper that I’m writing with some colleagues

making a dentist appointment

looking at submissions for the journal I’m the editor of

If I finish something before the six minutes (maybe it took two minutes to make the dentist appointment), I just move to the next.

Advantages? You won’t get bored. Your workday will include rewarding periods because some of the tasks are fun. You’ll make progress on things you’re avoiding—like, for me, making a dentist appointment—because 6 minutes just isn’t that much, and, however agonizing the task, you know it will be over soon.

Disadvantages? Well, some people find this insane. The idea of quickly switching from task to task is repellent to them—the worst advice ever. The transaction costs are too high; it’s just too difficult to suddenly stop one thing and start another. If this is your reaction, maybe this isn’t for you. Once again, YMMV.

But it does work for some people. I mentioned this on a podcast, and a week later, I got a sort of celebrity endorsement from Oliver Burkeman, in his newsletter The Imperfectionist.

Splendidly nerdy! I can live with that.

It would be dishonest for me to stop with this quote, though, because Burkeman goes on to tell his readers not to take my advice, or any advice, too seriously.

For more from Burkeman see here.

I agree with him, both for his specific claim that this six-minute method is unsuited for work that requires deep focus (at least for most people), and his more general advice on how to think about productivity advice. And this brings me to my third tip.

3. Know Thyself

The third piece of advice is actually meta-advice—advice on how to think about advice.

There are no strategies that work for everyone. My first tip was to work in the mornings, and I do think it’s good advice, but if you look again at the graph—and the people around you—you’ll see that creative people work at different times, with evenings being a popular option. Many of the pros work for stretches of three to four hours; I suggested one hour; and Valian says to begin with fifteen minutes. Some work every day; some only on weekdays; and others when the spirit moves them.

My second tip of working in short bursts is geared towards those like me, who find it hard to focus on one thing for too long (yes, the phrase “adult ADHD” has been tossed my way). But, as I mentioned earlier, some people are the perfect opposites and do their best work by putting aside long periods of sustained concentration.

The point here is that there are a lot of ways to do this well. There’s a temptation to look at what successful people do and try to change yourself to fit the contours of their lives. I believe that once you’re an adult, this sort of transformation—for a writing schedule, or anything else—is a mug’s game. Best to invert the process: Accept yourself as you are, and try to establish routines that fit best with your strengths, weaknesses, ambitions, and proclivities. Seek out techniques that match how you are, try out those, and if they don’t work, try others. (Productivity advice is a lot like parenting advice—if you look hard enough, you’ll find someone who will tell you what you want to hear.)

For this to work, you have to know the answers to some questions. What time of day do you work best? What about particular kinds of work—is there a good time for what Daniel Pink calls “analytic work” and a different good time for what he calls “insight work”? How long can you work at a stretch before the quality drops? What’s your optimal dosage of stimulants? Some take nothing; some like a nice cuppa tea. For me, a mug of strong coffee when I start is essential, but a second cup makes me uncomfortably twitchy. But maybe I’m missing out on the powers of caffeine. Parini on Balzac:

Is your nighttime work improved by beer, whiskey, or a joint? (Mine isn’t, but some benefit from the buzz, and I’ll spare you tales of great masterpieces written by the blotto.) Silence, music, or a bustling cafe? Sitting, standing, treadmill, or lying in bed? Naked, sweatpants, or dressed as if you’re going for a job interview.

Important: The questions here aren’t about what you like; they are about the circumstances that give rise to your best work. There’s a big difference. For many years when I lived in New Haven, I would leave my office on many afternoons and walk to a cigar bar called The Owl Shop, (the only business in New Haven where indoor smoking is permitted).

I’d light up a cigar, order a coffee (unless it was late, in which case I might move to beer or whiskey), sit at one of the overstuffed leather chairs, and take out my laptop.

I loved The Owl Shop and would tell people that it was my favorite place to work. But really it was my favorite place to be. Sure, I wrote a few emails when I was there, and maybe glanced at a student paper, but I was too relaxed to get into a groove, and the people around me were just too damn interesting. I once listened to two older men sit at the bar and, though they were using carefully coded language, it was clear they were planning some sort of crime. I once watched a giggling woman approach an attractive young couple sitting on a sofa close to me and invite them to have a foursome with her and her boyfriend—he sat quite a ways back, waving shyly. The couple politely said no, the woman walked away, and then the couple, clearly charged up by the encounter, started to passionately kiss.

Who can write under these circumstances? Who would want to?

Sorry for the digression; I missed that place and wanted to reminisce a bit. But the point of this example is that Knowing Thyself is not the task of knowing what you want; it’s the much harder problem of figuring out the conditions under which you are most productive. For me, The Owl Shop was a great place to relax; not so good for work.

Figure all of this out, then build your work schedule around it. Don’t change yourself; shape the world so that it best matches the way you are. I think it is good advice for productivity, and possibly good advice for everything else.

Good luck!

I've said it before and I'll say it again: you are my favourite productivity guru, Paul. I think because you aren't a productivity guru.

I was just thinking about that writers work habits chart last night and here you are posting it again!

Here for the clickbait - but what a great post. Thank you for resharing it. This is an obsession of mine, so much so I wrote a whole book on it and Oliver Burkeman was kind enough to write the foreword. He is so very wise. As is Mason Currey author of Daily Rituals who you also quote - do you follow him on Substack, his subtle maneuvers is packed full of wonderful writing quirks and humour: https://masoncurrey.substack.com/